A Barsati In Beijing

It's <I>Awaara</i> that endures, not 1962. Hindi-Chini bhai bhai, it seems, is neither myth nor cliche.

- About 1,000 Indian households, with family or single, live and work in Beijing

- Last year, 6,000 Indian students, mostly medicos, were enrolled in universities

- The Indian in the Chinese mind is still defined by Bollywood

- What Indians like about China: security, business ethos, determination, discipline

- The problems Indians face: language barrier, cuisine with dog, donkey meat

- What the Chinese admire about Indians: IT, English language skills

- What they dislike about Indians: their lack of punctuality

***

All the same, the absence of conviviality in India, in contrast to the carnivalesque feel of its films, didn't diminish Zheng's love for Pastakia: they married on their return to Beijing, where they own The Taj Pavilion that serves spicy Indian dishes to the growing expatriate population unable to appreciate Chinese cuisine with its dog and donkey meat.

As China achieves a prosperity worthy of a superpower and redefines its relationship with the world, the good old Indian settled here is often surprised to discover the Chinese people impose an identity on him rooted in Bollywood. This is what Pawan Kumar, who manages the Chingari restaurant in Beijing, realised on a train journey from Beijing to a port town in the east. He became the centre of attraction as soon as the fellow travellers learnt that he was from India. "They all gathered around and sang Awaara Hoon... to me," Kumar remembers. During the fortnight of Olympics, I met at least three elderly men who insisted on singing that memorable Mukesh song to me.

Melody girl: Hou Wei sings Hindi songs at the Chingari restaurant |

Centuries before Bollywood mesmerised the Chinese, the relationship between the two nations on either side of the Himalayas was forged because of the travels of Chinese sages into ancient India. It was bolstered further during the heady days of anti-colonial movements and Third World solidarity, epitomised by the Hindi-Chini bhai bhai slogan. And then, in 1962, occurred the Sino-India confrontation, engendering years of bitterness, suspicion and hostility.

But today's China is changing—and not just economically. Gone is its ancient insularity; its suspicion of the alien evangelist/trader is tempered by solid business sense. Business is no longer considered anti-people. The insatiable desire for wealth has become a drug potent enough to induce amnesia. No wonder, R.K. Singh, who's been living and working in China for over 10 years, has never met a Chinese who's quizzed him about the problems the two nations have had. "The average Chinese has moved on, he's interested in what we can do today, not what happened in the past," Singh says.

Even the contentious Tibet issue, the presence of the Tibetan government-in-exile in Dharamshala, hasn't provoked the Chinese to direct xenophobic passion against the Indian. "They don't like their politics to be interfered with and they don't like someone to criticise their government. But we as Indians have not had any incidents because of Tibet," says Singh, who's the president of what informally has been organised as the Indian Community in Beijing.

Indeed, Tibet didn't dog me on my walks on the streets of Beijing. Instead, young artists—mostly girls, for some reason—struck up a conversation with me in halting English, professing their admiration for India. In their studios are stacks of painting they attempt to hawk, willing to bargain and amenable to heavy price reductions. And though communication for business purposes is often conducted through pantomime, most Indians here rate language the biggest problem they encounter in Beijing. (There are roughly 1,000 Indian households—with families or single in the capital city.)

"It's the biggest hurdle you face here as very few people can understand English," says Saurav Anand, who heads the marketing division of Ashapura Minechem Ltd in Beijing. "And we're better off in Beijing.... In the remote regions, it's a still bigger problem." Those who've been living in China for some time have learnt the intricate Mandarin language enough to communicate. "One must learn the language," says Singh, "for it's essential to get by, and also to let the people know that you're trying to adapt, not keeping yourself out totally."

The other problem the Indian faces is food. Not only are the Chinese fond of dog and donkey meat, in some regions, food is served with the head still attached to, say, the rest of the lamb. For desi meat-eaters, the sight isn't appetising; for vegetarians, it's simply revolting. The plight of Indians who came to China on assignment inspired Laxman Hemnani, who works for Aptech, to start a restaurant. "They'd work without a complaint," Hemnani says. "Food is all they'd ask for."

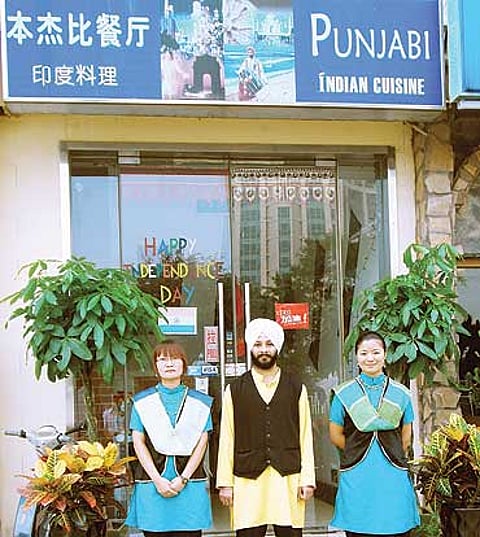

Hemnani's tony Ganges restaurant has three outlets, and the Taj Pavilion has two, besides at least 13 other major Indian eateries. But these aren't patronised by the Chinese who consider Indian food very hot. Hemnani says most of their customers are expatriates—South Asian and European. "Clearly, the market is still growing," he adds.

Indians, particularly women, are also enamoured of the security Beijing offers. Though some observers say that the city is not crime-free (only the authorities don't allow it to be reported, it's alleged), on the streets of Beijing, past midnight, you can see women walking around without anyone bothering them. Hou Wei dances and sings Hindi songs in the Chingari restaurant, and often has to return home late at night. She says she has never been bothered by anyone. "Sure, in the bus or the subway, someone might paw you, but it's very rare," she says. "You have the security of knowing that if there's a problem, there's always a cop not far away."

Indian students—most studying medicine, they numbered around 6,000 last year—who've been living in China agree. Sonam Kaushika of Delhi, a medical student in Tianjin near Beijing, has been in China for three years, and not once has she faced the kind of problems a Delhi girl would face daily. "I feel more secure in China than Delhi."

Aren't the Chinese enamoured of things Indian—other than its film, that is? India's progress in information technology has impressed the Chinese. "They have respect for India, because their own wise men in the past came to India to seek knowledge," says Hemnani "But they also believe that apart from IT, India is not really too developed in terms of technology and infrastructure." They also envy the English language skills of Indians. What they don't admire about Indians is their lack of punctuality. "Which is true, having seen people here and comparing them with my Indian colleagues, who are never on time," says Anand.

The Chinese people and intellectuals express the hope that the contentious issues between the two countries, particularly the festering border problem, would be resolved with time. "I'm sure things will get better," says Jiang Jingkui, vice-director of Centre for India Studies and a Hindi professor. "We've had trust and a good relationship for centuries—the conflict (1962) happened in one single year. One bad year cannot undo our ties."

Must the world fear China's economic might and its ambitions? Jiang ponders over the problem and answers, in Hindi: "The West is afraid because they fear we also will do what they did around the world—they went for business and then brought in their armies. China has no such plans. We are only trying to create opportunities for our own people. The world need not fear us." Jiang says Chinese sages in ancient times went to India and returned with a faith. He says the two countries must again work with faith and trust, because "we're natural allies". And Indians in Beijing agree, saying the time could be ripe for a truly enduring relationship.

Tags