"The fact is, for the book-collector the true freedom of all books is somewhere on his shelves."

-Walter Benjamin

Academics are plagued with an irreconcilable contradiction throughout their lives: between what they need to write and what they want to write. In this publish or perish market, writing for pleasure seems to be a dying pastime. I have wanted to write about my library for well over a year now; in this time, I have successfully defended my thesis, published an article in a peer-reviewed journal, written some book reviews and political commentaries - in short, significantly expanded my CV.

It was only while moving to Bangalore with my partner and unpacking my things that the inner urge to write this piece became most intolerable. Such is the case with some writings; if cooped up for long, they have a way of forcing themselves out. This piece on 'unpacking my library' is greatly inspired by Benjamin's original, though I will state with some feigned humility that it makes no claim to be of similar literary quality.

Advertisement

Wherever I travel, I pack my books first. I moved to Bangalore from Chennai with two books for academic reading, Don Quixote (which I have failed to finish despite being at it for several months now. I have finished other novellas and short stories in between though), Pablo Neruda's Canto General, and my 'shit book' — TS Eliot's On Poetry and Poets. My 'shit books' are books that I read when, and only when, I take a dump and concomitantly, these are books I read with more discipline than any others. Among the books that I have read in this fashion are Nietzsche's Thus Spake Zarathustra and the 781 paged selected works of Lenin. Along with these, there are three other types of books I try to read in a day with some discipline — a work of poetry, a work of fiction, and a work of serious non-fiction. So, a minimum of four books will always be on my person when I travel. The rest of my books were packed and parceled by my partner with great help from my mother, with much care. Because, often, travel is the enemy of book-covers. And while I do not judge a book by its cover, it is nevertheless important to me that the cover is intact. This might be the conservative in me confessing.

Advertisement

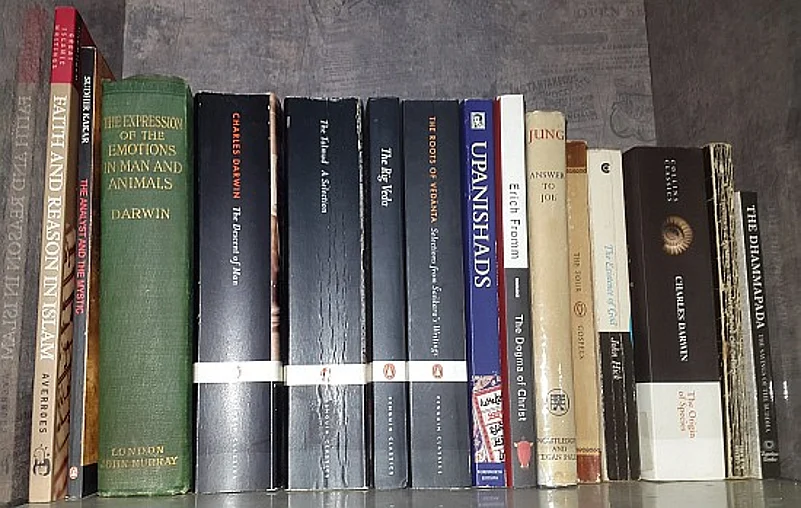

Benjamin states that the book-collector finds himself in "a state of dialectical tension between the poles of disorder and order." Even as I obsess with placing my books in a premeditated order, disorder does inevitably creep in. Arranging books is like running a state; as much as you desire order, there must and there will be space for disorder, not because this disorder is a malignant external entity, but rather internal, even integral, to the system. For instance, I arrange my books in shelves thematically. Within a shelf, they are placed according to size, descending in height from left to right. Yet there are exceptions. For instance, you will find the works of Darwin in the Theology shelf, along with The Talmud, The Four Gospels, and The Rig Veda. And you will find Samuel P Huntington in the Postcolonial studies shelf. The placing of these books is, of course, a deliberate pun on my part. I am just pointing it out here to show that there is ultimately a totalizer who/which fits disorder into order.

Currently I own 980 books (and 26 photocopied books). A small number when compared to Umberto Eco's 30000+ books. However, I can take some pride that George Orwell had less than half this number when he was almost twice my age. While I often contest Orwell’s political insights, I will concede that he did write some good essays like the one on 'Books v. Cigarettes' where he shows that the average Englishman spends more on smoking than on reading. I should confess that I too have spent more on cigarettes than on books. But no complaints here, as the money invested in smoking did not prevent me from investing in books. On the contrary, the pleasure of reading a gripping novel, moving poetry or a profound philosophical treatise is accentuated when accompanied by smoke and the occasional glass of Scotch.

Advertisement

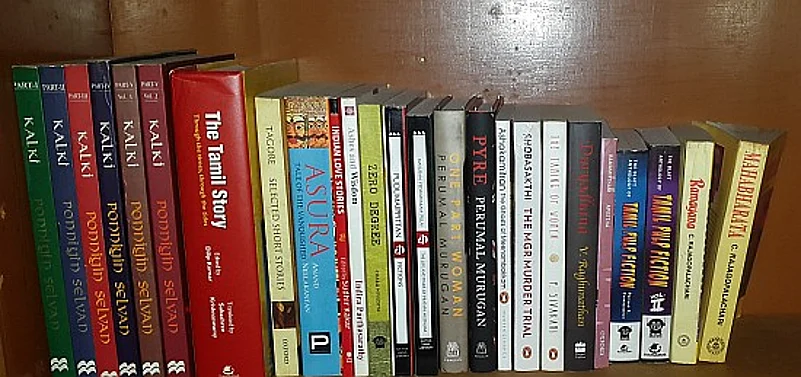

Of my books, 334 are works of fiction — this includes drama, myths, and epics. 65 are what I would classify as English Classics, 48 are French Classics, and 34 works of great Russian literature. I own 30 mythologies and these include Mesopotamian myths, Greek epics and Nordic sagas. Chief among these is The Mahabharatha, of which I have four versions, one classic adaptation and one contemporary 'pop culture' retelling. A prized asset among my Mahabharatha collection is the unabridged 10 volume box set of the epic, which was lovingly gifted to me by my partner.

I have 11 books of Shakespeare, including the Penguin|Viking edition of his complete works. I own 10 books of Marquez and 9 of Llosa, though I prefer the Peruvian to the Colombian. Those who observe my fiction collection will notice that apart from these two giants, there is very little representation of contemporary writing. Well, that is just because I believe life is too short to be reading writers of my own time. And from my time-zone.

Advertisement

My partner, a publisher of critical social and political works in Tamil, is also a bibliophile in her own right and has a splendid collection of Tamil literature. It is the unrepentant Eurocentrist in me that has prevented me from acquiring a Tamil collection of my own; absence of any formal training in the language also contributes to my disinterest. The last time when I was asked to start reading a Tamil novel, my excuse was "I still have not read Victor Hugo. Besides, I spend a lot of my time on Tamil cinema." This would seem ironic for a person who has written quite a bit about Tamil politics and society. But then, I do not need to be a patron of Tamil literature for me to be an analyst of the Tamil polity.

Advertisement

Anyway, my collection of works of Tamil literature is greater than my collection of Indian literature, 13:3 respectively. I am happy to own the first Tamil novel Vedanayagam Pillai's The Life and Times of Pratapa Mudaliar, Pudumaippittan's short stories, Kalki's Ponniyin Selvan, and a brilliant anthology of Tamil short stories spanning over a century. All of these are in English. I do read in Tamil occasionally when required for academic or political reasons, but English is the only language that gives me the best aesthetic experience.

I do get confused at times on the nature of translations — are they contributions to Tamil literature or English? The very idea of having a translation is not just to convey the meaning of the original to someone who is unfamiliar with the language, but also to ensure that the beauty of the original goes across. However, I think that literary beauty is particular to the landscapes and imaginations of the original and those who do not successfully penetrate the universe of the original can never appreciate it fully. Here’s where the genius of a good translator lies – he ‘kills’ the author of the original and creates a new beauty with the original work, such that the reader is left with the impression of having tasted the beauty of the original. So, I would say that the translation is the child of the translator (mother) and the original work (father), which has a life of its own, though it carries influences of its parents. Of course, a great gene combination will give birth to a very beautiful child.

Advertisement

In my poetry shelf, Tamil works dominate — again, as English translations. The Purananuru, Ainkurunuru, Muttollayiram, Ramanujam's translations of agam and puram poems of the Sangam era are testament to the most valued pursuits of ancient Tamils - Love and War. That modern Tamils are failures at both is a different story. Nammalvar and Andal's erotic bhakti poetry, of man and woman's unconditional surrender to their desires for the company of the divine, feature prominently in my poetry collection along with Ovid, Dryden, Wordsworth, Milton, Keats, Yeats, Shelley, Rilke, and other greats.

I finished reading Paradise Lost a few months back. I had purchased the 1968 OUP edition of Milton's poems from a second hand bookshop in Colchester in 2012. To me, part of the aesthetic experience of reading this phenomenal work was the smell from the book's hardbound cover. A work of art indeed! I love aged books with hardbound covers. Though they are quite expensive on the market, I try to spend money on them whenever I visit second hand book stores. Most of my hardbound books were purchased in England. There were two second hand stores in Colchester and a series of them in Leicester Square, London that I used to haunt frequently, specifically to purchase such books. I got quite some good bargains: Samuel Butler's The Way of All Flesh, Eveleigh Nash & Grayson, 1930 for 4£; Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra, JM Dent and Sons, 1935 for 2£; Thucydides' The History of the Peloponnesian War, OUP, 1943 for 2£; Upton Sinclair's A World to Win, T. Werner Laurie, 1947 for 4£; an undated Odhams Press edition of Dicken's David Copperfield for 4£; and HG Well's The Shape of Things to Come, Hutchinson & co, 1933 for 10£. The last one is especially dear to me for being one of the most brilliant futuristic novels ever written and also for its broken spine, that I lovingly mended myself.

Advertisement

But I also spent a small fortune on these types of books. I purchased for exactly 25£ each hardbound copies of Zola's The Mysteries of Marseilles, Hutchinson & co, 1895, his The Beast in Man, Elek Books, 1956, and Charles Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, John Murray, 1904. Then again, the price of the cheapest bottle of Scotch I consumed was around 20-30£!

A generation that has grown reading ebooks on kindle will only note the price of these collections, and not their value. Sadly, they are not even good enough to be cynics. An Oscar Wilde character quips that a cynic knows the price of everything and the value of nothing. This actually is the description of the liberal empiricist, a rabidly multiplying species on earth. The cynic, on the contrary, knows the value of everything, but since the dominant mode of thinking has put a price tag on everything, he loses faith in the concept of value. The cynic is in reality a desperate soul looking for a value to hold on in what he perceives to be a value-less world.

Advertisement

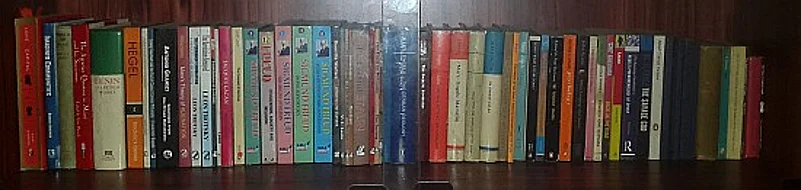

I own 4 bookracks and the position of pride is the topmost shelf of my first bookrack, which hosts my philosophy classics collection. Apart from St. Augustine (who was a North African Berber), the rest are all what the politically correct call "dead white men." The only exception to this rule is Slavoj Zizek, who is alive and kicking, and who, in my opinion, is the only living philosopher worthy of being placed along with Plato, Hegel, Nietzsche, Sartre and Marx. This shelf begins with Zizek's Absolute Recoil, the single work of his that I would prescribe for understanding all of his past and future writings, and ends with Nietzsche's The Gay Science. The shelf below has more philosophy, Beauvoir, Levinas, Laclau, Foucault and some more Sartre – the French existentialist philosopher has the greatest representation in my library. I have 17 titles of Sartre (and 9 books on Sartre). He is followed by Nietzsche and Freud at 14 books each. While I find the pessimistic-optimism of Sartre intriguing and greatly relevant for our times, I believe that the latter two are thinkers who will be relevant even should another species overtake humanity, because few have deconstructed the flaws of humanism to the extent that they have.

Advertisement

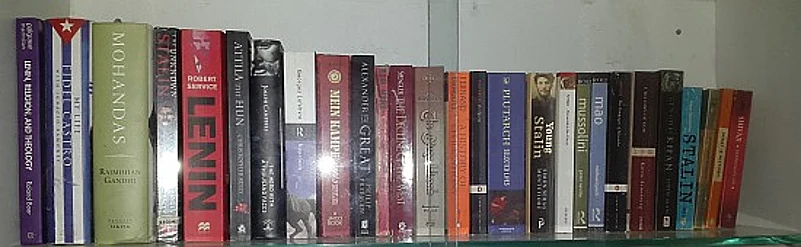

80 of my 604 non-fiction works are on Marxism. I have a reasonably good collection of the writings of the holy trinity of Marxism, Marx-Engels-Lenin, most of which was published by Progress Publishers of the erstwhile USSR. These books have a tragic smell to them, of something good and fresh gone hopelessly stale, like the socialist experiment of Russia. I also have a few works of Stalin, which I place right next to the works of Trotsky just for the laughs. Of the 33 biographies that I possess, 4 are on Stalin. The 'man of steel' from Georgia is the Marxist whose life I find most fascinating in a perverse way; I believe that no contemporary metaphysical study of radical evil can be complete without an attempt at understanding Stalin. Hitler and the Holocaust can be explained rationally — ages and ages of anti-Semitic hatred finding an expression in the modern Nazi state machinery. There can however be no rational explanation for the Holodomor.

Advertisement

The only person whose life fascinates me more is Alexander the Great. From Plutarch and Arrian to more recent commentators, the Macedonian has been seen an exemplary product of human civilization. It is a pity that he finds his place on my shelf along with the likes of Attila the Hun, Genghiz Khan, Hitler and Mao. But then, in that same shelf there is also a massive biography of Gandhi next to The Unknown Stalin. Elsewhere, Martin Luther King sits between Frantz Fanon and Malcolm X.

I am generally picky about my publishers, but I have not been averse to purchasing books published by nondescript ones. For instance, I have 16 works of fiction, including those by Dickens, Woolf, Austen, Wharton and others, by Delhi based Peacock publishers. Each of these books was purchased for about 75 cents and was of reasonable quality given the price. I also bought five major works of Freud published by this obscure group called KRJ for the price of 2 regular cappuccinos.

Advertisement

The major publishing house to found in my collection is Penguin. I especially adore their Great Ideas and Great Loves series, of which I have 23 books and 20 books respectively. Books by Wordsworth Editions and Vintage also figure prominently. But the vast majority of my strictly academic literature is OUP. And thank the lord for Dover publishing the works of Augustine, Hegel and Nietzsche for ridiculously cheap rates!

Even with help from my partner, it took me two full days to unpack and arrange my books. While surveying them in the process of writing this article, I couldn't help but wonder why some books were placed here and not there, why have I purchased the same book twice, why have I not yet opened some books, why have I not yet finished the books I have opened, why are there some books still on the market and not on my shelf... The book collecting passion is not just a "chaos of memories" as Benjamin said; it is also a chaos of the future. Gaps in my bookracks gape at me, demanding to be filled. The last book to be added to my philosophy shelf and thereby filling it was Leszek Kolakowski's Is God Happy? And now, I need to create more space for future philosophy books without disturbing the order that I have established. Or maybe I will introduce a little anarchy...

Advertisement

In my last bookshelf, a bottle of Chivas Regal Extra waits patiently below Simone de Beauvoir's Letters to Sartre. Both are exquisite products that I soon plan to treat myself to.

Dr. Karthick Ram Manoharan is a senior lecturer at the School of Development, Azim Premji University, Bangalore.