Ever since talk began of Nirupam being inducted into the Congress, Dutt showed his displeasure. What's worse, the buzz in Congress circles was that the former was eyeing Dutt's seat. The unlikely mix of civility and combativeness was suddenly seen in Dutt's demeanour as he prepared to attend a small public meeting called by his party workers to protest Nirupam's entry into the party. The Congress high command termed the meeting "anti-party". It was a gauntlet to the union sports minister. "How can this expression of sentiment be anti-party," he questioned, "Sonia Gandhi was misguided into inducting Nirupam. She was led into believing that I had no objections. This man has called her names, has called Dilip Kumar a traitor." For a man unused to political compromises, particularly on secularism, it was a personal insult. Ironically, Nirupam was present at the Dutt residence to pay his last respects to a man he had so rudely insulted.

He was never the same post-Nirupam's induction. Dutt couldn't quite fathom why the Congress high command had not even so much as consulted him before taking in the former Sena man. All the apologies given by Nirupam failed to placate Dutt. As he saw it, it was a slap on the face of secularism, a plank that the Congress so strongly espouses.

This was not the first time that Dutt felt that Congress had let him down. When his son, actor Sanjay, was arrested in the 1993 bomb blasts case, no one from the party came forward to offer him support or help. In fact, Dutt maintained till the very end that his son was implicated thanks to his own rivalries within the Congress, particularly with Sharad Pawar. When all doors were closed on him, he approached his "personal friend" Bal Thackeray. It was alleged that Thackeray had demanded his pound of flesh, Dutt would not contest the next election from Mumbai Northwest that the Sena wanted to desperately win. As it turned out, Dutt did not contest in 1996 and 1998. It was Sonia Gandhi who persuaded him to return in 1999. He did and wrested the seat back from the Sena. The 2004 victory was his fifth from the constituency.

Slightly agitated after all these years, Dutt said in an interview last year: "I did not compromise in any way. I did what any father would do for his son in trouble. I went to a very good personal friend and requested help. There was no compromise because I wouldn't make any." Now, the secret, if any, remains with Thackeray.

It is to his credit, say Congressmen, that Dutt always rose above his personal tribulations and political rivalries to work for the larger cause. Says senior Congress leader and Rajya Sabha MP Murli Deora, "What Duttsahib brought to the party was unique. He was a politician who always had the feel for social work and did it without waiting for rewards. And he was the personification of the idea of secularism. It bolstered the party a great deal to have him around." In one assembly election after another, the six constituencies that fall in Mumbai Northwest have been largely secure with the Congress. Now Congressmen are not sure if they can be as confident of winning these seats as when Dutt campaigned for the party.

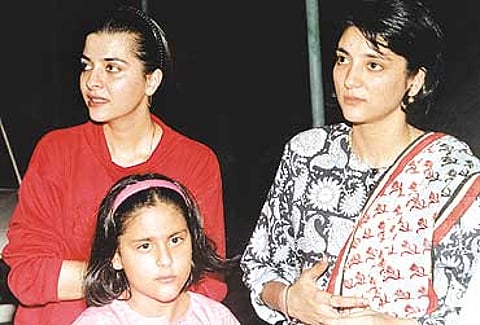

As the plethora of condolence meetings in Dutt's constituency and city ebb, the spotlight is turned on the bye-election for the Mumbai Northwest constituency. It is now a prestige seat. The contenders are many, Nirupam being one of them. Party insiders say that Dutt's persona, work and character has ensured that a certain minimum percentage of votes are not transferable to another candidate—unless it happens to be his younger daughter Priya. Astute Congress leaders have begun talking of fielding her if she is willing but it's too soon after his demise to discuss such matters, they say.

Now, To Fill A Void

Dutt died saddened by the Nirupam affair; the party grapples with the loss

Priya became a primary member of the party last year but she, more than anyone else, is completely hands-on with her father's work and network. She began working with her father almost 20 years ago when as a teenager she accompanied him on his peace-yatras and padyatras. Party sources say that if she contests the election, Nirupam can be legitimately denied a chance this time. Otherwise he remains a strong contender, given his reach and popularity among the Uttar Bharatiyas in the constituency. Nirupam had relied upon this strength to reduce Dutt's victory margin from 87,000 in the last election to about 48,000 in May 2004. "We won't let it happen," says a Congress leader, "If Nirupam contests on a Congress ticket this time, it will be the worst tribute we can pay Duttsahib."

In his death, Sunil Dutt has left behind an unmatched legacy in several walks of life. The Congress, though, will have to learn to face its electoral battles in Mumbai minus him.

Tags