Why The Caged Parrot Is Singing

A New-Found Agency?

Is the CBI really targeting UPA ministers without fear or favour, or is there a twist to its recent fervour?

There is a lot of buzz on why the CBI has been ‘caught’ biting

- New director Ranjit Sinha is an honourable and upright man who thinks, after the CAG, it is CBI’s turn

- As per new rules, the CBI chief has a fixed tenure; he has nothing to lose by rocking the boat

- With UPA government’s days numbered, there is no harm in aggressive posturing ahead of polls

- Different groups in Congress are targeting or backing Ashwani Kumar and Pawan Bansal

- Going after Bansal following Ashwani Kumar episode could be CBI insurance against blowback

- Any of the 12 companies being investigated by CBI may be trying to scupper the probe

- CBI chief, with his perceived lack of political clout, caught in organisation’s internal dynamics

***

Director’s Cut

The last four CBI directors have been given lucrative post-retirement assignments carrying attractive perks and privileges

- Amar Pratap Singh (2010-2012): Member, Union Public Service Commission

- Ashwani Kumar (2008-2010): Governor, Nagaland

- Vijay Shankar (2005-2008): Member, Commission on Centre-State Relations

- P.C. Sharma (2001-2003): Member, NHRC. Granted a second five-year term by UPA.

***

On his first day in office after taking over as the director of the Central Bureau of Investigation in November last year, Ranjit Sinha told his team that he was not a ‘jehadi’. He did not believe in sniffing out stink because there was enough of it in the air anyway, but he would not turn his nose away if it was in his face. Five months down the line, he has raised enough stink himself for his line to Raisina Hill to stop ringing. A shell-shocked government, suddenly uncertain about how to deal with what used to be a well-behaved domesticated pet, has plenty of egg on its face, and at least two Union ministers running for cover.

“It is neither an unruly horse nor a caged bird; it is more like the washerman’s ass, which nevertheless lands a kick or two at times,” quipped a CBI insider this week. This was after the Supreme Court, hearing the alleged Rs 1.86 crore coal scam which implicates the bold and the beautiful of India’s political and corporate world, called the nation’s premier investigating body “a caged parrot speaking his master’s voice”, and gave the master, the government, a little less than two months to make changes in the law to allow the hapless animal to move around freely, or in other words, make it more autonomous and insulated from influence.

In duly placing on record India’s worst-kept secret that, for all its claims of autonomy, the ‘Congress Bureau of Investigation’ was little more than a poodle of those in power, Sinha, 59, has emerged as an accidental hero: a victim in the eyes of some, not quite in the eyes of many. After it exposed Union law minister Ashwani Kumar’s editorial skills and railway minister Pawan Kumar Bansal’s headhunting abilities, all in the course of a week, there is plenty of buzz in Delhi on who, if anyone, could be behind this all—and whether some dark conspiracy lurks underneath?

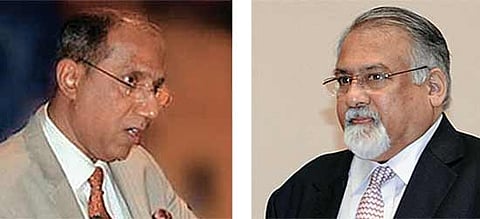

Pawan K. Bansal, Rail minister; Ashwani Kumar, Law minister

The first signs of intrigue came when news broke in mid-April that Sinha had met Ashwani in the latter’s office to “share” the CBI’s status reports in the coal scam. In the good old days, when the watchdog snapped and retreated on command, a denial would have sufficed. But the apex court, hearing a public interest litigation seeking the cancellation of all coal blocks allotted to private companies, pointedly asked whether the agency’s findings had been shared with the political executive. Inexplicably—or perhaps not—attorney-general Goolam Vahanvati and additional solicitor general Harin Raval replied in the negative, prompting the court to ask the agency itself to file an affidavit to that effect.

Sinha, say insiders, faced intense pressure to say the same in the affidavit. Earlier, there was much hullabaloo on television when he was caught on camera visiting V. Narayanasamy, minister of state in the PMO, a day before he was to file an affidavit in court. His advisors, however, told him there was no way he could bluff his way out and it was better to come clean. That affidavit put the law minister in a spot because Sinha detailed the changes Ashwani had made—deleting two paragraphs from one of the 12 status reports that the agency was to file, prompting Supreme Court justice R.M. Lodha to say that the very “heart of the report had been altered”. Sinha had tried to rationalise it by asserting that the CBI was part of the government (it operates under the Department of Personnel and Training and a law ministry official sits in the CBI office 24x7), and that he had shared the report with the law minister, not an outsider. But the damage had already been inflicted. It was against the clamour for the minister’s sacking/resignation and the sine die adjournment of Parliament that the SC was going to adjudicate matters.

The drama quotient went up by a few notches at this juncture when the CBI, out of the blue, arrested the nephew of the railway minister in Chandigarh on May 4. The surveillance wing of the agency, tucked away in a hutment behind an inconspicuous CBI safehouse on Akbar Road in New Delhi, they say, was activated following a tip-off. And it took them six weeks and more than 100 hours of recorded conversation before they ‘stumbled’ upon the intelligence that a sum of Rs 2 crore was to be delivered somewhere in Delhi for a posting in the Railway Board. Were the government bosses in the loop? If so, which one?

“At that stage, the operation could be stopped only by the director,” claims a CBI official. “But he gave us the clearance to go ahead.” Why wouldn’t he, says a retired DGP? Had he halted the operation, it would certainly have leaked out and created fresh trouble for him. “Why would he take that risk?” He had no other option. Armed with a what it calls a “watertight case”, the agency is gearing up to grill the railway minister. The grapevine says another Railway Board member is also under the scanner and may well be arrested.

Even the sceptics are bewildered at the agency’s gumption to take on the railway minister and the speed with which they have moved on the case as compared to say, Bofors. In March, the CBI director had given clearance to a raid on DMK leader M.K. Stalin’s house in Chennai. It was acting on a complaint lodged in the Tamil Nadu capital, and was investigating the violation of customs rules in the sale of imported luxury cars, causing a loss of Rs 48 crore to the exchequer. It did manage to impound 28 such cars, even if none from Stalin’s house, which failure it blamed on media hype that presumably alerted the culprits and left it with all the explaining to do.

Picture of doubt Sinha leaving V. Narayanasamy’s residence. (Photograph by Indian Express Archive/Anil Sharma)

Tired of being at the receiving end of both the government and the Supreme Court, the CBI seemed to be flexing its muscle and sending out a stark signal to the political class. Most observers appear baffled by the agency’s sudden hyperactivity and unheard-of moves, so patently against the interests of the government, and so unimaginable till recently? How could a historically servile investigating agency find the steel to rock the government in a matter of months? Has the pet gone stray?

It is a measure of the confusing times we live in that no one’s quite sure whether the agency has suddenly discovered teeth or whether it is merely going through the motions to enable the government to claim that no other regime had allowed the agency so much independence. There is also no telling whether it’s the government which is riding the tiger or the CBI director. Or whether the Supreme Court’s injunction will now ‘liberate’ the agency from its political masters and they would finally agree to end the agency’s departmental slavery.

It’s much ado about nothing, the sceptics argue, and the agency remains as servile as ever. “In the Stalin case,” they argue, “nothing was recovered and the DMK leader was spared.” If anything, the prime minister and finance minister distanced themselves, voiced their dismay and publicly rebuked the agency for its “unfortunate timing”. This, when the natural assumption was that the UPA itself had ordered the raid, barely two days after the DMK had withdrawn support to its government at the Centre.

As for “the decision to appeal against the acquittal of former Congress MP Sajjan Kumar,” the critics go on to say, “it actually gives the government a breather and time to contain protests. And the CBI director’s affidavit before the Supreme Court has left the law minister largely unscathed.”

There is also speculation about Sinha’s own background. It dates back to 1996 when Sinha was posted as the CBI dig in Patna, and U.N. Biswas, then a CBI joint director, had requisitioned the army for arresting the then Bihar chief minister Laloo Prasad Yadav in the fodder scam. Both the CBI and the courts had reprimanded Biswas, who had in turn accused Sinha of being the CM’s informer. In yet another instance when CBI director Joginder Singh had directed Biswas to submit a status report Sinha had prepared, Biswas, now a minister in the West Bengal government, had dramatically announced that the status report with the court had neither been seen nor vetted by him. Sinha had apparently bypassed the JD, his superior, and sent the report straight to headquarters. Given this history of Sinha’s, BJP leaders Arun Jaitley and Sushma Swaraj had opposed his appointment as CBI director and even written to the PM in protest.

Likewise, the member of the Railway Board who has now been arrested in relation to the railway recruitment case says Sinha is settling an old score by implicating him. Mahesh Kumar claims to have been close to the then railway minister Mamata Banerjee and insinuated that Sinha, who was heading the Railway Protection Force (RTF) then, had to move on because of a tiff with him. A livid Sinha, when told of this insinuation, let loose a volley of invectives before asserting that he had never set his eyes on Kumar, let alone have a tiff with him.

He has enough friends and colleagues, however, to put a stamp on his character certificate. “He is unassuming to the point of being laidback and is unlikely to be adventurous or invite trouble,” says a friend. He is not cast in the mould of a Vinod Rai and has less drive than the CAG. He is known more as an easy-going, affable policeman. Sinha’s two children are employed with the Intelligence Bureau and the State Trading Corporation in relatively obscure jobs. “He does have powerful friends, some of them businessmen and coal transporters and others with direct links to powerful politicians; he could have helped his children find fancier jobs outside the government and PSUs. But he didn’t,” a long-time friend of his tells Outlook. People who have known him since his days as a probationer agree that he is no David taking on Goliath. “He is far too gentle and polite and far too eager to please everyone,” says another friend.

Caught out! ASG Harin Raval and attorney general G. Vahanvati

And so, the riddle remains. If the CBI is not free and if Sinha is not raring for a showdown with the government, what explains this sudden burst of activity against the government?

This brings us to the larger swirl of controversy that is doing the rounds. Many are wondering why the agency has gone after Ashwani Kumar and Pawan Kumar Bansal, both political lightweights, when there are hundreds of other, more corrupt politicians in New Delhi. Both the targeted ministers are from Punjab, the prime minister’s home state, and both his political appointees (refer ‘Kaur group’ vs ‘core group’ SMS). Their rise in the government and growing influence has not gone down too well within the party and they are clearly dispensable.

The simple theory is that CBI officials, upset at the abrasive law minister ticking the agency for its poor command of English, themselves leaked details of their meeting with him. Once Sinha dug in his heels on the issue despite the pressure, the agency decided it had nothing to lose by going on the offensive and arresting Bansal’s nephew as well. It could be used as ‘insurance’ or a bargaining chip, specially if the government tried to get rid of both the law minister and the CBI director. Sinha, at the very least, would then leave in a blaze of glory.

In any event, the current battle is unlikely to last long. The agency, say CBI officers, is not a constitutional body like the Election Commission or the office of the Comptroller and Auditor General. It is actually a department of the government and the CBI director does not even enjoy the powers of a secretary to the government. “The director cannot even purchase a mobile phone on his own,” says a CBI officer. So much for autonomy.

It is for this very reason that the agency has been clamouring for a degree of functional and financial freedom. One reason why its track record is so pathetic in investigating defence deals and major cases of corruption, say insiders, is the necessity to investigate abroad and get approvals for the same. “Very often, the government would approve a visit abroad for two or three days,” they complain, pointing out that it took a lot longer to investigate in foreign countries.

The UPA, ironically, has invested a lot in the CBI. Its budget has gone up substantially, though agency officials say it has always been around 30 per cent lower than what it asks for. The government has also sanctioned 71 special CBI courts, which has led to the speedy disposal of cases, which between 2010 and 2012 has gone up by 60 per cent. The number of vacancies too has come down in the past few years, from over 1,700 to a little over 800. And the government has not outrightly rejected the proposal to sanction 2,000 additional posts.

In a country with runaway corruption and where the annual Union budget in 2013 is five times higher than in 2004, the CBI registers only around a thousand-odd cases every year and investigates a thousand more. Anti-corruption cases constitute only one-third of this number while Disproportionate Assets (DA) cases are less than 10 per cent.

Giving the CBI more teeth and making it more independent will, therefore, require a lot more than a few changes in the law that the Supreme Court has recommended.

***

Not Quite According To Script

M.K. Stalin

March 21: Two days after the DMK pulled out of the UPA, CBI noisily raids DMK supremo M.Karunanidhi’s son, M.K. Stalin’s house in Chennai. The ostensible reason: the violation of customs in the import and sale of luxury cars. Finance minister P. Chidambaram, among others, slams the raid. CBI says the case was approved a month earlier, on February 12, and had been registered the day before the raid.

Impact: Manmohan Singh government had just lost 14 MPs in Parliament. The estrangement is complete.

***

Ashwani Kumar

April: First, the Indian Express reports that CBI will tell the Supreme Court that law minister Ashwani Kumar looked at coal scam report. Then Sinha is caught on cameras captures the CBI director leaving MoS V. Narayanasamy’s residence. In response to a PIL demanding a special investigation, CBI chief confirms in separate affidavits the meetings and the changes made to CBI’s report.

Impact: Demand for the resignation not just of the law minister but also of the PM who held the coal portfolio for some time

***

Pawan Bansal

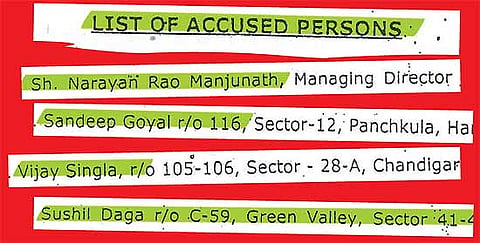

May 4: Even as UPA government reels under CBI disclosure, railway minister Pawan Bansal’s nephew is arrested for accepting Rs 90 lakh as first instalment towards a bribe to secure a posting for railway board member Mahesh Kumar. CBI says it had put the nephew’s phones under surveillance in end-March. Nine people are held. Bansal claims innocence, but CBI likely to interrogate him.

Impact: Another blow to Manmohan Singh government, dark whispers of PM’s appointees from Punjab being under attack

***

Sajjan Kumar

May 7: A Delhi sessions court acquits Sajjan Kumar in end-April of the charge of leading mobs in killing Sikhs following the assassination of Indira Gandhi in 1984. The court says the evidence against Sajjan Kumar is unreliable and not credible. Six others are found guilty. CBI quickly bounces into the picture and says it is going to appeal against the acquittal verdict.

Impact: The Congress can no longer keep accusing the BJP of the 2002 Gujarat riots

By Uttam Sengupta with Chandrani Banerjee

Tags