The hall could seat 900 people, but there were many others standing in a queue, waiting anxiously to enter the auditorium to watch Amol Palekar in Kusur, the play that marks his return to the stage after 25 years.

The organisers of the Tata Steel Literary Meet, who had invited Palekar to perform in Bhuwaneswar, were very anxious, but they need not have worried. The hall filled quickly and quietly, and 150 people who could not find seats left without any fuss.

Nothing critiques a show as frankly as the behaviour of its audience. And the audience held its collective breath and watched enrapt as the play unfolded. A deft mix of technology that included lights to indicate which of the four phones in the police control room was ringing, and voices at the unseen end of the line and superb, controlled acting unravelled through 90 minutes of play.

Advertisement

Not missing a cue or a beat, Palekar stumbled and shuffled across the stage, picking up phones, conducting conversations and finally embroiling himself in the story of a woman being held captive in a car by her husband as he made the character of a suspended policeman come to life. His body language was so much in sync with the character that one had to look hard to discern in the slightly bent, fragile frame of the once ebullient actor of Gol Maal, Chit Chor and Rajnigandha.

Keeping up the tension created visually was the mix of unseen voices that demanded help for calamities ranging from fire in a building to the inability to find a taxi to what could well develop into a kidnapping or murder case. The voice actors did their job so well that one could almost imagine their distress or ire.

Advertisement

Adapted by Sandhya Gokhale Palekar from the Danish Den Skylidge by Gustav Moller and Emil N Anderson, the play had local flavour to resonate with the audience, especially in climax which exposes how the best of intentions can be sabotaged by our tendency to hold preconceived notions about people and things.

At the question and answer session that followed the thunderous applause, Palekar, now looking more like the person we know, spoke about how he had to unlearn a lot that the years in cinemas had layered on his acting, to take to the stage again. “Every artist does Riaz,” he said, “but actors just take their art for granted. I had to work hard to negate the years of neglecting to hone my craft.”

The spell he cast on stage proved his efforts had paid him back handsomely indeed.

***

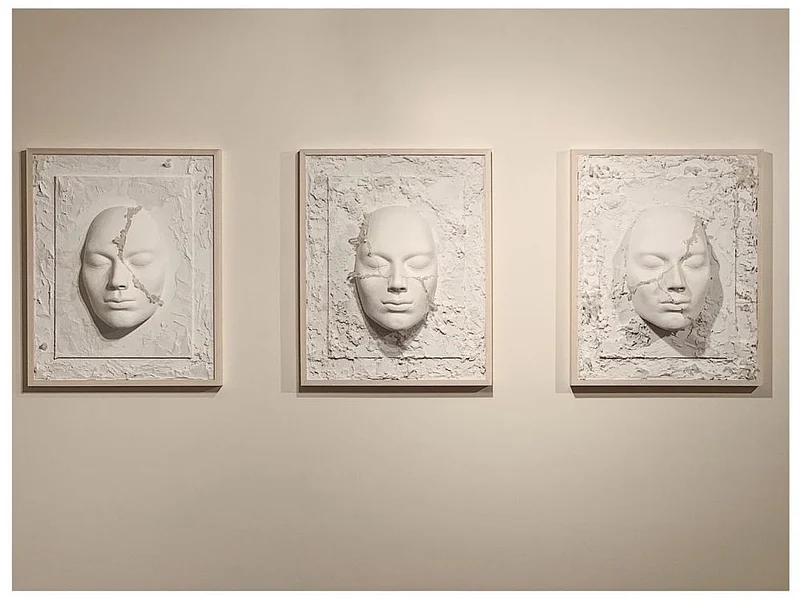

An offbeat exhibition titled ‘Dear Women’ in Mumbai called out to women to ‘remember their innate powers.’ Hoping to raise awareness about the need for men and women to live as equals, Thai-Indian artist, Amonwan Mirpuri, has created four walls that speak of the stages that women, who are abused, go through before emerging from the violence to find themselves again.

Plaster of Paris casts of a woman’s face on a white background form the base of her story. Using the walls of the space, Mirpuri begins with the Wall of Disruption/Destruction that indicates the trauma experienced from the abuse and self-blame, the confusion and the feeling of isolation that follows. Marring the background with scratches and charcoal lines, Mirpuri shows the anger boiling within, while chipped surfaces on the face are scars of the physical abuse. The choice of plaster represents the strength in women but at the same time so delicate and we are to be handled with care.

Advertisement

Moving to the second wall, of Acceptance, Mirpuri now gives the face a calmer expression to denote that the victim has accepted that there is violence and she needs to deal with it. To denote the transition to a desire to move on and away from the source of abuse, the artist let the plaster interact with the face. The pain is thus a stepping stone to growth.

In the Wall of Healing, quartz crystals are seen sprouting from cracks on the sculpted faces. The artist uses this to signify the expression of the will to heal oneself from within. She admits the influence of kintsugi – the Japanese art of precious scars where broken pottery is mended back with gold implying that there is beauty in imperfection and that broken objects can be fixed in a way that make them more beautiful than their earlier state of “perfection”.

Advertisement

The last stage of healing, denoted by the Wall of Life, uses dried flowers behind a translucent fibre glass face to denote the creative energy of women which allows perfect healing much as Nature heals herself after a calamity. ‘To be kind and gentle to oneself because we’re all going through the same journey in different forms. To be forgiving and patient just like Mother Earth has been with us because the process of healing cannot be rushed,’ is what the last trio of sculptures signifies.

Situated as it is close to the High Court and in a busy bylane in South Mumbai, the exhibition has seen many curious lawyers as well as students and office women walking in. Some have been moved enough to leave little notes in the blank cards the studio hands out to all visitors. The fact that the artist has explained each of her walls with framed write ups and poems converts a static show into a powerful message. Sure to resonate and inspire any woman who has been a victim of abuse, physical or psychological. And as statistics show, of that there are plenty, in every country across the globe.

Advertisement

(The writer was the Editor of Femina for over a decade)