His Jehad Is His Very Own

Not a Pak-Afghan-bred radical, the new Islamic warrior could be a regular American guy, swayed by Al Qaeda, but not part of it

But Faisal isn’t a lone wolf in the jehadi jungle of bearded, religious, impoverished men who dream blood. Remember Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, who tried to trigger a plastic explosive on a flight from Amsterdam to Detroit? He was a Nigerian, educated in Britain. Anwar al-Awalki secured a degree in civil engineering from Colorado State University before metamorphosing into a fire-breathing Islamic preacher. There is also the case of Nidal Malik Hasan, the US army psychiatrist who mowed down 13 soldiers at Fort Hood, Texas. And David Coleman Headley, a Pakistani-American who concealed his Muslim identity to reconnoitre for the 26/11 mayhem in Mumbai.

Add to this the list of converts. Daniel Patrick Boyd is a white American accused of leading a jehadi group in North Carolina; Bryant Neal Vinas, a Hispanic-American citizen who pleaded guilty in 2008 for assisting Al Qaeda; Dhiren Barot, a Hindu who embraced Islam of the virulent kind and was sentenced in 2006 for planning to bomb the New York Stock Exchange.

These men typify a new, bewildering pattern in global jehad—they are not devout, do not come from West Asia, do not belong to the marginalised sections and have not studied in madrassas. They are usually urbane, belong to affluent classes, have a degree from a western university and adapt easily to a western lifestyle. They’re mostly bilingual, speak fluent English and are eclectic in their reading habits, be it Islamic texts or books by western thinkers. They are also insiders, embedded in American or other western societies, a distinct break from the time Muslim militant groups were confined to Islamic countries.

What unites these new radical Islamists is that they cast themselves in the mould of avengers, burning with the zeal to punish the US, its western allies, and even those countries where they feel Muslims are oppressed—like Russia or Israel. Their desire for vengeance doesn’t exclude Muslim countries or their governments supporting the exploitative West—like Saudi Arabia and Pakistan.

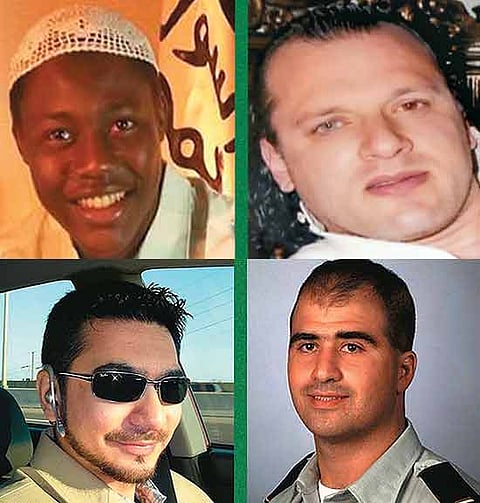

Clockwise from top left: Farouk Abdulmutallab, David Coleman Headley, Nidal Malik Hasan, Faisal Shahzad

Who they are, whom they oppose

- Al Qaeda is now more a state of mind than a formidable terror organisation. A state of mind shared by those Muslims who believe in violently opposing what they perceive as the injustices of the world.

- Primarily directed against the West, particularly the United States. But it is also aimed against those countries seen to be oppressing Muslims—Russia, Israel and India, for example.

- Willing to target Muslim countries aligned to the West or fighting Muslim terror—Saudi Arabia, Egypt, even Pakistan.

- Theirs is a war without boundaries—any country which is frequented by westerners, for instance, is considered a legitimate enough target.

What they seek to achieve

- No longer aims at establishing Islamic states. But wants a just world order, for Muslims and non-Muslims alike.

- Its anti-West agenda has been expanded to include the politics of environment. Osama bin Laden's last speech accused the West of damaging environment.

- It's also opposing globalisation, portraying it as a ploy of the developed world to exploit underdeveloped nations.

- Primary impulse is to weaken sole superpower. All other changes will ensue on their own.

- Become an umbrella group for other militant groups fighting different governments. Provide moral support and ideological justification for violent action.

How the new recruit is different

- He's a Muslim living in western societies. Also in non-western countries where Muslims nurse grievances.

- Belongs to affluent, educated families, often a product of Western educational institutes.

- Bilingual. English is the preferred language of global jehad.

- Voracious reader. Sources info from Islamic literature and doctrines, and from western philosophers and political figures.

- Not religious. Adapted to western lifestyle, drinks, gambles, even has white partners.

- Gets indoctrinated through the net. Downloads bomb-making manuals. Or, if he can, heads to Pakistan's badlands or Yemen.

***

| “To get radicalised, one doesn’t have to go to a madrassa or a training camp in the Pak-Afghan badlands. Internet chatrooms are good enough.” Abdul Bari Atwan, Editor, Al Quds al Arabia, London |

| “They (the new radicals) are outliers, who can cause massive damage and get massive response. But they don’t belong to one group or movement.” Faisal Devji, Author, ‘Landscape of the Jehad’ |

| “Such dichotomisation (Islam vs the West) overlooks the actual nature of the conflict, which is not about religion or culture, but about politics.” Cassandra Balchin, Women Living Under Muslim Law | ||||

| “Morocco, Indonesia and Pakistan promised to be democratic but did not deliver. A class revolution in slow motion is taking place here.” Akbar Ahmed, American University, Washington |

| “When it comes to other religions, we can tease religion out of politics. For Islam, we have blinkers on. Isn’t the BJP’s rise more about politics?” Deniz Kandiyoti, SOAS, London |

| The growth of non-state actors coincided with “a new era where many regimes lost the control they once had over territory and people”. Abdul Wahab al-Effendi, Sudanese commentator | ||||

|

-- John L. Esposito, Georgetown University, Washington

***

- May 1, 2010: Faisal Shahzad, a 30-year-old Pakistan-born naturalised American, attempts a bombing at the Times Square in New York

- Mar 29, 2010: At least 40 people killed and over 100 injured in suicide bombings carried out by two women at two stations of the Moscow metro. Islamist Chechen separatists claim responsibility.

- Dec 25, 2009: Farouk Abdulmutallab, a Britain-educated Nigerian, tries to detonate plastic explosives hidden in his underwear during a flight from Amsterdam to Detroit

- Dec 9, 2009: Five Muslim-Americans from northern Virginia (three Pak-Americans, two of African descent) arrested in Sargodha in Pakistan on their way to North Waziristan for training to fight in Afghanistan

- Nov 5, 2009: US Army Major Nidal Malik ‘AbduWali’ Hasan, whose parents had emigrated to the US from Jordan, opens fire in the Soldier Readiness Center in Fort Hood, Texas, killing 13 people and wounding 30.

- Nov 26, 2008: David Headley, formerly known as Daood Sayed Gilani, a Chicago-based Pakistani-American, reconnoitres targets in commercial capital Mumbai for the Lashkar-e-Toiba

- Oct 12, 2009: A Milan resident of Libyan descent, Mohamed Game, tries to take a bomb into police barracks in Milan but lets it off at the entrance when he sees guards pointing guns at him

- Jun 1, 2009: Angry over US troops killing Muslims in Afghanistan and Iraq, American-Muslim convert Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad opens fire at a US army recruiting office in Little Rock, Arkansas

- Jun 30, 2007: Bilal Abdullah, a British-born doc of Iraqi descent, and Bangalore-born engineer Kafeel Ahmed drive an SUV loaded with petrol containers and propane gas canisters into the Glasgow Intll Airport

- Mar 3, 2006: Iranian-born American Mohammed Reza Taheri-azar drives an SUV into pedestrians at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, to "avenge the deaths of Muslims worldwide"

- Jul 7, 2005: Four Muslim men, three of British Pakistani and one of British-Jamaican descent, launch four suicide attacks on London’s public transport system. Fifty-two others killed and around 700 injured.

- Nov 2, 2004: Dutch-Moroccan Mohammed Bouyeri stabs and shoots dead Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh, who made a film on violence against women in Islamic societies, in Amsterdam

- Mar 11, 2004: A loose group of Moroccans, Syrians and Algerian-Muslims held responsible for the series of bombings in the Madrid commuter train system which kills 191 and wounds over 1,800 people

***

Recent research has tried to understand the roots of the radicalisation of these men who live far away from the cradle of jehad. Olivier Roy, the French author of Globalised Islam: The Search for a New Ummah, says these men, often unhappy or unsuccessful in the West, discover the ‘enemy’ through the internet—a virtual Babel of Muslim angst articulated by clerics and containing selective images of oppression of their brethren by the US. They become members of the virtual ummah (community) and experience its sorrows—the personal becomes fused with the public. Wishing to escape their unhappy lives, they seek redemption through ‘heroic’ acts against the perceived enemy (the West). As Abdul Bari Atwan, the London-based editor of the Al Quds al Arabia newspaper, told Outlook, “To get radicalised, one does not necessarily have to go to a madrassa or a training camp in the badlands of the Pakistan-Afghanistan borders. Chat rooms and literature on the internet are good enough for radicalisation.”

Once radicalised through the net, the would-be militant chooses his method of retribution: he either travels to the badlands of Pakistan, Yemen or Afghanistan for training, or just downloads manuals on bomb-making. He’s now the armed avenger. But Al Qaeda still has a role to play. With its ability to mastermind spectacular attacks impaired, Al Qaeda has consciously chosen to become a state of mind. Osama bin Laden’s videotapes are supposed to inspire radical Muslims and provide a moral framework for the avengers to justify their violent action. Oxford University’s Faisal Devji, author of Landscape of the Jehad, told Outlook, “They are outliers, who can cause massive damage and evoke an equally massive military response. But they’re simply not connected to any particular movement or group.”

Devji says that unlike Hamas or Hezbollah, Al Qaeda’s agenda doesn’t have a closure, a fixed goal to achieve—the creation of an Islamic state, for instance. As he explains, “The actions of Al Qaeda seem to have departed from that intentionality, making these more symbolic and ethical acts.” So what then is the agenda of Al Qaeda?

It is definitely aimed against the US and its policies, particularly the presence of its troops in Iraq and Afghanistan. As more people die in these countries from US attacks, it hopes to deepen the resentment against the superpower. To win popular support, it harps on the American hypocrisy of condoning Israel’s treatment of Muslims. Recently, however, Al Qaeda’s agenda has expanded to include the cutting-edge issues of politics: environment and globalisation. In his last few public pronouncements, Osama has accused the West of polluting the world, of resorting to globalisation to exploit the underdeveloped world. Experts feel he did this to appeal to those sections which have converted to Islam, or are secular Muslims who can’t hitch themselves to an exclusive Islamic agenda.

The world can change, argues Al Qaeda, only if the West, particularly America, is brought down to its knees. This idea was mooted in the late ’90s by Osama’s deputy, Ayman al-Zawahiri, who cited the close link between the collapse of the Soviet empire to its defeat in Afghanistan. If one superpower could be defeated, he argued, why not the US?

To fight the US, though, Al Qaeda had to first transform itself into a global organisation. It did this through the twin attacks on the US embassies in Nairobi and Dar-es-Salaam in 1998, integrating it at once into the global security regime administered by America. With 9/11, the group carved out a space for Islam in the West. Till then, no other Islamic group had managed to win for either their jehad or Islam a globalised status. The Quran jumped into the New York Times bestseller list, prompting Devji to say, “It’s ironical that the threat of Islam was the only thing that made possible its recognition as a religion of peace.”

It’s indeed a religion of peace, insists John L. Esposito of Georgetown University, Washington, quoting Quranic verses to point to the extensive limits placed on the use of violence. “Islam rejects terrorism, hijackings, and hostage-taking,” Esposito told Outlook. “However, Muslims are permitted, indeed at times required, to defend their religion, their families and the Islamic community from aggression.” Citing Pew and Gallup surveys to stress that “there’s no conflict between Islam and the West”, Esposito does admit that some Muslims are profoundly affected by US policies. “The perception of occupation and injustice in Iraq, Afghanistan, Kashmir, Chechnya and Palestine continues to be a catalyst heavily exploited in the rhetoric and ideologies of terrorist organisations,” he argues.

Radical Islam is closely linked to the evolution of Muslim countries post-World War II, says Akbar Ahmed of American University, Washington. As he told Outlook, “Countries like Morocco, Indonesia or Pakistan all promised to be democratic and progressive states when they got their independence, but they failed to deliver.” Rampant corruption, lack of development or absence of fundamental rights angered the Muslims, more so because Islam has a strong undertone of social justice. “A class revolution in slow motion is taking place in many of these countries,” Ahmed argues.

But thwarting this class revolution has been the US, which has brazenly supported regressive Islamic regimes. Says Gilbert Achcar, a Lebanese who teaches at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), London, “Progressive regimes in the Muslim world have been fought and destroyed by the US.” He cites the example of Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser, whose policies compelled the Muslim Brotherhood to flee to Saudi Arabia. There, the brotherhood was nurtured by the Saudi rulers and the CIA to fight the Nasser government, which had grown independent of the US.

The West bolstered regressive regimes also because their opponents, mostly secular leftists, drew their inspiration from the Soviet Union. The collapse of the USSR gave despotic regimes the opportunity to crush their Leftist opponents. Denied a secular platform, the dissenters turned to the mosque to articulate their grievances, aware that even a ruthless ruler must exercise caution in attacking religious institutions. Not only did religion and politics mingle, but it also paved the way for non-state actors to emerge. Initially, these non-state actors, as in any society, opposed the nation-state in which they lived. But the successful jehad in Afghanistan turned these non-state actors into international players who were willing to pool their resources to combat oppressive regimes and their supporters in the West.

The growth of non-state actors, says Sudanese commentator Abdul Wahab al-Effendi, coincided with “a new era where many of the regimes no longer have the control they had over the territory and the people”. He cites the example of Pakistan which once deployed non-state actors to wage battles across the border, but is now not strong enough to prevent them from setting their own agenda directed against India, the US, and even Islamabad itself. He, however, cautions against clubbing all these non-state Islamic actors under one category, pointing to sharp contradictions among them. “For instance, those who constituted the Northern Alliance are not unhappy with the presence of US troops in Afghanistan,” al-Effendi told Outlook.

Cassandra Balchin of Women Living under Muslim Law, an international campaign group, too says pat categorisation such as Islam vs the West (or Islam vs the world) are inherently flawed. After all, she argues, a large number of Muslims are ‘westerners’ and include both white British and Black Americans. “Such dichotomisation overlooks the actual nature of the conflict which is not about religion or culture, but about politics,” Cassandra told Outlook. Agrees Deniz Kandiyoti of SOAS, “When it comes to other religions, we are able to tease out the religious aspect from politics. But when it comes to Islam, somehow we have our blinkers on. Take the BJP in your own country. Isn’t its rise more about politics than religion?”

Obviously, Islam isn’t a monolith, riven as it is with a variety of thoughts, customs, traditions and lifestyles. Most experts, however, agree that radical Islam and its poster-boy, Osama bin Laden, have appropriated Islam to mobilise people in their political battle against corrupt Muslim regimes and their western supporters. And because of their spectacular attacks and headline-grabbing rhetoric, they’ve erroneously become the face of Islam that the West perceives, understands and fears so much.

The battle against radical Islam is complicated. With Al Qaeda stressing on ethical issues to justify its acts of violence, many desperate Muslims in the West and elsewhere are likely to find their inspiration and redemption in jehad. The West, in turn, is likely to strengthen its already stifling security apparatus at the cost of eroding ideas it is associated with: of freedom of speech, expression and free movement. Curtailment of these rights would be akin to an Al Qaeda win. The West is also expected to intensify the war on terror—and the ensuing bloodshed will only help bolster the Al Qaeda campaign. The best way out for Washington is to resolve the Palestine-Israel issue and cease supporting discredited Muslim regimes.

Tags