Way back in the 1990s, economist Dipak Banerjee had introduced a new word to a bunch of young students of the Centre For Studies in Social Sciences in Calcutta: “polyphony,” or music where many notes and melodies play out simultaneously. It was his way of teaching. He would draw on musical analogies to break down economic processes. With his son, Abhijit Banerjee, winning the world’s most glorious award, the Nobel Prize, the memory of his classes comes alive. For, ironically, it is polyphonic economics that has got a shot in the arm with the Nobel announcement.

Understand all the Voices

Advertisement

“Every economic process is like polyphonic music. A multi-voiced dialogue between different positions, the rich and the poor, the policymakers, public opinion, the press and so on,” professor Dipak Banerjee used to say. He was in his sunset days, after a distinguished track record at the London School of Economics and a lifetime of teaching at Presidency College.

We did not understand much of what he taught. We often could not decipher his chaste English accent. We had no idea that he was a music connoisseur par excellence. We found it easier to relate to his wife Nirmala Banerjee’s lectures on feminist economics. But we all knew that their son was the super-brilliant (and the handsome) Abhijit Banerjee—or Jhima, as they fondly called him. Abhijit was a bit of a youth icon to Calcutta college-goers of the time, inspiring many to take up economics or to follow the Harvard-MIT route, instead of Oxbridge, to higher studies.

Advertisement

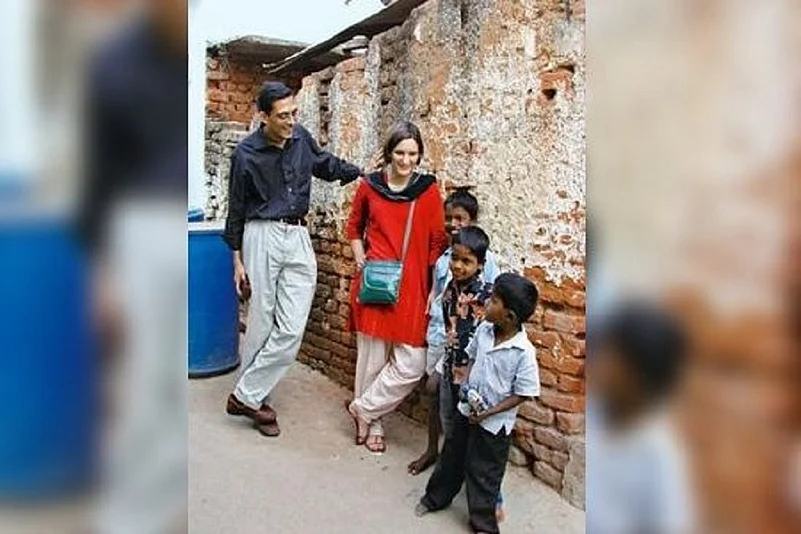

Banerjee, like his late father, practices polyphonic economics of poverty, one that listens not just to the masters of international finance but to the ideas, attitudes, beliefs, perceptions, values and lived experiences of the poor. “Every time we make policies, we forget that the poor have ambitions and aspirations,” he says. “Talk to them, they have a sense of what they want, the life they want.”

The Saptaparni Moment

Nirmaladi, as we used to call her, was a personification of beauty and grace, who spoke Bangla fluently albeit with a bit of an accent—her Maharashtrian heritage. She was the leading light of Sachetana, a feminist outfit based out of her home at 31, Mahanirvan Road, and mentored many a young women of our generation. Pragmatic and no-nonsense, she says that she has never “dreamt” for her children. Both her sons were good students but not the top students in school. He was interested in too many things: music, sports, and cooking. And, she insists that Abhijit is not just the pride of Bengalis, he is half-Marathi too.

But right now, he is the pride of Saptaparni, the cluster of seven buildings on Ballygunge Circular Road, where the Banerjees have moved on to. “Very proud moment for us,” women are buzzing on the Saptaparni WhatsApp group. “An incredibly proud moment for Saptaparni as well as India. What glad tidings,” they are writing. Many are shocked to find a sea of journalists swarming the sprawling complex, TV cameras going up and down the lifts and the crowd in front of her eighth-floor flat, 86F.

At 4:45 pm a celebration has been scheduled at one of the community halls, the small deck, with the Chairman of the cooperative, Anupam Dasgupta requesting all members to attend—to congratulate Nirmala Banerjee. A member, immobile with broken bones and casts, is cursing her luck: “Oh, what a miss! Curse my fractured ankle! Is there any heavyweight champion at Saptaparni who can carry me to the venue?” Someone else, on a trip to the US now, is enjoining everyone to inform her mother: “What a lovely moment. Please ask my mother to go too. Aunty is fond of my mum. I don’t think she’s aware of this deck programme.” Someone else has posted on social media: Dear World, Bengalis are much more than “ami tumake balobase.”

Advertisement

With Durga Puja just over, the festive spirit promises to prevail. As a resident writes in: “October has not yet ended and…

—Kolkata becomes the only Indian city to win the Green Mobility Award

—Dada becomes the BCCI President

—Dr Abhijit Banerjee becomes another Bengali Nobel Laureate.”

Malnutrition Moment

It’s a big moment, too, for Outlook Poshan, the group that raised a singular question on the 73rd year of the nation’s Independence: “What about azaadi from hunger?” With the 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics going to a trio of economists, Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer, who have spent their life analysing global poverty, hunger and malnutrition, the problem of a billion hungry people—one-third being Indians—the power of hope is real. As Basanta Kumar Kar, the Country Director of Project Concern International-India says, “I am happy that economists who have worked on nutrition have received the Nobel Prize in Economics.” Banerjee has conducted extensive research on anaemia, he explains. “It indicates the right direction in global thought process: that good nutrition is above all good life.”