When I was growing up in the un-liberal India of the 1970s-80s, starting with Hollywood films such as Ben-Hur and Gone with the Wind and going onto On Golden Pond and Deer Hunter combined with the often bleak and funny literature by J.D. Salinger or Joseph Heller created an exotic "abroad" or "Other" in my mind. For a young Indian like me, westernised angst was more compelling than humdrum Indian reality. This other preferable world I imagined also had tremendous dissonance with shrill-sounding Hindi melodramas while Indian English literature was still in its incipient stages.

A still from Gone With The Wind

Advertisement

Then things changed with the aesthetically pleasing artistic films by Shyam Benegal, Aparna Sen and Govind Nihalani in the 1980s, which facilitated self-reflection in the Indian middle class. On his part, Salman Rushdie wrote shockingly innovative Indian-style prose and Indians like me suddenly felt an active engagement with our own decolonisation by being able to see and hear contemporary Indian modernity described in new terms. But, I also surreptitiously watched other affective Hindi film melodramas on TV, though I was wholly uncomfortable with the climaxes and emotional outbreaks that would inspire embarrassing or "gross" and tearful responses in me. And I know I wasn't the only one in a generation a little uncomfortable with the colonial legacy of the English language culture but also uncomfortable with local popular culture so that Benegal's and Nihalani's Middle Cinema and the Indian English books were long-awaited by people like us.

Advertisement

Twenty years later, now a Canadian, I'm watching Indo-Canadians responding to Bollywood films entirely without the squeamishness even though they constitute an overseas audience; they are completely comfortable with their parallel subscriptions to Bollywood and Hollywood unlike I was, which really demonstrates a shift in both representations of Indian identity and also in their reception. It could be because, they have access to first-release Bollywood films that also converse directly with the overseas diasporas by having incorporated diasporic stories. Bollywood's revenues for 2007 amounted to $200 million, which though just 20% of the total represents a sizeable and growing chunk of Bollywood's profits while films themselves are easily accessible and apart from the trendiest Bollywood releases, many young diasporic Indians have gone on to familiarize themselves with the older Umrao Jaans, Pyaasas and Mother Indias cheaply bought at any Indian video store.

Nargis in Mother India

Significantly, though, it is the new films that first attracted youngsters as they represent a more cosmopolitan India and Indianness they can comfortably identify with. At the same time, the globally ensconced diaspora, including established Indian authors like Jhumpa Lahiri, Rohinton Mistry or Shashi Tharoor have had a big impact on representations of global Indianness and given Indians and South Asians, generally speaking, a greater range of styles, personas, stories and situations to "imagine" themselves from if we acknowledge Benedict Anderson's theory of imagined nations being created out of media forms.

Advertisement

Diasporic films such as Mira Nair's The Namesake and Deepa Mehta's Heaven on Earth (2008), or even the less known Sweet Amerika by Vancouver-based Paul Dhillon demonstrate how influential diasporic film-makers have been in terms of a modern Indian identity that is hybrid, reactionary or completely uncertain.

Compared to litterateurs and diasporic film-makers, though, Bollywood has emerged as the most successful manufacturer of Indian identity and the ubiquitous global Indian of these films -- trendy, cosmopolitan and affluent -- has circulated widely enough to become representative of modern Indianness in the public imagination.

In this regard, the diaspora's role with respect to Bollywood is much more than a nostalgic overseas audience. As audiences go, it is arguably very influential in the manufacturing of a new global Indian identity because the diasporas present the larger space of Indianness abroad. While Bollywood has created an imagined diasporic community, it has also found a means through the diaspora to assert modern Indianness globally.

Advertisement

With the diaspora having become more visible than ever, India has acknowledged its need of the ideas of the immigrants (apart from their money) and as incongruous as it seems, globalization has actually re-territorialized the diaspora through popular films. This is quite apparent in the many appeals to the diaspora including by erstwhile Indian governments who now piggy-back on Bollywood to sell India abroad and are happily promoting mainstream Hindi cinema after decades of having badmouthed it.

Preity Zinta in Heaven on Earth

What's more is the fact that boundaries between Bollywood and diasporic films themselves have blurred since Deepa Mehta, Gurinder Chaddha and Mira Nair began using Bollywood stars as protagonists. Deepa Mehta's recently released Canada-based story Heaven on Earth, is a cinematographically innovative story about Chand, a Punjabi immigrant played by popular star Preity Zinta, who faces massive disappointment and sadly escapes into magic realism to cope with her tortured new life in Brampton, Ontario. The mainstream value of this film is quite obvious in terms of Deepa Mehta's high profile status within Canada as an intercultural film-maker.

Advertisement

With the profusion of images and stories, the visibility of Indian culture and Indians abroad has often inspired talk about India's soft power surge. I'd say, however, it is equally the fact of Indian diasporas having come of age outside India. By this, I mean overseas diasporas have created and claimed a largely self-propelled space for South Asian/Indian culture. And diasporic identities are essentially different from identities imagined and produced in India as the process of them 'becoming' a diaspora changed their identities. How this has come to a head with modern Indian globalization and the need for Bollywood producers to compete with foreign media products, is a matter of coincidence as well as the efforts of diasporic Indian scholars and writers that have come to fruition.

Advertisement

Bend It Like Beckham

Around the turn of the millennium, a spate of intersecting events put India abroad in the spotlight: The entries of Lagaan (2001) and Devdas(2003) for the Oscar film competition along with Gurinder Chaddha's Bend it Like Beckham (2003), Andrew Lloyd Webber's Bombay Dreams(2002) and Baz Lurhman's Bollywood-aesthetic inspired Moulin Rouge, suddenly amounted to a critical mass of Indianness on display. Together with India-centered exhibitions, henna tattoos (as they're called in North America), ethnic Indian fashions and Indian music became part of a mainstream interest outside of India. The acceptance helped second generation Indians in the UK, USA and Canada to wholeheartedly engage with Bollywood music and choreography publically. All of which have helped create the 'cool' Indian image that has spread rapidly through the diasporic capillaries of food, fashion and films that immigrant communities typically express themselves through.

Advertisement

From having survived, South Asian diasporas have shown how they thrive in 'Third Spaces' outside the subcontinent created by immigrants in western metropolises who are able to mark a space out for themselves somewhere between dominant and peripheral societies. Their own status as postcolonial subjects has made immigration to western societies, in particular, a space of immense tension as they have often had to deal with the process of their own decolonization. It has led to a process of self-reflection and a plethora of cultural products connected to a modern Indian identity.

Advertisement

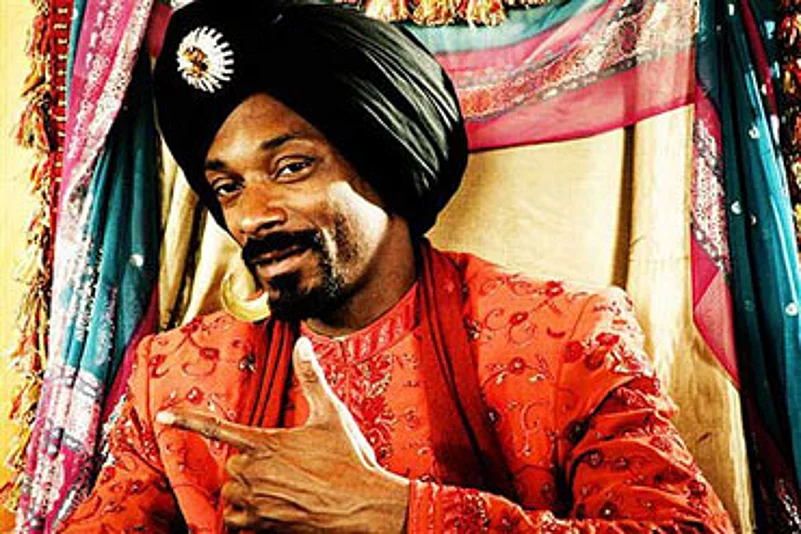

Snoop Dogg in Singh is Kinng

The 'coming of age' argument I'm making, has also arguably had a profound influence on contemporary Bollywood as bhangra-rappers from the UK and Canada have sent fusion sounds back to Bollywood. Canadian bhangra and hip-hop, including Jazzy B's music has been channelled to Bollywood while Western artists show a great fascination with Bollywood's different signifiers and images. This is how hip-hop artist, Snoop Dogg, has entered Bollywood in the film Singh is Kinng (2008), with rhythmic hip-hop that is entirely compatible with Bollywood choreography. Meanwhile, Bollywood film producers have consciously been spending ever larger sums on film music as they see in affective Bollywood songs the best way to market so-called Indian values, romance, ethnicity and fashions.

Advertisement

As stories wear thinner than ever, future changes will include a greater number of USA, UK or Canada-based Bollywood scripts. For instance, British-Columbia-born Arjun Sablok working with film producer Yash Chopra, contacted Vancouver film students in March 2008 strongly encouraging them to submit their own film scripts as there was a need for fresh stories that were not being produced within India.

While films produced under the Yash Chopra banner rarely describe immigrant life accurately or meaningfully, they have been extremely popular with Indian diasporic audiences as the Hindi language culture, fashion and commercialised ritual they proffer is greedily consumed by the second generation diaspora who also account for a large number of overseas film viewers. For them Bollywood represents India.

Advertisement

Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge

In fact it was the youngest audiences who first endorsed the glamorised misé-en-scéne of the contemporary films first seen in Yash Chopra's Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (1995). In the film, Shahrukh Khan was affluent, trendy and lovable and first represented the new Indian identity as being transnational.

After 13 years, the startling tendency to favour affluence, a self-congratulatory stance about being global and unabashedly consumerist remains strong in Bollywood films. In addition, the India that has been manufactured for these narratives is upscale, fantastically beautiful, ethnic and modern simultaneously. The wish-fulfilling narratives portray a transnational Indian bourgeoisie who are confident and proudly Indian, whether they live in Toronto, New York or Mumbai. There has rarely been any questioning either of the dominance of the images in these films or of the hegemony of Bollywood itself, which now admirably rivals Hollywood but has also picked up its worst habits.

Advertisement

Quibbling aside, though, there is a local Bollywood in almost every western city and at last South Asians can participate in traditions that hark back to the subcontinent whether it is the style of eastern melodrama or the musically-imbued narratives. For instance, a Canadian Bollywood exists in Bollywood-style weddings, parties, choreography classes and fashions in Toronto and Vancouver. The highly acclaimed choreographer Shiamak Dawar has endorsed Bollywood classes in Vancouver while 10,000 fans craned their necks to watch the Unforgettable 2008 Tour led by Amitabh Bachchan and more than a dozen other Bollywood stars in Toronto this summer. The overseas visits by superstars is linked to their acknowledgement of overseas fans and ultimately to how much this affects their own pay checks today.

Advertisement

Salam Namaste

What's interesting is the fact that overseas diasporic fans also watch Britney Spears concerts, soccer or ice hockey matches with the same fervour and straddle two distinct cultures in this sense. In terms of contemporary Indian identity, this dualism is somewhat explained by Partha Chatterjee's notion of inner and outer domains or separate private and public spaces we inhabit. Chatterjee used the notion to explain how nationalism was born in pre-independence Indians who discovered a distinct "inner" world of language and religion that constituted a domain of sovereignty but didn't relate to their "outer" worlds dominated by British colonialists.

Advertisement

The notion that Indians divided their worlds into an inner and outer is problematic given India's long traditions in multiculturalism and an inflow of global influences from the earliest days. That's why Bollywood's artificial inner and outer divisions are unhealthy. Films in which protagonists are situated in western metropolises are dealt with by refusing to let east and west converse at all. References to a Caucasian 'other' are often dismissive like Salam Namaste (2005) in which white girls are sluttish and/or stupid. Unfortunately, as problematic as the concept is, it resonates within large sections of the Indian diaspora who have encountered the inside/outside divide in their lives overseas. For post-1965 émigrés in North America, who form the biggest number of immigrants, decolonization is an uncomfortable truth that we must face. One of the effects of a colonial past is that it still profoundly affects how we define ourselves, which is often in opposition to a western world and so-called western values rather than acknowledging our own hybridity or multiculturalism. Even our own so-called eastern family values are an amalgamation of Hindu, Islamic and Victorian mores if we cared to look closely enough at social constructions particularly of Indian women.

Advertisement

Rang De Basanti

There is occasionally some rethinking of the Indian past in films such as Rang de Basanti (2006) where characters do not accept barriers between their private and public lives and also actively re-engage with past conversations in Indian history. More often than not, though, contemporary films focus on the private or romantic domain and have reinforced this tendency by moving most of narrative inside the homes of the diaspora and fuelled the myths of the Indian family values and morality; this effectively distances the lives of protagonists from socio-political realities. By contrast, diasporic film makers have explored numerous instances of hybridity and crossing over that contrast strongly with Bollywood's crossover films in which the only crossing over has been a hybridization of language and dress.

Advertisement

Having said that, however, Bollywood's significant impact in the manufacturing of a contemporary Indian identity is undeniable. In 2002, US-based Parag Khanna described "Bollystan" -- as a virtual Indian universe created from the import-export marketplace of writers such as Salman Rushdie or Jhumpa Lahiri, a spiritual essence and cinematographic border-crossing. Bollywood's significance in this virtual universe is undeniable while Khanna's pithily described Bollystan is a strong reality for the Indian diaspora.

Still, Bollywood`s wholesale projection of modern technology in contemporary films shows a painful shadowing of western capitalism's mistaken belief in technology as the road to the future. Evidence of Western capitalism's sponsorship of individualism, alienation and overall imbalance, is entirely irrelevant to Bollywood`s globalizing producers who project transnational Indians as technically savvy and ideologically geared towards massive consumerism. Even Indian ethnicity inserted via rituals and songs have become consumer-oriented offerings much like quickie Hindu mantras available globally.

Advertisement

The Namesake

To be fair, India should 'feel good' and Indians should buy plenty after having coming through a painful colonial past and relatively less privileged status. But, popular culture that only engages with wish fulfilment and completely denies less than 'feel good' realities such as hybrid Indian cultures, less glamorous Indians or an underclass than affords most Indians their privileges, shows terrible weaknesses. Besides, these films also deny that Indians overseas belong, in part, to different worlds and as such cannot be re-territorialized or led back to India unless it is through opportunities that will gain them benefits or privileges.

Advertisement

There is a glimmer of hope in films by Nagesh Kukunoor or Rajat Kapoor. In Kukunoor's Dor a young secluded Rajasthani widow discovers female empowerment through a female visitor from Kashmir. She doesn't have to be dressed in blue jeans and a cropped top to do this although she does have access to a mobile phone and modern communications that have taken her husband away to the middle east as a labourer. Rather than these strong narratives, we are given wealthy, 'Hinglish'-speaking females with a frustrating traditional-yet-modern mould. Though many films have broken the mould, for every Dor there are still 20 Salam Namastes made in which complex diasporic identities are simplified by a globalizing film industry fixated by outward appearances and unsure of how far to go in making changes in a society where the global and local have produced as much tension as they have market opportunity. With Indian identity being created far beyond Indian borders and the diaspora having become arbiters in the project, Bollywood and India can expect much more of both.

Advertisement

Post script: In fact, the runaway success of Danny Boyle's Slumdog Millionaire and the strong possibility of its winning something soon, puts the Bollywood Indian into focus even more sharply as someone who has been noticed and spotted by Hollywood while the appropriation of Bollywood stars and melodrama for this movie reveals on just how many fronts Indian identity will be seen.