On a typically salubrious evening in the Russian capital this month, the city’s elite clinks champagne flutes on the art-peppered lawns of the Moscow Museum of Modern Art. The cynosure of all eyes is a diminutive man. His name: Steve McCurry. As a world-famous photojournalist, the American is best known for ‘The Afghan Girl’—a captivating still of an Afghan-Pashtun orphan with her piercing green eyes that rocked the world as the cover of an issue of the National Geographic magazine in 1985. McCurry was 35 then.

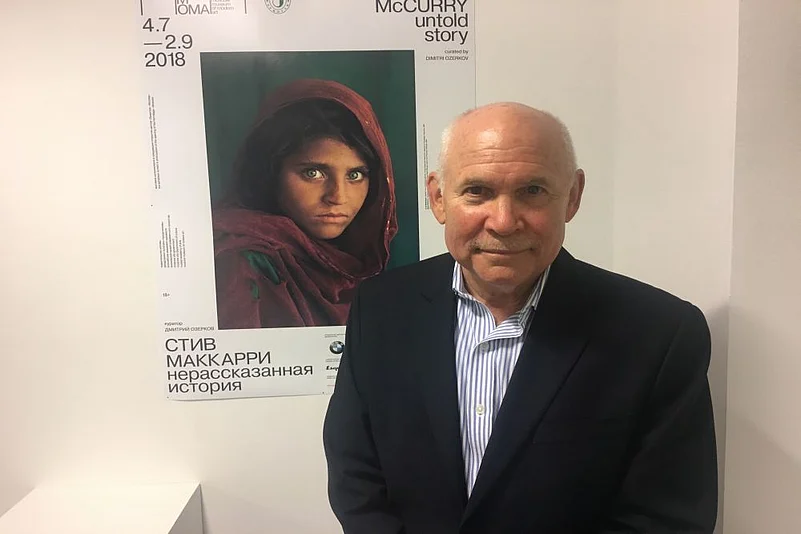

Today, the image-maker is at MMOMA on 10, Gogolevsky Boulevard. At the inaugural of his latest exhibition titled ‘The Untold Story’, he is dressed in a striped blue shirt, grey trousers and black blazer. It’s a highly anticipated show. Flashbulbs pop, as the celebrity lensman—flanked by MMOMA director Vasili Tsereteli and acclaimed Russian sculptor Zurab Tsereteli who is president of the Russian Academy of Arts—faces a phalanx of photographers. Guests queue up to pump flesh (or take the obligatory selfie), while correspondents (like yours truly), wait for a chance to interview a man whose oeuvre has propelled him into the orbit of all-time greats.

Advertisement

‘The Untold Story’ is a collection of 85 works which curator Dimitri Ozerkov tells me was culled over two years from a gargantuan collection. The event offers an insight into 68-year-old McCurry's artistic language that amalgamates a reporter's approach with a photographer’s empathy towards his subjects. It also explains why more than a reporter/photojournalist, McCurry prefers to call himself an ‘observer’ or ‘storyteller’.

(Sharbat Gula, Afghan Girl. Peshawar, Pakistan, 1984. © Steve McCurry)

Each image at the two-month-long exhibition ending onSeptember 2 possesses a rare and powerful intensity that imprints itself in the viewer’s mind indelibly. Vignettes from India, too, do come—in strong torrents: often rain-soaked, as the vast Asian country is now what with monsoons having covered its entire expanse. There are Rajasthani women huddled under a tree as a sandstorm whips up around them, a flower-seller on a glutinous Dal Lake in Kashmir’s Srinagar…. On another mountainous location further east of the Himalayas shows a pilgrim—in Drango Monastery of Kham in Tibet.

Advertisement

Though part of a larger narrative—each photo is a remarkable standalone portrayal that helps one understand why McCurry’s art occupies an exalted place in the tradition of 20th-century photography. An intrepid career spanning over three decades has yielded poignant, riveting snapshots from scores of geographies—the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, images from Beirut, Cambodia, the Philippines, the Gulf War, the former Yugoslavia....

Then there are photographs produced during his trips to Myanmar, Indonesia and Sri Lanka, many of them documenting the lives of Buddhist monks. McCurry’s vibrantly joyous images that capture the way India celebrates events are reinforced by his books on the country, including Monsoonand Steve McCurry: India.

(Dust Storm. Rajasthan, India, 1983. © Steve McCurry)

However, for the acclaimed chronicler, the photos at the Moscow exhibition are the “most important ones” in his career. “These are the places and human states that seem to me the most significant,” he says. “They show the story about people and life around the world, and my unfinished visual diary. They represent places and people that I’ve met that explain why I spent my time travelling and exploring the world we live in.”

Along with photographs, the exhibition also showcases fragments from the lensman’s notebooks, his travel itineraries and archive material hitherto unveiled publicly. One of his travelling notebooks contains a simple mantra for a successful shot: ‘You have to get into the water to make good pictures’.

Advertisement

It is a motto that has defined McCurry's career. He has leveraged the most traditional form of photography (portraiture) to capture unique geographies, the planet’s diversity and its cultural wealth. It also makes him one of the most important voices in contemporary photography. Today, McCurry has over a dozen books besides countless magazine/book covers and exhibitions to his credit. “My camera is my passport,” he said famously. He carries it wherever he goes.

(Portrait Photographer. Kabul, Afghanistan, 1992. © Steve McCurry)

McCurry carried it to India in 1978. Never mind if he has visited the country over 80 times. What appeals most to him about the nation of 1.3 billion people? “India's cultural richness fascinates me with its many different religions,” he explains. “It is so vast, but somehow it works and the people still find a common identity. I never will tire of India’s rich and varied culture and geography, and its exuberant, celebratory spirit—in those senses, you cannot find another country that compares. I still feel I have barely scratched the surface of Indian culture and, to this day I am drawn to return there once or twice a year. If I had to choose just one country to live my life in, it would be India.”

Advertisement

Making India his base, McCurry also forayed into Pakistan and Afghanistan in the 1980s, freelancing for leading international dailies and weeklies. War-ravaged Afghanistan was where he returned decade after decade. Starting from the time when Soviet Red Army was fighting ferociously with the Mujahideen and city after Afghan city was being pulverised by relentless mortar-shelling. The refugee camps that peppered the Afghan-Pakistan border brimmed with tragic human stories. McCurry got to work in this violent and virulent landscape chronicling stories of hope and survival.

(Waiters exchange trays across a train in Lahore, Pakistan. Photo Neeta Lal)

In fact, McCurry was the first to record the Afghan conflict, the coverage of which at that time was censored both in the USA and Soviet Union. He opines that war brings out people’s true nature, the best and worst, when it is a matter of life and death. “I was in Afghanistan during some of the worst bombings that went on constantly day and night,” recalls the photographer. “After a couple of close calls with bombs and mortar rounds, you start you feel like your number may be up any time.”

Advertisement

So what attracted him to conflict-ridden regions? “I think when you’re young, you are more willing to take risk to tell these important stories. There is also a drive in some people to want to be in the front line of a certain story—it compels them to want to witness these stories firsthand. These people want to run towards a situation that others are rushing away from. Although I try to be careful and only take calculated risks. I have learned so much about human behaviour through my visits to conflict zones and observing people fighting for fundamental things like their family or country.”

Advertisement

Some assignments proved near-fatal. “Once,” recalls the photographer, “I was almost killed in Yugoslavia in 1989.” McCurry had hired a tiny ultra-light plane to do aerials when the pilot swooped down to the surface of the lake, so close that it made his heart sink.

(A tailor wades through monsoonal waters in Porbundar, Gujarat. Photo: Neeta Lal)

“The pilot was trying to show off, I suppose. It was too late and the wheels got caught in the water. As soon as propeller hit the water, it was destroyed and the plane flipped upside down, trapping us. The plane sank into the icy lake,” says McCurry. “I was stuck in an open cockpit by a makeshift seatbelt and, when I realised I was about to die, my instincts kicked in and I slid down underneath the seatbelt and made it out to the surface. The pilot was fine and never even tried to help me. It was bizarre!”

Advertisement

Does the photographer feel that the current era—defined by less risk-taking, iPhone wielders and digital technology—is undermining the romance of old-style photography? “Right now,” says McCurry, “I use a Nikon D850. But the camera you use isn’t important. That being said, digital photography has come a very long way and I find it to be superior to film—it is more flexible and you can work in lower light. I have used different film and digital cameras over my career, but I try to carry a minimal amount of equipment, one or two lenses, to avoid drawing attention.”

Ever the globetrotter, McCurry says he’s currently exploring the world “with my wonderful wife Andie, and our beautiful daughter Lucia! Work too, is vital, of course. So, after Moscow, he is off for a show to Paris (‘Trains de Vie’ on view until July 26) and then ‘Faith and Prayer’ (July 28 in Tuttlingen, Germany). He is also collaborating with his sister, Bonnie V’Soske, on an extensive biography ‘A Life In Picture’ that will be published fall 2018.

Advertisement

The camera, as he said, truly continues to be his passport.

(Neeta Lal is a Delhi-based journalist.)