"That, ironically enough, was my first brush with Communism," recalls an amused Karat. "My mother, sister and I were evacuated from Burma, along with other Indians. We went to Palakkad, in Kerala, where I spent the next four and a half years, before returning to Rangoon to rejoin my father."

For Karat, the next four years in Rangoon, spent in a railway enclave—his father, Chundoli Padmanabhan Nair, was a clerk in the Burma Railways—are bathed in the golden glow of an idyllic childhood. Home was a wooden bungalow with polished teak floors. The neighbourhood was filled with children. Karat learned to speak Hindi at the Indian school he attended and Burmese from his friends. Those were magical years—watching football matches, for instance, at the nearby 40,000-seat Aung San Stadium with his father (football remains Karat's favourite sport, which he follows to this day). "I remember an Indian team once playing a Burmese team, but I was rooting for the Burmese. I had a certain feeling for Burma already," says Karat. Or playing with friends on the empty platforms of the newly-built Rangoon Central Station. "Very few trains passed through the station, thanks to the continuing insurgency," says Karat, "so we children had the free run of the place, which was walking distance from my home." And then there was the food: while the meals at home were traditional Malayali, there was wonderful Burmese street food in the bazaars waiting to be sampled. And finally, he recalls, the lazy Sunday picnics with other Indian and Burmese families at the lakes that dot Rangoon.

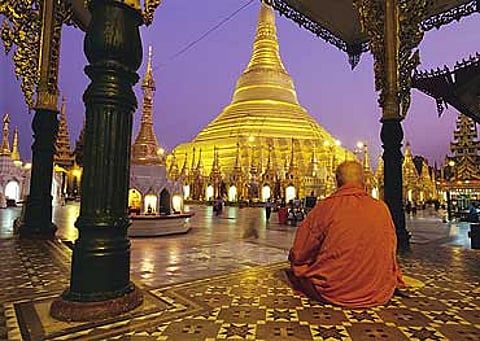

"One of my most abiding memories of that time is the Shwedagon pagoda, one of the most sacred Buddhist temples," says Karat. As he sits in his spartan office at the CPI(M) headquarters, it is evident that more than 50 years later he is still mesmerised by the memory of the radiance that emanated from the pagoda, its great golden stupa dominating the Rangoon skyline. But it was not just the dazzling beauty of the pagoda that drew Karat to it. "People would throng the place not just for worship; it was a meeting place—things happened there." Indeed they did: in 1920, students held a protest strike here against the new University Act which they believed would only benefit the elite and perpetuate colonial rule; and in 1938, oilfield workers established a strike camp here. In January 1946, Gen Aung San addressed a mass meeting at the pagoda, demanding "independence now" from the British. (Forty-two years later, in 1988, his daughter Aung San Suu Kyi too would address an enormous crowd here, demanding democracy from the military regime.)

Of course, Karat didn't witness any of these events—he had only heard about them. But one afternoon, just outside his home, he saw a large body of monks clash with the police, who charged them with their batons. "That afternoon still remains vivid in my memory. I stood there bemused, I had never seen anything like that before." In the years to come, once he joined politics as a student, clashes with the police would, of course, become commonplace.