The former Chennai police commissioner returned to the STF, which he had served earlier, 11 months ago. According to Kumar, in the last six months, the STF had flooded the Veerappan heartland. STF personnel had infiltrated villages disguised as masons, beggars, drivers, mendicants and labourers. Some had worked as civilians for long periods; the encounter on October 18 was a result of an "extraordinary intelligence operation". On a parallel track, the STF were involved in a campaign to "win the hearts and minds of the locals with medical camps, social service".

Intelligence-gathering this time was so meticulous that on the night of the encounter, Veerappan, ostensibly sick, was trapped into using a fake ambulance, an STF-planted vehicle. "The driver was our man, so was the vehicle in which Veerappan and his men travelled," said Vijay Kumar proudly. Obviously, over months of hard, secretive work, the STF had outfoxed Veerappan and forced him into circumstances where he played into their hands.

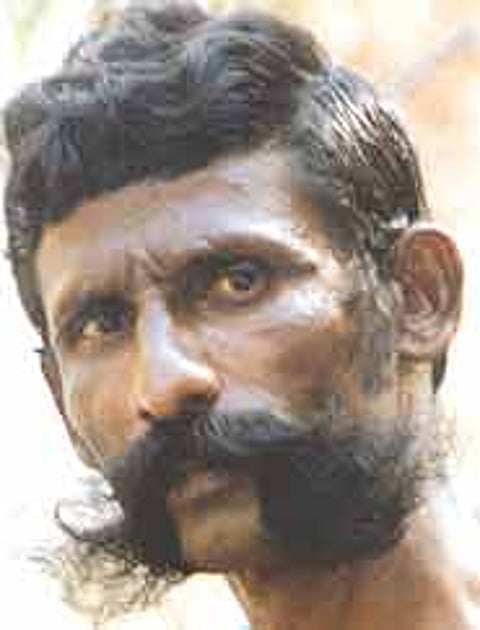

On October 18, when Veerappan stirred out of the forest terrain and was surrounded by STF personnel at Padi, 8 km from Dharmapuri town, he was cornered. Why then was the brigand not captured alive? The police version is they sounded Veerappan out twice on the megaphone asking him to surrender, but he repeatedly fired from within the ambulance. STF personnel were then forced to open fire too, resulting in the death of Veerappan, his No. 2 Sethukuli Govindan, associate Chandre Gowda, and Sethumani, a member of the banned Tamizhar Viduthalai Iyakkam (Tamil Liberation Movement). If Veerappan did open fire, none of the over 40 STF personnel sustained any worthwhile injuries.When asked in Dharmapuri about injuries sustained by his men, Vijay Kumar said, "The injuries are so minor that we cannot even show them to you!"

Run To Ground

The bandit's dead, the forests are calm. Still, questions remain over the 'encounter'. Was it all too convenient?<a > Updates</a>

Says Henri Tiphagne, NHRC advisory committee member, "By Vijay Kumar's own admission, this was a pre-planned extra-judicial encounter." He also points out that in dealing with deaths occurring in encounters, it is mandatory to follow NHRC's revised guidelines laid down in December 2003. The guidelines say: "A magisterial inquiry must be held in all cases of deaths which occur in the course of police action. The next of kin of the deceased must be associated in such an inquiry." So, in Veerappan's case, first an FIR under IPC 302 should have been filed against the STF personnel involved and a CBCID enquiry should have followed. None of this was done; on the contrary the postmortem was quickly concluded in Dharmapuri and the body buried.

The NHRC guidelines also clearly state: "No out-of-turn promotion or instant gallantry rewards shall be bestowed on the concerned officers soon after the occurrence (encounter). It must be ensured at all costs that such rewards are given/recommended only when the gallantry of the concerned officer is established beyond doubt." Both Karnataka and TN showed little regard for these guidelines sent to all chief ministers duly signed by NHRC chairperson Justice A.S. Anand on December 2, 2003.

If Veerappan had survived, charges would have had to be proven in the courts in the 176 cases filed against him in Karnataka and TN. The brigand would certainly then have spilt the beans on the political patronage he received—without which his ivory/sandalwood business would not have flourished. A dead Veerappan was certainly more convenient, given that both states had spelled out the option: dead or alive.

So, what next? The best assessment came from TN STF SP, Senthamaraikannan, a key official involved in tracking the gang: "Absolute peace will prevail in the forest. Tourism will improve." Yes, elephant safaris may become possible. But as long as the political system that sustained the brigand remains unidentified and untouched, we can't be sure that it will not throw up another Veerappan.

Tags