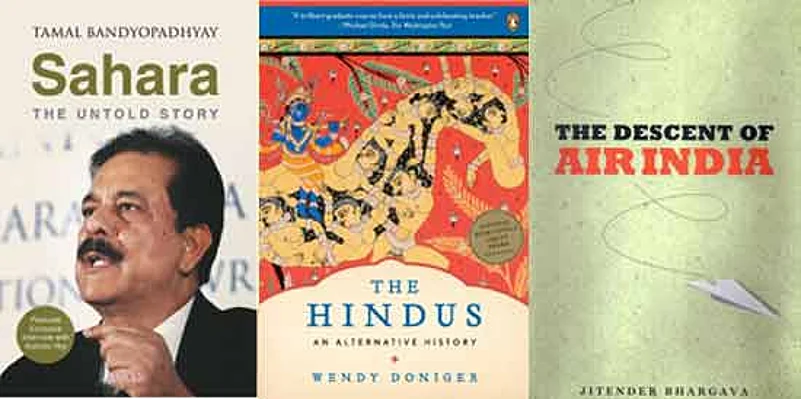

It has not been a good week for free speech in India. First, there was Penguin India’s decision to withdraw Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus from circulation, under legal pressure from fringe right-wing groups—much criticized in the media. Fresh on its heels followed Reporters Without Borders’ annual report, which placed India at a damning 140th place out of 180 countries in terms of press freedoms. Yet even as free speech liberals attempt to regroup, and take stock of a deteriorating situation, there is yet another lawsuit winding its way through the Calcutta High Court, which could have devastating consequences for the independent press in India.

Advertisement

In December, Sahara India initiated a libel lawsuit against Mint Journalist Tamal Bandyopadhyay for his yet to be released book, Sahara: The Untold Story. On December 10, the Calcutta High Court judge stayed the release of the book. Initial indications do not look good for Bandyopadhyay and his publishing house, which has also been made a party to the suit. After reproducing one impugned paragraph, the Judge observed, “Prima facie, the impugned materials do show the plaintiffs in poor light.”

It is interesting that the impugned paragraph in question specifically states that the allegations it makes are unverified: “More such incredible tales abound about Sahara, none that could be substantiated”, is the precise wording of the sentence. How the case for libel can be made out even after that express disclaimer is unclear. But what is truly staggering is the amount Sahara is claiming in damages: Rs. 200 crore! It is an amount that no journalist can afford to pay, and one that would drive most publishing houses out of business. (Although the facts are different, the amount is reminiscent of the Rs 100 crore a Pune Court ordered Times Now to pay in damages, for a fifteen-second clip wrongly showing Justice P.B. Sawant’s photograph in a story about a scam, back in 2011).

Advertisement

It would be bad enough if this was a one-off case. It is particularly alarming, however, because it fits into a larger pattern: the blatant abuse of libel and defamation laws by corporations and individuals in positions of power, to silence critical voices. Hamish McDonald’s The Polyester Prince, chronicling the rise of Dhirubhai Ambani, was not published by HarperCollins in India, after legal pressure. Just last month, Bloomsbury agreed to withdraw Jitender Bhargava’s The Descent of Air India, a book highly critical of then-aviation minister Praful Patel’s role in the downfall of the airline, and apologized to Patel—again, under threat of a defamation suit. And now this.

The trend is obvious, and its implications can hardly be understated. Not only do Indians lose access to important books examining the workings of power and capital in India, the nexus between politics and industry, and other similar issues of vital public interest—but the inevitable effect, as incidents such as these pile up—will be pervasive self-censorship by journalists. Who would want to risk a 200-crore lawsuit, to be contested against a corporation with unlimited resources? And if public debate on these matters is killed, we will be much poorer for it.

Is there a solution? Yes, there is. It lies with the Courts, and it is called the rule in New York Times v. Sullivan.

Advertisement

It is a rule that has been favourably referred to by the Supreme Court in some of its free speech cases, and in the last decade, by the Delhi High Court. Yet if there was ever a time to end the ambiguity, and incorporate it directly into Indian law, the time is now, when press freedoms stand at a critical crossroads.

In many respects, New York Times v. Sullivanpresented a similar fact situation: the use of libel law by a powerful actor, in an attempt to stifle reporting on a critical issue of national importance—the American Civil Rights movement. On March 29, 1960, the New York Times carried an advertisement that described some of the actions of the Montgomery Police force against civil rights protesters. The advertisement carried some factual inaccuracies. For instance, it stated that Martin Luther King had been arrested seven times, whereas he had actually been arrested only four times. It mentioned an incident in which students had been padlocked into a hall to starve them into submission, which actually hadn’t happened. And so on. On the basis of these factual inaccuracies, Sullivan, Montgomery Public Safety Commissioner sued for libel. The Alabama Court awarded him damages of 50,000 dollars. New York Times appealed to the Supreme Court. The stakes could not have been higher, because a victory for Sullivan would have led to a slew of similar lawsuits against the New York Times, that would probably have driven it out of business, and made it extremely difficult for other newspapers to report freely on the widespread suppression of civil rights protesters in the American South. Indeed, the respected American free speech scholar, Anthony Lewis, observed that libel laws were the South’s tool of choice to ensure that public opinion would not be swayed by aggressive investigative reporting of police brutality.

Advertisement

The American Supreme Court, in one of its most famous decisions of all time, held in favour of the New York Times. In words that have echoed in the annals of free speech history, Justice Brennan noted:

We consider this case against the background of a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.

What Justice Brennan and the rest of the Court understood was that in free debate, speakers are bound to make mistakes. If free speech was to mean anything at all, it must be given the “breathing space” that was necessary to survive, and this would necessitate protecting false statements as well as true—especially when issues of vital public importance were at stake.

Advertisement

It was particularly important, because as the Court recognized, the fear of punitive legal punishment was the most effective tool to chill journalistic speech on just such matters of public interest. Again, Justice Brennan put the matter eloquently:

the pall of fear and timidity imposed upon those who would give voice to public criticism is an atmosphere in which the First Amendment freedoms cannot survive… a rule compelling the critic of official conduct to guarantee the truth of all his factual assertions - and to do so on pain of libel judgments virtually unlimited in amount - leads to a comparable "self-censorship." Allowance of the defense of truth, with the burden of proving it on the defendant, does not mean that only false speech will be deterred. Under such a rule, would-be critics of official conduct may be deterred from voicing their criticism, even though it is believed to be true and even though it is in fact true, because of doubt whether it can be proved in court or fear of the expense of having to do so. They tend to make only statements which "steer far wider of the unlawful zone. The rule thus dampens the vigor and limits the variety of public debate.

Advertisement

Consequently, the Court held that to succeed in a libel claim, it must be demonstrated not simply that the newspaper made a false statement, but that it did so either “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”

The New York Times judgment had both short-term and long-term consequences. Freed from the fear of destructive libel litigation, newspapers reported aggressively on the civil rights movement, and played a major part in its eventual victory. And long-term, the press has been insulated from such lawsuits, and has been allowed to go about its business with complete freedom. Consequently, debate on public issues has been robust and uninhibited. Problems abound with the American media, but one thing that is not a problem is chilled journalism under threat of law.

Advertisement

Justice Brennan’s words resonate in India today. Like the America of the 60s, this is a pivotal moment for the future of the free press. There have been a series of reverses of late, but the way out is clear. If we want books about the Ambanis, about our politicians, about Sahara to be published, if we want information and debate about how India’s powerful people act—we can have it. All it needs is one judgment that takes forward the Indian Supreme Court’s qualified approval of New York Times, and expressly makes the knowledge/reckless disregard test part of India’s free speech law.

Advertisement

One cannot be too naïve about this. It is possible that the pendulum will swing the other way, and the threat of an unrestrained and irresponsible media can never be discounted. But there are two things that must be noted: first, prominent political and industrial figures have more than adequate material and social access to media channels to respond to criticism, warranted or unwarranted—a privilege that the ordinary citizen does not have. And secondly, undesirable though the prospect of an unaccountable media is, the prospect of a silenced media is far worse. Sunlight, they say, is the best disinfectant. Admittedly, too much sunlight can distort our vision, but that is better than groping around in complete darkness.

Advertisement

HarperCollins and Bloomsbury’s decisions—and indeed, Penguin India’s decision last week—were motivated, in large part, by the pitfalls of Indian litigation, and the judiciary’s unimpressive record in protecting free speech. With the Sahara case, the judiciary has the chance of a decade to redeem itself, and accord to the press some desperately-needed protection. Let us hope it rises to the occasion.

Gautam Bhatia — @gautambhatia88 on Twitter — is a graduate of the National Law School of India University (2011), and presently an LLM student at the Yale Law School. He blogs about the Indian Constitution at http://indconlawphil. wordpress.com