Fade-In To the World

A growing market for the best cinema finds a supply

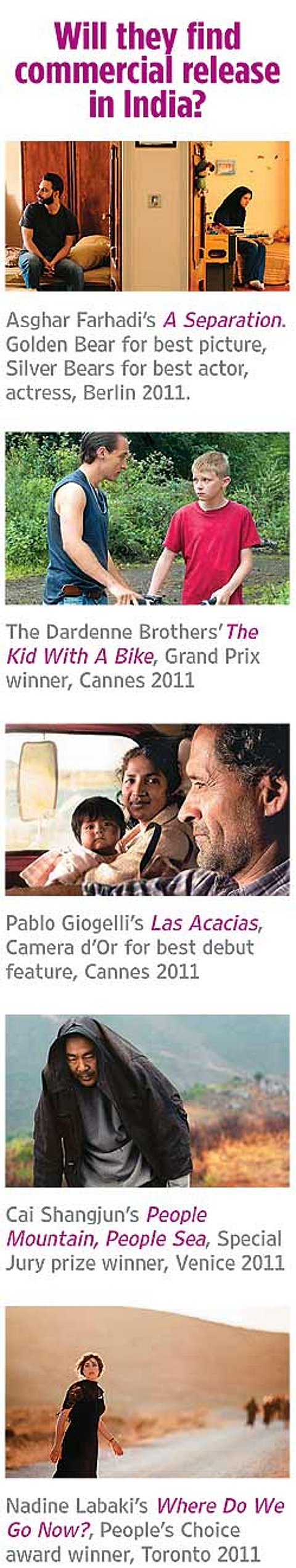

When cine buffs clamour for such films at festivals, why doesn’t this enthusiasm translate into their commercial success in India? Why is it still rare to find Nanni Moretti’s Habemus Papam running alongside George Clooney starrer Ides of March or Imtiaz Ali’s Rockstar in multiplexes? Why are these films viewed only at exclusive clubs, esoteric festivals or on specialist TV channels? Or, clandestinely, via pirated DVDs or downloads? Will world cinema ever find space in mainstream multiplexes? To be fair, there have been some successes: Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s The Lives of Others (German), an Oscar winner, ran in eight cinemas in Mumbai and Pune for three weeks with 80 per cent occupancy, till then unheard of. Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (French) and Nadine Labaki’s Caramel (Arabic), too, brought in 70 per cent collections. But these successes are exceptions—despite the consensus that a committed audience for world cinema does exist in the country.

“There’s certainly an audience in the metros and amongst the new generation Indians that wants more than Dabangg and Bodyguard,” says Deborah Benattar, audio-visual attache at the French embassy. Access and exposure to world culture is better, people are travelling a lot more and are more receptive to other societies. Numerous film festivals have been creating a groundswell. The internet has been the other game-changer. “The younger generation is net-savvy and has less compunctions about piracy issues. They are accessing world cinema online,” says Amit Khanna, chairman, Reliance Entertainment. And Parin Mirani, senior executive, Reliance Home Video, says, “There’s demand for and queries about world cinema titles.”

But the numbers still don’t add up. “It’s a growing market, but not large enough to warrant commercial releases,” says Khanna. Even if a world cinema title is released at just one screen or show in a metro, it needs at least 50,000 viewers to break even. The few thousands who throng film festivals are not enough to make world movies commercially viable. Another pointer is the home video sales of these films. For every 1,000 Hollywood DVDs bought at Reliance Home Video, only 300 of Spanish, Iranian or Korean films find takers. “It’s a limited but evolving market,” says Shiladitya Bora, film festival and alternate programming specialist with multiplex chain PVR Ltd.

There are other pitfalls. The cost of acquiring foreign films remains prohibitive. Add to that the large ad-spend. No wonder only two French movies released in India in the recent past: From Paris with Love, produced by Luc Besson, and Abel Ferry’s Vertigo. The release of The Artist assumes interest in this light. Its India rights were bought in Cannes earlier this year. “We are keeping our fingers crossed,” says Benattar.

The Indian censorship system is another culprit. There wasn’t much left of Alejandro Gonsalez Inarritu’s Biutiful after the censors were through. “It felt very disjointed,” remembers Sanjeev Kumar Bijli, joint MD, PVR Ltd. “It could only do business of Rs 4-5 lakh. Rs 4 lakh is spent in just print and publicity alone.” Similarly, innumerable edits were suggested in Federico Fellini’s Amarcord, so much so that a home video company decided not to release it in India. No wonder, in the last couple of years, many enterprises aimed at bringing world cinema to India had to shut shop, like Palador and NDTV Lumiere. “Only films that have won awards and gathered acclaim manage to work in India,” says Bijli.

But PVR eyes an opportunity. The people who brought the multiplex trend to India have now decided to address world cinema viewers with Director’s Cut, a plush new property at a mall in Delhi’s Vasant Kunj area. It’s got the works—Jean Luc Godard posters on the wall, imagery from Akira Kurosawa’s works on cutlery and menu cards, biographies of Pedro Almodovar and David Lynch on the shelves. With its cafe, restaurant, store and luxe theatres, Director’s Cut is a celebration of world cinema, besides Bollywood and Hollywood. With another initiative, Director’s Rare, PVR aims to get serious with alternative programming. It will include acclaimed films from across the globe, including Indian indie films and regional cinema, masterpieces from iconic filmmakers and of course the latest from the festival circuit.

But won’t the high ticket prices—Rs 600-1,000 at Director’s Cut—keep students, a keen audience, away? Bijli has plans for them too. “Once a new movie from the festivals is released at PVR Director’s Cut, it will also travel to select PVR properties,” he says. A Martin Scorsese festival is set for this month; also on the cards is an international film festival in Delhi.

After success with their Mumbai Film Festival, PVR is in talks with the producers of some world movies to bring them to India. So we may soon see Bela Tarr’s Turin Horse, Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia, Na Hong-jin’s The Yellow Sea, Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once Upon A Time in Anatolia and Alexander Sokurov’s Faust.

Meanwhile, Bombay-based Taj Enlighten, the country’s largest film society, is going aggressive: it inaugurated its Delhi chapter last weekend. Plans are to screen two films every weekend, and over a hundred ‘essential’ films over the year. Film lovers can enroll for an annual fee of Rs 2,000 or Rs 1,000 for six months. The society kicks off with Christopher Doyle’s Away With Words and Mel Brooks’s The Producers. So if you’ve had an overdose of Bodyguards and Singhams, and think it is time to rebalance your senses, do go out and watch an Asghar Farhadi or a Hazanavicius.

Tags