"One is not sure if the military has taken a mental u-turn on Kashmir... Musharraf might be relieved if the peace process takes a pause. He can then tell the world it is India's fault."-- M. Ziauddin resident editor, Dawn

People Like Us

The aam aadmi in Pakistan is just like he is here in India. Sadly, so are the politicians.

"We reject such threats, such language. today, democratic and so-called enlightened India is hesitant about peace while we have moved on. India is not being large-hearted."-- Mushahid Hussain secretary general, PML (Q)

"Most people have no ill-will towards India. but if you blame us for everything, then why talk to us?" --Fazlur Rahman Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam

"Musharraf has invested so much power in himself, diplomacy often becomes a one-man show. After Mumbai, many were relieved the so-called composite dialogue is off." --Ayaz Amir columnist

****

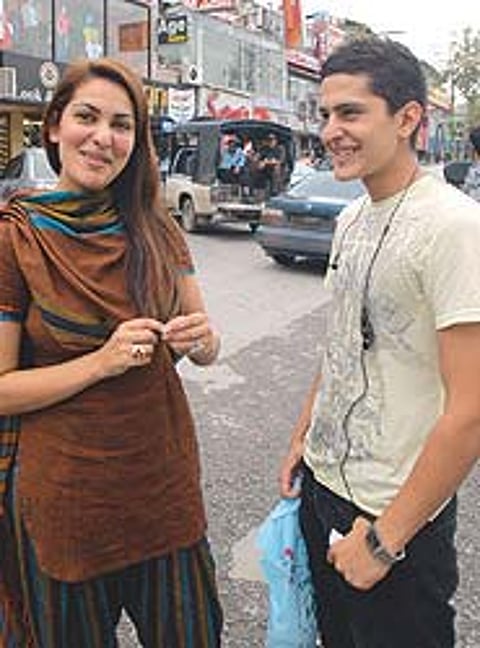

Ameen, Abdullah feel the blame game only increases tension |

In government circles in Islamabad, though, the mood is different. There's bitter disappointment that India hasn't given fresh dates for foreign secretary-level talks, a part of the peace process in which President Pervez Musharraf has invested so much. This has bolstered the belief that India is not really interested in substantive breakthroughs, remaining content with a cold peace. There are remarks about the "Chanakya" mindset of Indians, about "Hindus being too cautious" as opposed to the "straight-talking Pakistanis.

Mushahid Hussain has been a player in Pakistani politics over successive regimes, earlier as the right hand of Nawaz Sharif, now as secretary general of the ruling PML-Q (Pakistan Muslim League—Quaid-e-Azam), known as the "King's Party". He's sharply critical about the finger-pointing at Pakistan after Mumbai. "We reject such threats, even such language. It's not civil," he says, adding, "India is not Israel and Pakistan is not Lebanon." He contends that there has been a role reversal in the subcontinent. "Today, democratic and so-called enlightened India is hesitant about peace while we have moved on. India is not being large-hearted."

Dr Usman, Furqua, Khizer say bomb blasts are political |

Can Musharraf, their baap, stop them? The overwhelming view in Pakistan is that they can be squeezed but not stopped, given the current regime's limitations. As it is, Musharraf is under constant pressure from Islamists (many of whom he had nurtured before 9/11). The biggest Islamic force, the Jamaat-e-Islami, is strongly opposed to the president's stated policies to check conservatism and keep an eye on seminaries. As for the LeT, the ban on the group saw them revert to working as Jamaat-ud-Daawa, another offshoot of its parent outfit, Markaz-ud-Daawa. JuD remains under surveillance, but has been used by the state in the past to finish off Shia groups with links to Iran. Their primary purpose, though, is to wage jehad in Kashmir. Although there are links to the Afghan jehad, the LeT/JuD is an overwhelmingly Punjabi outfit, with some recruits from Kashmir and foreign countries. The "beards", as they are often referred to, have certainly managed to shift the discourse in Pakistan.

But the Islamic crew in Pakistan is a motley lot whose positions towards India vary, from extreme hate to tough-talking hypernationalism to reasonable dialogue with a neighbour with whom there are ancient links. Maulana Fazlur Rahman, leader of the Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam, is one of the more savvy clerics in the political game. He says his constituency strongly supports the peace process with India. "Most people here have no ill-will towards India. But we feel that if you blame us for everything, then why talk to us?" It is the US, not India, that is hated here, he says. "They kill people, then call them terrorists," he says, adding, "The blasts in Mumbai were against humanity. It is sad that India has succumbed to lobbies that want to sabotage peace in the region."

M. Ziauddin, the resident editor of Dawn in Islamabad, says people are very comfortable with the idea of engaging with India. But there is a growing feeling that Musharraf is getting very anxious for something concrete. "One can't be sure even today whether our military has taken a mental U-turn on Kashmir," he says. "That's why a military dictator like Pervez Musharraf has to get something in hand to say that he is not just offering concessions to India." But given the fact that India has retreated into a stony silence after the Mumbai blasts, Ziauddin believes it is not unlikely that Musharraf may, after a while, give the story another spin—I tried repeatedly, they won't talk, I give up—at least till the elections in Pakistan are concluded. "He might be relieved if the peace process takes a pause. He can then tell the world it is India's fault," he says.

Certainly, the Pakistan foreign office's tone is getting somewhat sharp. Tasneem Aslam, the spokesperson, told Outlook, "People here find it a bit incredible that the process has been put in jeopardy. The Indian government has repeatedly been embarrassed on the world stage for doing this. If Pakistan needs peace, so does India." At the same time, off the record, many commentators ask whether India really wants peace, or is there a section that is content to live in a perpetual state of antagonism. Repeatedly, I am told that a Pakistani journalist does not get far in India; I am lucky to have been given so much access. We are warm towards you; you are polite but distantly cool.

We are spending a night at Kalar Kahar in Punjab, in a lakeside rest house. There is a small tourist attraction here called the Takht-e-Babari. It is a raised platform on the edge of the lake where the founder of the Mughal dynasty, Babar, apparently rested for some days en route to India. Akhtar, a local village youth, asks whether the Babri Masjid was built by the same Babar? Yes. Why did you destroy it? I smile vaguely and say that many things get destroyed in the passing of time. But Akhtar has his own brand of wisdom: "We are peaceful here in Punjab. But so much is being destroyed in our own country. Fighting wars, growing beards. It is better to keep out of trouble in Pakistan."

Indeed, most Pakistanis see India as the fascinating Bollywood/TV soap land where women wear lush sarees and bindis and the Khan brigade runs around trees. Except for the committed Kashmir fighter, they don't have too many prejudices about their neighbour. The average villager is delighted to meet an Indian and declares himself whole-heartedly for peace. But the average policymaker in Islamabad is somewhat annoyed with what they believe is India's repeated distancing from Pakistan. They expect India to get over the "terror groups in Pakistan" incantation and grasp Musharraf's hand in a warm shake. But Indians, with their more calibrated approach to affairs of the world, may find Pakistani enthusiasm and verbosity too hot to handle, particularly after being rattled by Mumbai. A stalemate appears the safer option, though the desire for peace must linger on both sides.

Tags