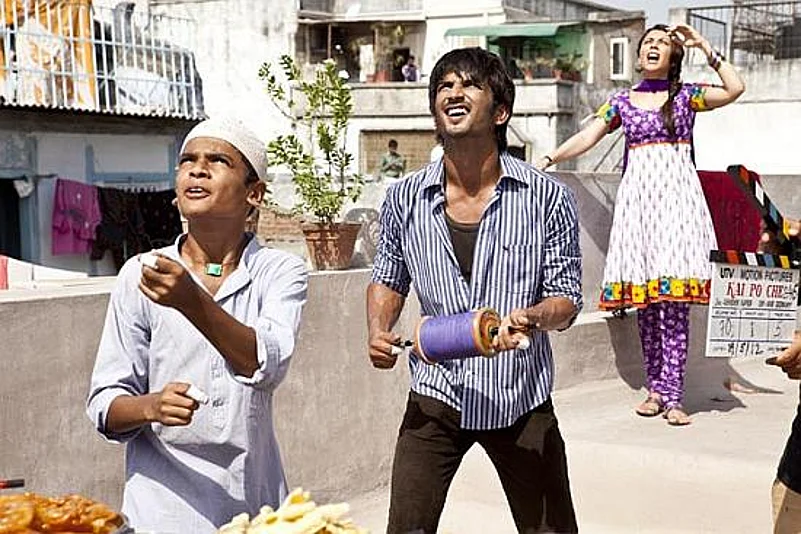

Much has already been written about Kai Po Che, so perhaps I need not even bother giving the usual spoiler-alerts. Most of the readers of this website, even those who have not seen the film, would by now be aware of the basic storyline, thanks to the two pieces that have already appeared here and here. But just for the sake of clarity, let me broadly provide the bare necessary facts once again.

Set in the backdrop of a religiously divided city, the film is about three young Hindu men —Ishaan, Govi and Omi—who try to make their fortune selling sports equipment and offering coaching. The fourth protagonist is a poor, young Muslim boy, Ali Hashmi, who has a ‘God-given’ talent as a cricket batsman. The film has attracted criticism [See here, and here] for a script that ignores many aspects of Chetan Bhagat’s book, The 3 Mistake of My Life, on which it is based. Producers and directors nearly inevitably need to make films that are aimed at box-office success and therefore while it is understandable that many aspects of the book may have been left out, what is troubling is that references to any state-sponsorship of the 2002 Gujarat riots have also been completely written out. The riots in the film are depicted as only the work of a power-hungry local leader. Perhaps this watered down version of the original, it has been suggested, is due to Mr Bhagat’s increasingly close relationship to the Gujarat Chief Minister whom he has praised and defended a number of times.

Advertisement

Whether the film has tried to conceal, even twist, the truth is of course up for debate but, interestingly, the way in which it has chosen to portray the Muslims of Gujarat, and this can be extended to the Muslims of India, actually reflects many of the socio-political ground realities that the community faces. The young Muslim boy's character has about as much depth as a piece of paper. Ali Hashmi is mostly silent in the film, at times angry, always dressed in kurta pyjama and often in a skull-cap. His father similarly has hardly any on-screen time apart from having to regularly defend his secular political credentials. When giving a speech the father calls on a Hindu leader to address the largely Muslim audience. The lack of agency in a way is illustrative of one of the main problems that Muslims face in India today: that they are voiceless. Interestingly, the only Muslim woman shown in the film, apart from Burqa wearing extras, is Ali’s mother. As opposed to the main female character Vidya—sister of Ishaan and love interest of Govi— who is developed as a secondary character, all we see of the Muslim mother is that she is a housewife. Although the usual generalisations about dandia-waving, dhokla-eating Gujaratis are kept to a bare minimum, interestingly, the new stereotype that is depicted is of tight-knit very devout communities that are hungry for success and development.

Advertisement

The main aspect of the film that also points to the lack of agency is the way in which the young and talented Ali Hashmi has to depend on the charity, goodwill and eventual sacrifice of Ishaan, his Hindu coach in order to become part of the Indian national cricket team. This way of imagining and depicting Hindu-Muslim co-existence is of course not new. Most famously, Mahatma Gandhi, in his philosophy of mitrata or friendship, states that ultimately Hindu-Muslim unity would only be possible if the Hindu was willing to unconditionally sacrifice himself for this cause. This is exactly what happens in the film with the likeable character of Ishaan taking the bullet fired by his friend Omi, who is coaxed by his own uncle, the Hindutva leader Bittoo Mama into avenging the death of his parents on the Sabarmati Express by killing Ali Hashmi and his father. The latter, of course, happens to be a political rival of the Hindutva leader.

The film, despite the harrowing experiences of the riot, tries to end on a positive note, something that Mr Bhagat prides himself on. Omi is released from jail, presumably for the murder of Ishaan and joins the third friend Govi who has married Ishaan’s sister and named his son after his deceased friend. Omi, almost cathartically, cries when he sees the young boy’s mother while they all sit down to watch Ali play his first international innings for India. Without giving away the ending, it is interesting to note that the film ends with Ali playing a shot that he was taught by Ishaan instead of hitting the ball in a way that might have occurred naturally to him. As the ball speeds away we are reminded of this with flashbacks of scenes in which Ishaan painstakingly coached Ali.

Advertisement

The success of Ali has a cricketer is ultimately depicted as being something over which he has very little control, other than having the talent which, arguably, is also not really in his control. In many ways the depiction of Ali in this film is symptomatic of the plight of Muslims in India who have not only suffered due to institutional prejudices but also because a coherent and visionary Muslim leadership has not been able to emerge.

The troubling question that the film leaves one with is: Would the success of Hashmi be possible without the benevolence of Ishan? Should the success of a person, let alone a Muslim, be contingent on the benevolence of any particular community? Of course Gandhi’s idea that we should selflessly help others is an important concept but not if that help is based on identifying others by their ethnic or religious background. Clearly, there's a lesson here for our politicians who must understand this basic premise and stop the cynical use of religion as a convenient electoral tool and look at individuals as citizens.

Advertisement

Other controversies aside, what cannot be denied is that the makers of Kai Po Che have made a film that has, at the very least, tried to tackle the thorny issue of Gujarat and introduce it into mainstream cinema. This in itself is commendable. However, the film industry also bears the responsibility of holding itself to higher standards given that the medium has a far-reaching impact in moulding public opinion and has the power of breaking or entrenching prevalent stereotypes and ideas.

Ali Khan Mahmudabad is a PhD student in History at the University of Cambridge who writes a fortnightly column for the Urdu Daily Inqilab.