Examining The Lens

Did television coverage of Anna Hazare’s campaign cross the line? Opinions differ.

This kind of coverage, while it did train its lights on a popular movement, also raised some uncomfortable questions. Was it really a ‘television event’—not in the belittling sense that it existed only on TV, but that its live enactment on the small screen was essential to its unfolding? Did TV package it, or aggrandise it? Did it manufacture consent? In short, would things have gone the way they did without TV? Rajdeep Sardesai, editor-in-chief of CNN-IBN, says, “TV did a fine job in providing a mirror to society by mirroring the support Anna had. But in terms of guiding and questioning the Jan Lokpal bill, we played a lesser role.”

P. Sainath, rural affairs editor of The Hindu, has a different take. “The UPA government busily wrote the manual for the making of a martyr. Anna’s ghost-writers contributed the chapter on the creation of a cult. The broadcast media made a film adaptation of the book,” he says. “Music and bragging rights remain a matter of dispute.” Such discomfiture stems from the aggressive posturing of some TV channels. Ideally, a news medium needs to explain its position so that the viewer can make a well-informed decision. There are many who feel that, this time around, the channels failed to do so. Given the popular sentiment, it seemed difficult for some TV anchors and reporters not to be carried away.

| “Self-regulation doesn’t really work. See what it has achieved in the markets. The govt should take the initiative.” Sitaram Yechury, CPI(M) leader |

| “A movement can’t be created by the media. If media supports an illegitimate cause, people will see through it.” Arvind Kejriwal, Member of Anna’s team | ||

| “TV did a fine job in mirroring what society felt. But we played a lesser role in terms of questioning the Jan Lokpal bill.” Rajdeep Sardesai, Editor-in-Chief, CNN-IBN |

| “In covering Anna, much was neglected. You need balance in coverage. Josh ho, lekin hosh ke saath ho.” Sharad Yadav, JD(U) chief, NDA convenor |

True, in this digital age, TV news channels have a crucial role to play in shaping public opinion. And this can influence government decisions. Which is why the political class leans so heavily on TV coverage, more so at the time of elections. If we rewind to what followed after the hijacking of IC-814 in December 1999, we have a classic example of television’s reach. The images of troubled relatives sobbing profusely forced the government to change its hardline stance and agree to some of the demands made by the hijackers. The horror of the 26/11 terrors attacks on Mumbai was captured in such detail that it made the Centre and the Maharashtra government take long-term action. This is not to say that TV alone achieved that. But it helped bring a new kind of focus on the situation. But it was an observer.

As far as the Anna stir goes, TV’s role was much more. It almost campaigned for the anti-corruption cause. Had it not been for the TV channels, many scenes from the movement would have escaped public attention, among them the impromptu jig of ex-cop Kiran Bedi, who was part of Anna’s core team, her barbed attack on politicians and the strange outburst of actor Om Puri. Perhaps such actions may have been prompted in the first place by the fact that there was so much coverage. The midnight appearance on TV of Union finance minister Pranab Mukherjee, issuing a disclaimer that he was misquoted, demonstrated the power of television.

Never has any debate on air been so shrill and polarised. It killed nuanced debate: it was as if you were either against corruption or for it. Not merely differing on the means to curb corruption within the democratic framework.

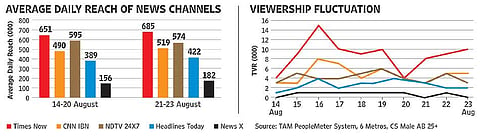

It is also no surprise that the leader of the “let’s back Anna” pack among English TV channels, Times Now, was referred to as the ‘Bangaali Dabba’ by Sharad Yadav, who also urged fellow MPs to at least help put an end to the unceasing commentary unleashed by the channel if they couldn’t help end the protests. Officially, Times Now refused to comment, but sources in the channel say the movement was bigger than the debate on whether discussions were calculated to induce TRPS. “It was difficult for us to ignore what was happening on the ground,” says a source.

| Jessica Lal murder, April 2009 onwards The model’s killing led TV channels and the media to launch a campaign to bring her killer to book. | IC-814 hijacking, Dec 1999 Footage of wailing relatives of the hostages brought pressure on the government to give in to the hijackers. | |

| Gujarat riots, Feb-March 2002 India’s first televised riots brought violent scenes into our living rooms. Exposed the state’s complicity. | 26/11 attacks on Mumbai Continuous coverage of the attacks, visuals of the NSG in action compromised the government’s ability to react to the terror attack. | |

| T. Chandrasekhara Rao’s Telangana fast, Nov 2009 Telugu TV channels played a major role in boosting the campaign by giving it round-the-clock coverage. | Hazare’s campaign, Aug 2011 Seamless reporting of the anti-corruption campaign, chiefly at Ramlila Maidan, acted as a force multiplier. | |

However, Sharad Yadav who led the charge against the media in Parliament says, “The country is not run by discussions on TV channels but by debates in Parliament.” Later, perhaps aware that his statements in the House had raised concerns about a possible government control on media, Yadav was more charitable when he said “the ideal should be that we both (politicians and the media) improve ourselves.” While Sharad Yadav is entitled to his position, RJD leader Laloo Prasad Yadav was clear that politicians and those in Parliament were the real newsmakers, suggesting perhaps that media played a subservient role on the political landscape. Again, a comment less true now than before.

It is perhaps the near-absence of dissent on the channels that makes the CPI(M)’s Sitaram Yechury say, “This is a serious issue. Self-regulation doesn’t really work. With the meltdown, we have seen what self-regulation achieved in the markets. The government needs to take the initiative to bring together editors and broadcasters so that a solution may be evolved with a consensus.”

But one thing is clear. It would be horribly wrong to say the Anna movement was totally the creation of television and perhaps far-fetched to suggest conspiracy theories about the 24x7 coverage. “At points, it occupied the missing organisational space of that movement and often mobilised for it. In that sense, some of what happened could be said to be media-driven,” says a media analyst. Adds Arvind Kejriwal, a key member of Anna’s team, “The media cannot create the movement. At best, it can only multiply and take it further. If media supports an illegitimate cause, people will see through it and won’t support it.”

By Anuradha Raman with inputs from Debarshi Dasgupta

Tags