His Record As Minister Of Agriculture...

No Bigger Now Than Baramati?

The IPL disclosures are incidental. Pawar and his party are paying the price of myopia.

- Food inflation at its highest in two decades—16-20%

- Draft of Food Security Act problematic, not yet passed

- He aggressively pursued the introduction of controversial GM food in the country

...And His Family’s Business Interests

- Sugar, grapes, horticulture

- Cooperatives—sugar and other mills and factories; marketing federations; credit institutions

- Partnerships in distilleries

- Stakes in holding companies of some construction and infrastructure majors

***

“Politicians in India,” he mumbled, “never really retire.” No, he hadn’t found the right successor among his hand-picked second-rung leaders to hand the party reins to. “Besides, people still seem to want me,” he said with a smile. He contested from Madha; he won, of course. Now, a year on, Pawar may be excused for wishing he had indeed stepped back when he could do so honourably. Pushing 70, and battling indifferent health, his cup of woe runneth over like never before.

Under fire from all around for his poor handling of the agriculture and civil supplies portfolio, struggling to unsnare himself and his family from the IPL ownership issues, Pawar finds himself in a predicament he would not have imagined 11 years ago when he launched the NCP after breaking away from the Congress—struggling to keep his small political flock together and continue being an asset in the Delhi durbar.

On June 10, the 11th anniversary of the NCP, celebrations were low-key. Pawar spent the day in Mumbai’s Breach Candy hospital, after corrective surgery of the mouth. He also tracked the Rajya Sabha and state legislative council polls.

Dig deeper, and the real picture emerges. The NCP, rather than its president, is atrophying and turning into a sub-regional party, largely limited to western Maharashtra, home to the sugar barons. Pawar bargained hard for key portfolios in the state-level alliance with the Congress both in 1999 and 2004, but this allowed his satraps to entrench themselves in their fiefdoms. Except for R.R. Patil, the state home minister, NCP leaders have promoted their progeny, strengthened their hold over sugar mills and other institutions, acquired stakes in industry and, worse, reopened channels with the Congress on their own.

There’s Vijaysinh Mohite Patil, a former deputy CM who lost the assembly election but threw a tantrum until he was fielded to be elected chairman of the powerful Maharashtra State Cooperative Bank, and his son Ranjitsinh, an mlc, was elected to the Rajya Sabha. There’s Gyaneshwar Naik in Navi Mumbai, with a near-complete hold over rural and urban local self-government bodies. His son Sanjeev is an MP, and his younger son, Sagar, is mayor of the Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation. And then there’s Chhagan Bhujbal, whose fiefdom in Nashik-Yeola—comprising grape farms, factories, educational institutions, and a mansion—is fast turning legendary.

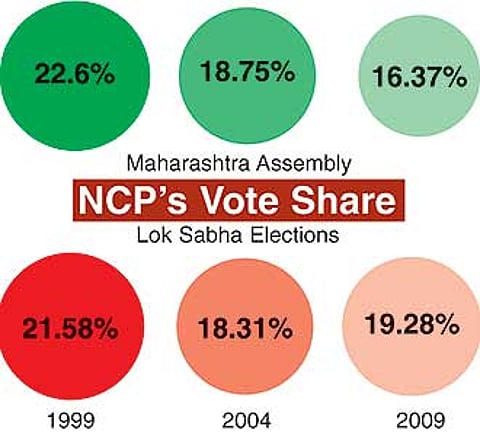

Satraps have grown into challengers. A few directly challenge the “Maratha strongman”, while many indirectly question the authority of his likely successors—daughter Supriya and nephew Ajit. “In 2004, as Pawar shifted base to Delhi, he relied on his second-rung. All of them became big but none delivered Maharashtra to him in 2009,” says B. Venkatesh Kumar, a political scientist with the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS). “The Lok Sabha and assembly polls of 2009 marked the beginning of his decline.”

Pawar, who just about a year ago had aspired to garnering sufficient support to become prime minister, finds himself enfeebled in the corridors of power. Congress spokespersons called him “a key ally” last fortnight; it sounds more like a formality, given the IPL controversy surrounding him, cabinet colleague Praful Patel and their families, and both their ministries under a cloud for non-performance. Congressmen are whispering that the nine-MP party is a liability for the UPA government.

Pawar, seen as “Maharashtra’s voice in Delhi” for decades, seems to be losing that position. “He may still be heard but may not be the last word on Maharashtra he used to be,” says Kumar Ketkar, a well-known editor. “His credibility and integrity, never above reproach, are now at an all-time low. Politicians fail but it’s not supposed to knock their credibility so badly.” Even his friends, or so-called friends, believe that Pawar is his own worst enemy. “Pawar played the politics of money. From money came power and power brought more money. Money helped his politics and now money has done him in,” commented Shiv Sena chief Bal Thackeray, his friend and political rival, in Saamna. Bharat Kumar Raut, a Sena MP, says, “I have seen him for the last 30 years, as a journalist and a politician. He’s a sprinter and not a long-distance runner. He makes short-term bargains and loses out in the long run.”

Pawar’s credibility quotient, never very high with the Congress, has hardly improved with the time the two parties have spent together in power. “The Congress’s mistrust of Pawar goes back many decades, and with good reason too, because he has back-stabbed us many times, but we accept the need to work together,” remarks a well-placed Delhi-based Congressman, also a Maratha. The lament is that Pawar’s singular quality—administrative command and capability—which was showcased to the rest of the country during his stints as chief minister of Maharashtra has failed the UPA, and quite miserably so.

“The wrong that Pawar has done to this country’s agriculture is something no other agriculture minister has ever done before—and he did it deliberately,” says Devinder Sharma, a food policy analyst. “Though the process started in 1991, Pawar has worked to push farmers and farmland into the hands of corporates.” Even discounting for last fiscal’s deficit and erratic rainfall, it didn’t help Pawar’s cause that there was food price inflation and depletion of stocks in government godowns. The UPA’s standing among the people went down. All this worked against Pawar. The lament is that as an agriculturist himself, he should have understood the vicissitudes and pitfalls better.

“It’s a myth that he performs well,” says Venkatesh Kumar. And now even the myth has gone bust. “When P.V. Narasimha Rao sent him back to Maharashtra as chief minister in 1991, the Congress was in a position of strength; by 1995, through sheer mismanagement, he had handed over the state to the Sena-BJP on a platter.” And Raut says, “His failure as agriculture minister is best reflected in the continuing farmer’s suicides, that too in his home state.” The more charitable amongst his critics point out that the farmer-unfriendly policies and corporatisation of agriculture are part of the larger neo-liberal path adopted by earlier governments. “Yet Pawar has played a special role,” says Kumar. “We all remember that Emergency-era statement about crawling when asked to bend. Pawar crawled.”

And then came the undoing of his protege, Lalit Modi. “It’s the least of his crimes; for as the money trail goes, it’s small feed for Pawar, though it has ethical connotations and conflict of interest issues. I believe he got disoriented after his election setbacks last year,” says Ketkar. “He tried to resurrect himself through influencing the politics of sports and trying to bargain politically through control of sports bodies. This has backfired badly. He would rather fight a Jagmohan Dalmiya than Sonia Gandhi.” As revelations trickled out over the last two weeks about the Pawar family’s holdings in two companies that bid for IPL teams—successfully for the Royal Challengers team and unsuccessfully for the Pune team—the spotlight was back on the intersection between Pawar’s politics, business interests, friendships and sport administration functions. “High-level politics works either through friends in politics or friends in business and sometimes a combination of the two,” says Raut. “Pawar relies more on the latter.”

Pawar is not the only one to freely, even if indiscreetly, mix his business and friends with his politics; the heady brew became public at the most inopportune time in his life. “Saheb will come out of all this, he has come out of every crisis,” asserts a close aide of 20 years. But Pawar’s chief regret, never said in as many words, is that the “Baramati pattern”—industrial development, agri-business and education—has been confined to Baramati in all these years.

Tags