Optimism has returned to Paan Gali, as have shoppers. Customers demand every item advertised on Indian TV channels. Illyas Beg, a shopkeeper, thinks he will now have a steady supply of Indian goods to match the demand. "After the Dosti bus service, the revival of rail and air links will give a boost to our business, which depends on friendly relations between the two countries." This demand isn’t just about the quality of Indian goods or monetary benefits, argues schoolteacher and shopper Dr Abdul Rahman, savouring the Indian paan he’s chewing. "It’s a reflection of psychological attachments, about the similarity in tastes. It shows how bright the prospects are of negating the misconception of alienation between Indians and Pakistanis, if they are given the opportunity," he says.

That Iron In The Soul

A thaw in the Pakistani mindset is discernible. But if you thought they will trade Kashmir for peace, perish it <a >Updates</a>

The opportunity has come after the governments of India and Pakistan realised the futility of habitually flexing their muscles and indulging in crass jingoism. The Wagah border has been opened for people; air and rail links should be re-established soon. But if you were to feel that these measures can efface the memory of bloody history, think again. It is indeed much easier to seal a hole in a baby’s heart, a la Noor Fatima, than to "liberate the future from the past".

As the Outlook team wended its way through the bustling Paan Gali to Anarkali Bazaar, where Indian sarees can be purchased, and began to probe beyond their consumerist instinct, Kashmir started to surface with familiar frequency. Says Shakoor, a cloth vendor in Anarkali, "Our similarities can help bring the two countries closer and then make way for a solution to the Kashmir problem." Shakoor’s remarks are typical of most here: they aren’t willing to forget Kashmir, barter it for robust Indo-Pak relations that could boost their business. This cannot be dismissed as just a view of the hoi polloi. Even defence analyst and author Dr Hassan Askari Rizvi agrees: "Friendship with India can be very fruitful. But a peaceful resolution of Kashmir is a pre-requisite for this."

Such a blend of views that seem mutually irreconcilable—warmth for India and a stubborn insistence on Kashmir—are not confined to Lahore. At a kiosk in Rawalpindi Sadar, our posers on Indo-Pak relations spark off a veritable debate. Bilal Ahmad has the last word: "Of course, Kashmir is important, and India will have to give the Kashmiris their rights. But why should we be fighting with the Indians?" His view is unanimously endorsed. An onlooker nods his head and adds, "It’s true, hum ko larai-sharai nahin chahiye (we don’t want any conflict)."

In Rawalpindi Cantonment, army officers don’t talk on record. Outlook spoke to quite a few, and nearly all of them ruled out the option of war, unless waged in defence. But the K-word pops up regularly in the conversations; it defines their worldview. One of them points out, "The sacrifices of Kashmiris and Pakistanis should not go in vain. But the Kashmir problem should be resolved through negotiations, not war."

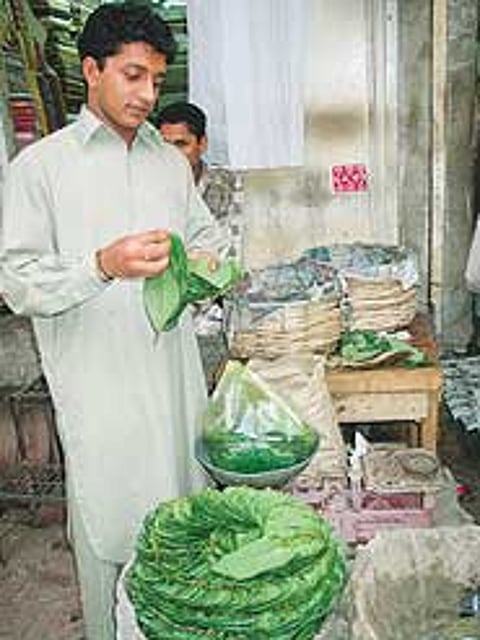

Sarees sell briskly at shops in Paan Gali, a crowded market in Lahore. Shoppers hope Indian goods will be easily available if relations improve.

This complex of attitudes finds its echo in the Gallup-Outlook opinion poll, the first-ever conducted by the Indian media in Pakistan. People often emphasise those aspects of statistics that are in accordance with their ideological inclinations. Pakistani peaceniks are no different. For them, it would be immensely heartening to see the opinion poll show 42 per cent of Pakistanis supporting the resolution of the Kashmir problem through negotiations with India; war as an option comes a poor third. They would find equally remarkable that only six per cent of Pakistanis rate chances of war with India as high (see chart). Comparing the Outlook poll with the ones Gallup did in earlier years, Dr Ijaz Shafi Gillani, chairman, Gallup Pakistan, says, "When leaders of the two countries meet, the percentage of people supporting bilateral negotiations begins to gallop."

Yet, for Indian readers, these findings could throw cold water on their expectations. Support for negotiations, they could argue, essentially reflects the acceptance of reality by the Pakistanis: their army can’t possibly win Kashmir through war. They could point to other two aspects of the poll findings—79 per cent want Kashmir to be resolved first; 69 per cent don’t accept the Line of Control as the international border—and ask: really, what has changed in Pakistan? These views remain as hardline as they ever were.

But this rationalisation is possible, and valid. For a moment, imagine you are a Pakistani brought up on the staple of ‘Crush India’ rhetoric; who has been taught for over five decades to consider Kashmir as the territory India has occupied; who has suffered the ignominy of India truncating Pakistan—and you will, perhaps, find it astonishing that 42 per cent of Pakistanis are willing to wave the white flag and sit at the table.

Outlook talked to an array of politicians and analysts who were not privy to the findings of the Gallup-Outlook poll. Most didn’t need the certitude of statistical findings to discern a change in the Pakistani attitude towards India. For instance, columnist Ayaz Amir feels the ‘Crush India’ rhetoric has little lure for Pakistanis. "Circumstances, necessity and reality have together brought about the transformation," he says. "First, the militant uprising by Kashmiris proved that this was not going to bear any fruit. Finally, 9/11 and pressure from the Americans and Indians forced the establishment to soften its stand. If there was a U-turn on the Taliban, then pressure also saw us soften our stand on Kashmir." This easing of attitude has also impacted on the people, making them understand the futility of hoping for a militaristic option.

Imtiaz Alam is a delighted man today. As convenor of the South Asian Free Media Association, it was at his organisation’s invitation that the Indian parliamentary delegation visited Pakistan last week. And the response they received was indeed unprecedented, yet another indicator of the changing mood in Pakistan. Alam credits that little patient from Pakistan, Noor Fatima, for playing a significant role in the transformation. He explains, "Even those in Pakistan who have anti-India sentiments and a rigid stance on Kashmir, and who are indifferent to the peace initiative, view the care and affection showered on Noor as simply extraordinary."

Indian soldiers in the Batalik region during the kargil war

Make no mistake: anti-India voices will not disappear overnight. They might even become shrill in the competition between peaceniks and hardliners for a larger share of the Pakistani mind. For instance, Lashkar-e-Toiba founder Prof Hafiz Mohammad Saeed insists, "Dialogue will never resolve the Kashmir dispute. The Pakistan army should get ready to wage a war against India to liberate the oppressed people of Kashmir." Such voices in Pakistan will continue to command a substantial constituency until the two countries begin to address the contentious Kashmir issue in right earnest. Says senior political analyst M.B. Naqvi, "An improvement in Indo-Pak relations will make many here ask, what will happen to Kashmir? Should we forget about it? Not necessarily. Pakistan should think of peaceful ways of resolving the Kashmir issue. Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam leader Maulana Fazlur Rehman showed the way on his recent visit to India."

Considered a vocal proponent of jehad, and popularly perceived to have nurtured the Taliban, the maulana provided a new impulse to Indo-Pak relations through his endorsement of resolving Kashmir through negotiations. Jehad can’t be continued indefinitely, he argued. Such pronouncements have had a ripple effect on the people at large here. But this impulse could lose its efficacy and momentum should India delay its response on Kashmir. Says Dr Shirin Mazari of the Institute of Strategic Studies, Islamabad, "If the Indians keep insisting on converting the Line of Control into the international border, then Kashmir can’t be compromised." In other words, the hardliners will wrest the initiative.

Many analysts feel it is difficult to address the contentious Kashmir issue in the prevailing ambience of distrust and suspicion. They say it is of vital importance to improve people-to-people relations and "rationalise," as I.A. Rehman, director of Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), puts it, "the alienation among the citizens." It’s only then the two countries can talk on Kashmir. Dr Mubashar Hassan, convenor of Indo-Pak Solidarity Front, explains why: "Given the fact that no government can afford to take decisions that would not go down well with its public, a settlement of the Kashmir dispute can only come about when the civil society in both India and Pakistan, as well as in Kashmir, has been convinced of the urgent need for a settlement that can satisfy all three parties to the conflict."

Hassan says lessons must be learnt from the past: Indo-Pak talks on previous occasions have ended up with both sides reiterating their respective positions on Kashmir. "Future talks too are doomed to fail," says Hassan, "unless there is a sustained pressure from the civil society on political leaders to tone down on fiery nationalistic rhetoric, address the aspirations of Kashmiris and prepare to make compromises for the sake of peace and progress in the region as a whole."

Some say they can sense the wind of change blowing through the Pakistan foreign office. Says former general Talat Masood, "It appears that they are now saying, ‘Let’s take a political route and set aside the Kashmir issue for the moment.’ Its resolution will eventually come, though no one has a solution yet. Gen Pervez Musharraf has taken a chance. New Delhi, too, has to reciprocate. Till now it has said it is not willing to talk."

One person who should know about the changing mood in the foreign office is Jalil Abbas Jillani, who was appointed director-general of the South Asia Desk after New Delhi expelled him. Jillani says the desire for peace has always been there. "You saw the euphoria in Lahore and later in Agra," he points out. "This kind of frenzy is always there. But people also want a permanent end to this conflict. How do you go about resolving Kashmir? We should have a sustained dialogue which should not be broken."

Pakistanis want peace, and yet they are not prepared to accept the LoC as the international border. Does that sound confusing? Well, it all depends on how one views it: a glass half-empty or half-full.

Amir Mir in Lahore and Mariana Baabar in Islamabad

Tags