Affected areas: Kancheepuram, Cuddalore, Nagapattinam, Villupuram, Velankanni, Nagore. And Karaikal in Pondicherry.

The Big Churn

All along the coast, it's those who live by the sea that have succumbed to it. The fishing community is in despair. <a >Updates</a>

Worst hit: Nagapattinam alone could account for 20,000 deaths.

Velankanni: The Catholic shrine town had thousands of devotees visiting for Christmas. Many are on the missing list.

Earth-shattering isn’t just a figure of speech anymore. As the earth wobbled on its axis on December 26, India’s southern coastline received dire whip lashings from the sea. On the Tamil Nadu coast, by the time the tidal waves settled, the sea had advanced by 75-100 metres. Geologists say maps may have to be redrawn now. In Nagapattinam, the worst-hit district in the state, people walk around as if they have totally lost their moorings. On the Velankanni beach, a fibre-glass boat bearing a Nagore address—with the owner’s cell number (9842377611) painted on it—has washed ashore. Nagore is some 20 km from Velankanni. Bodies from Velankanni have been swept as far away as Vedaranyam and Kodiyakarai, 40 km away. The impact of the tsunami has been such that bodies, boats and trawlers were flung miles away from their original location.

As always, when the sea rages, the fishing community takes the brunt of it all. But for the unlucky morning walker or tourist, 90 per cent of the 25,000 casualties in Tamil Nadu and Pondicherry are fisherfolk. Over 6.5 lakh members of the community have been either affected or displaced. K. Murugan, a fisherman in the Keechankuppam hamlet of Nagapattinam, says: "We’re afraid of the sea. I have seen storms and cyclones but nothing like this."

This is the state of mind among fisherfolk in general. Some 2,500 have died in Keechankuppam alone, where tsunami-rammed trawlers lie in entangled heaps. Says pmk leader and MP from Pondicherry, M. Ramadoss, who belongs to the fishing community, "Usually, they are keen to go back to the sea even two days after a cyclone. But for the first time, I saw them say they don’t want to go anywhere near the sea. Besides all the medical aid and relief pouring in, the fishing community needs psychological counselling. They are still in a state of shock." In Tamil Nadu, the community is estimated to account for 5 per cent of the population.

The tsunami and its impact are also bad news for the state’s economy. With an annual production of 4 lakh tonnes of marine products—3.75 lakh tonnes catering to the export market—it generates business worth over Rs 2,300 crore. After the killer waves, close to 7,000 mechanised boats and 30,000 country boats have been fully or partially damaged. About 32,000 nets have been destroyed. Says Ramadoss, "If a family has lost one catamaran and one net, Rs 25,000 compensation will be required at the least. Those who had a small fibre boat will need Rs 2.5 lakh to recoup, and those who lost large boats and trawlers up to Rs 18 lakh." He says, in the long term, the government will have to consider the macro picture.

Nature is fickle but human beings are no better. In Cuddalore district, Sonankuppam and Singarathoppu are adjoining fishing hamlets, and traditionally at loggerheads. On December 26, at about 9.30 am with people crying "run for your life", some men went to get their spears and knives thinking "the enemies" from the neighbouring village were attacking. By the time they realised it was the deluge, it was too late. Today, nothing remains of the two hamlets.

A. Kadiravel, a fisherman and our guide in Sonankuppam, points to a contorted net and asks us: "Do you know how much it costs?" We don’t. "That web of blue plastic with red bobs clinging to it costs Rs 80,000." Murali, a fisherman of Devanampatnam, Cuddalore, is rather angry with the rest of society. "Why have we lost so much in lives and property? And why is no one really bothered? It isn’t rotten food packets and clothes that we need.We want our life back.We need our boats and nets and homes." Murali feels the fisherfolk have been forced to living on society’s fringes. "In the name of development and beautification, we have been pushed closer and closer to the sea."

In Keechankuppam and Pattinacherry, huts are located just 100 metres from the high-tide shore.The Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) rules recommend a minimum of 500 metres distance from the shore in rural areas. Ravikumar, Pondicherry-based writer and activist, is hoping the disaster will offer an opportunity for the rest of society to try and understand the life of the fisherfolk. "I am trying to get leading Tamil writers to issue a statement about the need to sensitise the rest of society to the lives of fisherfolk. Their lives are confined to the seashore and they are demonised by the rest of society. This has to be tackled. We know so little about their travails."

Many fishermen reason that the relief work here has been tardy because "we don’t live in big buildings like those who died in the Gujarat quake. We are largely an invisible people. We lead perishable lives and own perishable property. There’s little that mainstream society knows about us". According to another member of the community, it’s because "we do not have relatives among ias officers, police and ministers. We rarely have anything more than middle schools located in our areas. We are a dispensable people. We wouldn’t have been facing such a terrible fate if people belonging to other castes and communities had taken to fishing as an occupation."

So, could this be a reason why the Centre has still not declared the tsunami a national calamity? While the Bhuj quake quickly qualified for that status. The tsunami is merely ‘described’ as a national calamity by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who stopped short of officially declaring it as one. It may appear to be a case of quibbling, but an official ‘national calamity’ implies far greater aid from the Centre.

Equally strange is the fact that India has refused generous offers of aid from countries like Russia, the US, Israel and Japan. According to a government official, "Right now, we not only have adequate resources but have gone out and mounted a huge relief effort for Sri Lanka and Maldives. We could not have done this if we were facing a problem in Indian relief operations." This means that while the UN Disaster Assessment and Coordination teams have reached Thailand, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Maldives, India remains out of bounds for them.

Such a ‘United Nations-free’ policy also leads to obfuscation of the reality of death. In several parts of Nagapattinam, even on the fourth day after the disaster, decomposed bodies were being burnt. Hundreds of them are still to be recovered. Bodies have even been found hanging from treetops. These rarely enter the official register.

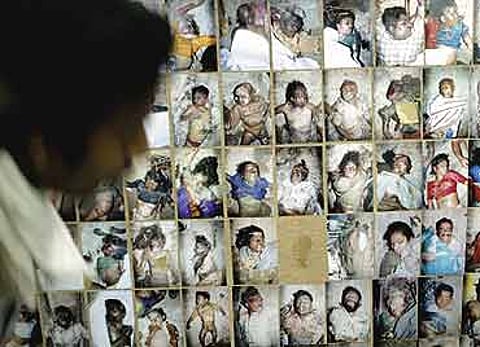

In Velankanni, the Catholic pilgrim centre where about 25,000 people had congregated for Christmas, unofficial estimates peg the dead at close to 3,000. The government’s figure for Velankanni is less than 1,000. For all of Nagapattinam, as of December 29, the government estimate remained a conservative 4,500. Sneha, an ngo based there, conducted a survey of 50 coastal villages in Nagapattinam and Karaikal and arrived at a figure of 12,300 dead as on December 29. Of these, more than 50 per cent are children. Women account for 3,600. These figures exclude the dead among the tourists visiting Velankanni.

According to Sneha, hundreds of bodies are lying decomposed in the interior villages of Tarangambadi and Sirkazhi taluqs. In Pattinacherry, near Nagore, hundreds of bodies are being burnt as and where they are found. The toll in this village alone is pegged at 2,000 by survivors.Says Sivakumar, a survivor, "In neighbouring Silladinagar, some 750 bodies have been recovered so far and 500 more are feared dead." Given the predominant loss of children, it looks like half a generation may have been wiped out. "It indicates a very bleak future for the fishing community. The loss of manpower cannot be accounted for by any amount of compensation," says Ramadoss.

Outside the Basilica of Our Lady of Good Health at Velankanni, a black Santro bearing a Chennai registration number stands locked and unclaimed five days after the tsunami. Everyone suspects the family which came in the car has died on the beachfront. K.A. Joseph, a shopkeeper at Velankanni, recounts many tragic tales. "I saw a bus from Kerala come with 55 people. When they left that evening, the bus had only 25."

The official estimate includes only "identified bodies". But most bodies recovered remain unidentifiable. Says Jesurathinam of the Coastal Action Network, "The village administrative officers refuse to register a death without seeing a corpse. Five days after the incident, when survivors treat their lost and missing kin as dead, this must be accepted and compensation given." Given that bodies have been swept away far from their points of origin, it’s a moot point that survivors may not always find the bodies of their relatives.

There are, of course, some coastal villages that have survived the tsunami. Koolaiyar and Chinnakottaimedu in Nagapattinam have reported only 20-25 deaths and minimal property damage. Jesurathinam says the reasons are environmental. "These two places have rich sand dunes which act as barriers against water inflow. In Nambiar Nagar, a small hut located behind a dune has remained intact. However, on the Nagapattinam town beach, four years ago the municipality cleared all the sand dunes in the name of beautification. We have paid the price now."

Another natural barrier that could have impeded the tsunami is the presence of mangroves. The Pichavaram area in Thiruvarur district has hence remained intact with no loss to life or property. Casuarina plantations and dense coconut groves have also acted as barriers in several places. "There’s an environmental lesson to be learnt here," says Jesurathinam.

Among all this, another tragedy is unfolding in the relief camps where sanitary conditions leave much to be desired and the rations provided is sub-standard. Says K. Palanisamy, at a relief camp in Nagore, "We were served stale tamarind rice this morning. Our children ate it and vomited. We can’t keep eating dry bread. Will our children who have survived die too?" Right now, all that the government and relief agencies can do is to stop that from happening.

Tags