The Big Budget Flop

Successive regimes have reduced a prudent state to a big borrower

Pawar, presenting his maiden budget, told the legislature that “the state would have got Rs 100 crore by way of VAT but we decided to waive it”. He had indeed made producers, who do not mind cancelling film shoots costing Rs 50 lakh a day, very happy. Rs 100 crore in VAT from the world’s largest and thriving film industry would easily have offset the shortfall in Pawar’s allocation to agriculture, or equalled the increased allocation for public works, or given him half the increased allocation to health and family welfare. So, as wealthy film producers rub their hands in glee, Pawar and his team of finance ministry officials will scrounge around to make good the shortfall entailed by the waiver.

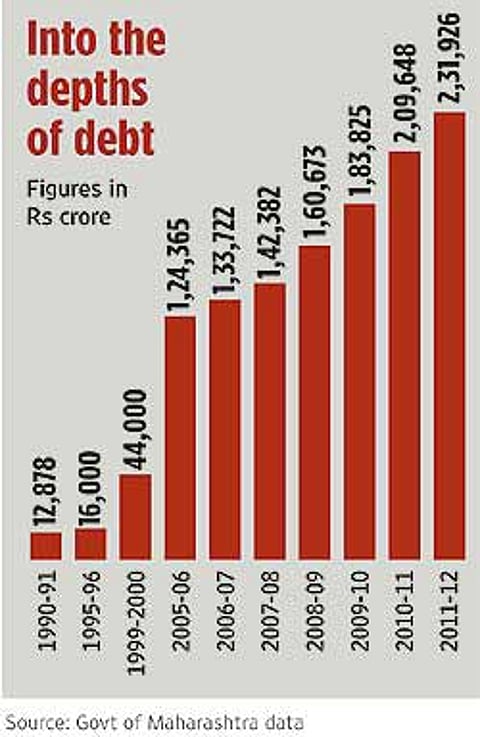

This might have been excused if it were an aberration; unfortunately, it is not. After years of skewed financial priorities and allocations, profligacy in unproductive sectors or projects and mismanagement of its borrowings, Maharashtra’s annual budget for 2011-12 shows a fiscal deficit of Rs 22,805 crore; more telling is its debt burden, now at a never-before high of Rs 2,09,648 crore. That’s a 70 per cent increase in debt over five years and a 14 per cent rise over last year (see box). Pawar, who plays with a straight bat unlike his more famous uncle, Union minister and NCP chief Sharad Pawar, says that the debt burden could touch Rs 2,31,926 crore by the end of the current financial.

Maharashtra now has a dubious distinction—it is now India’s second-most indebted state after Uttar Pradesh and, should the projection for 2011-12 hold true, is poised to claim the number one spot next year. It’s indeed a far cry from its reputation for financial prudence and good management earned over the last many decades and cherished till recently. The downslide started with the Shiv Sena-BJP government in 1995-99 when the debt burden shot up four times over the previous year; subsequent Congress-NCP governments have presided over the galloping debt.

The BJP’s Eknath Khadse spells it out, for impact. “That’s nearly two lakh ten thousand crore already and it will become two lakh thirty two thousand crore. I demand a white paper from the Congress-NCP government on how and why the debt is so high”. Khadse, now leader of the opposition in the legislative assembly, was the finance minister in the Sena-BJP regime when the debt began its crazy upward spiral. He has an explanation for what happened in the five years of the saffron parties’ rule. “We had borrowed for major infrastructure projects such as the Krishna valley irrigation projects, expressways, flyovers and so on. Now, that’s not so. In the last few years, all major projects in Maharashtra have been done on the build-operate-transfer basis, which means the state should not end up having such major financial liabilities. Why then such a huge debt?” he asks.

The white paper, if tabled in the legislature, will not be the first one. When the Congress-NCP coalition replaced the Sena-BJP in 1999, its ministers were aghast at the nearly four-fold increase in debt as well as the then fiscal deficit and prepared a white paper on the state of finances between 1995 and 1999. The paper also suggested measures to keep the debt in check, but as a top bureaucrat pointed out, they remained on paper. Successive governments—with former chief minister Vilasrao Deshmukh leading—went on a borrowing spree. Borrowing for what, is the question. Neither Pawar nor chief minister Prithviraj Chavan have convincing answers.

In fact, both of them point to a clause in the federal financial structure that lets them off the hook, but just about. Chavan points out that the debt is around 24 per cent of the gross state domestic product (GSDP) which is still below the 26 per cent cap set by the Union government. Besides, most loans are from the Centre, he justified to the media in a post-budget meeting. In the budget papers, Pawar attempted to list measures to improve the state’s resources but a senior bureaucrat disclosed that it was a feeble attempt, because the administration does not yet have a clear strategy to bring the debt under control or reduce it in the future.

Dr Abhay Pethe, director, department of economics, University of Mumbai, says, “The government’s justification that it is still within the 26 per cent cap does not hold good for a state like Maharashtra. There’s an urgent need to do major restructuring.” Other economists point out that Maharashtra should not have a paucity of funds, given the allocations of the finance commission and other sources. “The debt burden shows that there has been no capital asset creation from the borrowing,” explains Pethe. That’s a bit like borrowing money for a grand party rather than for a business enterprise.

Pawar points to the revenue side; last year’s budget deficit has been replaced by a tiny surplus of Rs 58 crore. This says little about the government and its financial management, though; it was achieved purely on the strength of an unexpected 31 per cent increase in stamp duty and 26 per cent increase in sales tax revenue. Economists point out that such increases are generally considered unaccounted-for bonuses for finance ministers but they should not be offered as justification for a state living hugely beyond its means. Films, especially big-budget ones, often end up going beyond their budgets; a state is just not supposed to do that.

Tags