All the 26 computers in the room have over two boys working efficiently on them. Last year several Pentium 3 PCs were upgraded to Pentium 4. Here the boys are taught Windows applications, web designing, hardware engineering and elementary programming languages like BASIC. Pakistan President General Pervez Musharraf may point to this scenario and say that he has won a crucial battle. He may not be right.

"We realised the importance of computers from within even before Musharraf came to power," says Naeemi. Jamia Naimia may have computers but it has not included maths or general science in its courses, which was an explicitly stated wish of the president. About two years ago, in a controversial televised address to the nation, Musharraf asked madrassas to change and step into modern times. "He was influenced by the paranoid Americans," Naeemi says with rage, "and the dollars that they were willing to give him."

In a decree that has come to be known as the Madrassa Ordinance, Musharraf laid out a plan. Among the over 12,000 madrassas that teach over 1.5 million students, he decided to choose 8,000 and spend over $115 million on influencing them to include English, maths and the sciences along with religious studies in their curriculum. He asked them to register as legitimate institutions of learning and lay open the sources of their funding.

"He had three objectives," says Shahzad Qaiser, a former secretary of education for the state of Punjab and a civil servant who today is a faculty advisor of a research body that studies madrassa education. "He wanted to eliminate militancy from the madrassas, wanted them to stand for Pakistan first instead of supporting extremist foreigners from the Middle East, and more importantly, modernise. About the first two demands, the scholars of the madrassas responded by denying that they ever hosted any activity that they considered illegal. About the third demand—to modernise—they said that what is right and what's wrong cannot be imposed on them. That's the status even today."

Binary Fission

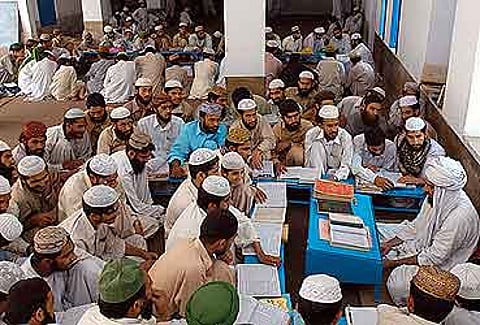

Computers are but a false illusion of the modernity Musharraf wants in Pakistan's madrassas

Faced with widespread resistance, Musharraf started implementing the unwritten bit of the ordinance."Police raid madrassas even today," says Mohammed Riaz Durrani who runs a small madrassa in Lahore. "They arrest some students saying they are foreigners with no valid visas. Government auditors visit the madrassas and ask for their accounts. Industrialists who donate money to madrassas are harassed. Those donation boxes that used to be kept in shops and street corners have been removed. All this has only strengthened the resolve of the scholars to stand firm and resist." Two years after Musharraf declared his policy war on the traditional schools, very few have heeded and even refuse to admit that the president had anything to do with the change.

Jamia Ashrafia is a place that the general may call a model madrassa. There is an audio-visual presentation in English under way that stresses proudly on "the utilisation of modern information technology for effective communication of the Islamic message to mankind all over the world". Principal S.M. Rafi is sitting near the projector and interrupting the voiceover to excitedly state that the pages on the computer can be turned "just by a click". This academic year, Ashrafia will include maths and general science in its primary and secondary syllabus for its 1,500 students. This month it got a consignment of 50 personal computers. "We can't name the donor," principal Rafi says but a top bureaucrat insists, "the computers have come from the government". Ashrafia is willing to change with the times but it doesn't want to admit that the government has forced it to. "They don't want to appear as though they have been bought over," the bureaucrat points out. Those who dislike Musharraf say that two years after he began cajoling and arm-twisting madrassas, places like Ashrafia are just a handful. And so he has failed. Optimists say that the first rays of a new dawn have arrived.

Computers are often a convenient mask of obtuse modernity that only aid the meaningless declarations of progress as e-governance ventures of various Indian state governments have repeatedly shown. "But madrassas have genuinely discovered the usefulness of computers," says Tahir Hameed Tanoli who has done a doctoral thesis on the psychology of Muslims. "It is not a cosmetic change." What the madrassas resist is the blind plunge into modernity. "Instead of quantum leaps," Tanoli says, "the scholars want to change like the night becomes day. Slowly."

The government of Pakistan has always emphasised that it does not plan to replace Islamic education in madrassas with modern streams. The idea is to make the two coexist because the importance given to Islamic education, even among the elite of Pakistan and its displaced citizens, can never be underestimated.

Seventeen-year-old Touseef Hussain from Birmingham, with artistically modified sideburns, is an unlikely candidate to learn the Quran. But for the last seven months he has been learning the holy book in Lahore's Minhaj-ul-Quran, an institute that teaches religious topics along with what are called modern subjects. Though it is popularly described as a very modern madrassa, Minhaj-ul-Quran aggressively distances itself from the feared word. As an administrative official states, "You can call us a school." With Hussain is 21-year-old Rehan Ahmed from Scotland. He was doing his mechanical engineering in that country when he, "on my own will", decided to study Islam in Pakistan. He has spent over two years in Minhaj-ul-Quran and will spend one more year before he returns to mechanical engineering.

Large urban madrassas in the pangs of a new introspection are not truly representative of the madrassa culture in Pakistan. In states like the North West Frontier Province and Baluchistan, several madrassas do not have a roof, the ulema and the students go hungry on bad days."They resist modernity because they don't know how it's going to help them. It's in such places that the framework of militant training still exists," says madrassa education advisor Shahzad Qaiser. "After Zia-ul-Haq made madrassas a hate factory to generate young men who will go fight the Russians for America, most of them are a bit lost and angry today without government patronage. Suddenly they have been told they were wrong, very wrong, they have to change and become good people." Even in the liberal madrassas of Lahore, the aftershocks of the pursuit of hate have not abated. That's why 15-year-old Amjad Shahzad who wants to become a software engineer stands outside Jamia Naimia's neatly carpeted computer department and says with conviction, "I will war against India." And principal Sarfraz Naeemi claps gleefully.

Tags