A Missing Chakra

32 Spokes Of Wisdom

Our national symbol, the Ashoka pillar, has an upper chakra missing. An MP pointed it out to Nehru, but was ignored.

- India’s national emblem, with the four lions and the Ashoka Chakra at the bottom is erroneous, say some

- The original Ashoka Pillar at Sarnath has the Chakra on top, symbolising spirituality over strength (the lions)

- The chakra on our flag was meant to be ‘Mahadharma chakra’, with 32 spokes, not 24 as we have now

***

In the Mookherjee household on Calcutta’s plush Ekdalia Road, it has been a hush-hush after-dinner topic for four generations now. “My grandfather often narrated how shocked he was that Nehru allowed a distorted symbol to pass off as the national emblem of our country,” Pradipta Mukhopadhyay tells Outlook. Mukhopadhyay, the grandson of Radha Kumud Mookherjee, historian, scholar and Rajya Sabha Member of Parliament during Jawaharlal Nehru’s premiership, is in possession of documents and letters exchanged between his grandfather and India’s first prime minister which reveal that the Ashoka stambha or pillar, adopted as India’s national emblem, is not a replica of the original but of a truncated one. More significantly, not only did Nehru know about it, but when alerted by Mookherjee, who initiated a signature campaign to rectify what he termed a grave ‘historical error’, he brushed it under the carpet.

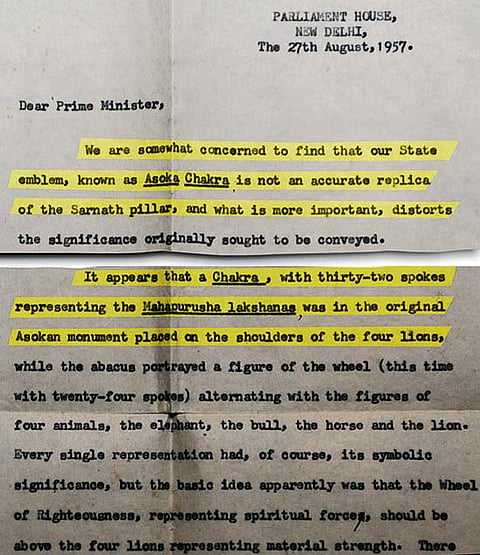

In his letter to Nehru dated August 27, 1957, Radha Kumud wrote, “We are concerned to find that our state emblem, known as Ashoka Chakra, is not an accurate replica of the Sarnath pillar, and what is more important, distorts the significance originally sought to be conveyed.” (See full text of letter). In the letter, which was signed by nine other MPs, including influential leaders of the time such as Hiren Mukherjee, Kishenchand and Sucheta Kripalani, he points out what the error was: “It appears that a ‘chakra’ with thirty-two spokes was, in the original, placed atop the shoulders of the four lions. The basic idea was that the wheel of righteousness, representing spiritual forces, should be above the four lions, representing material strength. (However) there is evidence to show that this top wheel fell off the shaft on which it rested and so in the Sarnath Museum one sees the lion capital without the top.”

Shyamal Ghosh, editor of the Bengali historical research fortnightly Deshkaal, who has written extensively on the subject, decodes the complex issue and puts the matter in perspective. That the Ashoka Chakra would be adopted as the national emblem was decided during the Constituent Assembly debate of 1949, he says. Nehru presided over the debate. Though there were a few voices of dissent when the ‘chakra’ or wheel was suggested as a motif, not just for the national emblem, but also for the national flag, by those who felt that it had too much religious connotation, Nehru argued that it was an integral symbol of India’s freedom movement and hence should adorn both the national flag and emblem. This was also the majority view in the house. The ‘chakra’ also found resonance in the ancient Buddhist principles of the land, epitomised by the era of Ashoka, a period of peace and strength. “The Ashoka stambha or pillar found in the ruins of Sarnath in Uttar Pradesh, which were adorned with a number of chakras, therefore, was the most appropriate choice,” says Ghosh.

At the circular base of the original Ashoka pillar is an abacus girded with a frieze which is embossed with sculptures of an elephant, a bull, a horse, and a lion, each separated by intervening chakras and one 24-spoke wheel, symbolising the Buddhist chakra representing the 24 ‘achari dharmas’ or ways of life. However, according to Ghosh, the chakra that was supposed to make its way into the Indian flag and atop the shoulders of the four lions of the Indian emblem—as per the decision of the Constituent Assembly debate of 1949—was the Mahadharma Chakra, which has 32 spokes. “This Chakra is based on the Buddhist principles of ‘4 Truths’ and ‘8 Ways’ of Life: (4 x 8 = 32). The original Ashoka stambha or pillar had one such chakra atop the shoulders of the four lions, of which Radha Kumud Mookherjee and his fellow MPs wrote to Nehru. When the designers were sent to Sarnath to make the replica for the national emblem, this Mahadharma Chakra must have either been missing or just fallen off, as Radha Kumud pointed out,” says Ghosh.

Pradipta, who was 12 when his grandfather died at the age of 83 in 1963, remembers him as being a principled man with a strong sense of right and wrong. “He didn’t tolerate shoddiness, especially when it came to matters of great importance as our national symbol. He often spoke about the need to uphold the image of India as a country of tolerance and spirituality as much as a nation of strength and fearlessness. So he could not accept this.”

In his letter, Radha Kumud writes, “We feel our state emblem should not embody in itself, as it were, a historical mistake. The sheer accident of the wheel being detached from the pillar should not justify a truncated copy of the original sculpture. Besides, the chakra, which is now only engraved in the abacus, does not convey the significance and symbolism of the original, which stresses the superiority of spiritual values. It will be in conformity with our principles and ideals if we correct the mistake. If we have wanted to revive the Ashokan ideals, as indeed we have done, let us not perpetuate a mutilated variant of this monument.” Recognising the logistical difficulties of the rectification he was suggesting, he even addressed the issue in the letter thus: “The cost of the change is estimated not to exceed a couple of lakhs.”

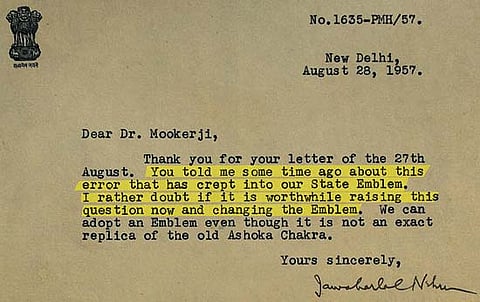

“What stunned my grandfather was Nehru’s response,” says Pradipta, who remembers his own father, Radha Kumud’s son Pradyumna, once telling him that “he just couldn’t believe it.” In a terse four-sentence reply, written the very next day—reflecting, no doubt, the fact that he was unwilling to put much thought into the matter—Nehru said there was no need for a change. His August 28, 1957 letter addressed to Mookherjee read: “I rather doubt if it is worthwhile raising this question now and changing the emblem.” Interestingly, Nehru’s letter does mention an earlier instance, when Radha Kumud had pointed out the error to him. “You told me some time ago about this error that has crept into our state emblem,” he recalled to Mookherjee.

“My grandfather had told my father, ‘You should have seen the look on Nehru’s face when I first pointed it out to him in Parliament. He was dumbfounded. I have never seen Nehru at a loss for words as he was on that day,’” Pradipta says. Incidentally, it is Radha Kumud’s great grandson, Pragyan Kumud, who has decided to “do something about this once and for all”. The 21-year-old student of Calcutta’s Jadavpur University says, “I don’t know why my great grandfather or even my grandfather or father didn’t pursue the matter.” He is now in the process of collecting all the documents and letters from hidden corners of the bookshelves in the house and making a case for it. “I will go up to the highest authorities until the change is made,” he vows. “There is something in symbolism, otherwise we would not need national emblems. Maybe, if the chakra of peace was put back into its rightful place, our country would witness a change for the better.” Some would argue that this is an youthful, over-optimistic proposition, considering that the country has come to identify with the Ashoka pillar as its national symbol for so long. But Pragyan Kumud, like his great grandfather, believes that the majority of Indians would like to see the symbol of spirituality and tolerance (the chakra) lord over the symbol of brute force (the lions), though both are integral to a modern nation-state. It’s a point to debate.

Tags