The year 2016, and the period counting up to the present, came as an epic moment in the recent political history of Kashmir. It had its roots in the mass street protests of 2008 in which over 60 people killed. The roots were watered—first a bit in 2009, and then in a major way in the bloody summer of 2010, which recorded over 120 deaths at the hands of Indian security forces.

But what transpired in 2016, the way the scales tipped, will take a more thorough understanding of the contextual causes, the deep symbolic elements, the way events on the ground changed colour, and the potential implications of such a mass-based resistance movement.

Advertisement

To begin with, by the closing stages of 1990s, a militant's funeral had ceased to be an ‘event’—it had petered out and was no longer the brawny mass affair it once was. The ceaseless conflict of that decade, in which thousands of people had been killed, both armed and unarmed, had left chaos, fear, confusion and fatigue in its wake. But the new wave of militancy reclaimed that old edge in 2015, with a revival in popular participation.

It started with the killing in November ’15 of Abdul Rahman alias Abu Qasim, a Lashkar commander who carried a cash reward of Rs 20 lakh on his head. The signs were unmistakable at his funeral: pro-azadi Kashmiris were united in extending solidarity to, and expressing a kinship of cause with, the figure of the militant. People actually fought while claiming his dead body.

Advertisement

This was, of course, followed by the tumultuous events after Burhan Wani’s killing just over a year ago. Thousands showed up at his funeral—passions ran high in what was, in the participants’ eyes, clearly a martyr’s farewell. Even the state had not expected it; Mehbooba Mufti herself talked about the desirability of “giving him a chance had they known it was him”.

If one is to answer the "why" of this phase, one has to know its "how" first. The mass protests that became a definitive gesture for the present Kashmiri generation was met with brute force right from 2008. A generation of Kashmiri youth, exposed over the years to this second phase of State oppression, gradually shed their psychological distance from the gun, that old and largely discarded symbol of resistance. As a symbol, it seemed to empower them in this war of asymmetric power.

From a different perspective, the suppression of the 2010 uprising—an agitation within the democratic space, after all—also extinguished the possibilities of a politics of hope. The State was, unwittingly or otherwise, party to this: it propagated a kind of terminal narrative about the lack of any “tangible” results from such an uprising.

In that atmosphere of despair, the idea of human rights being trampled upon—protest being met with bullets—too became a secondary cause, one that stimulated the new turn to the gun. This doesn't imply human rights violations are to blame for armed insurgency but suggests they accelerate the journey towards it.

Advertisement

And then, unlike the ’90s, this was all happening during the dawn of social media. In an advanced, globalised world, information flows as rapidly as blood in the human body, and in the context of Kashmir tended to diminish the gap between militants and the public. This new bond fascinated the youth; ‘owning’ the militancy publicly became a way of articulating people’s power. It made the movement for azadi more prolific and dynamic, especially at a time of disillusionment with “peaceful methods” of dissent.

The coming to power of PDP, with the avowedly ‘Hindu nationalist’ BJP, provided more reason to not give in to diplomatic methods of conflict resolution. In the PDP, the Indian State had cultivated a “soft separatist” party that scores points on either side, depending on whether it is in power or opposition. In the BJP, Kashmiris saw a truer manifestation of how the Indian State had always behaved in the Valley: an aggressively homogenising force forging its idea of Akhand Bharat with iron force.

Advertisement

It’s in the context of the popular distaste for this coalition—a strictly unconscionable one, as far as the common Kashmiri was concerned—that the synchronisation of the militant-public relationship became vivid. Such as when, within minutes of the news of Burhan Wani's death, loudspeakers blared with pro-azadi slogans, and people marched to Tral, and stoned police stations and army camps.

It was the dawn of a war between people and the Indian State that would last a good six months, and whose repercussions are still being felt. For the next six months, the State only existed in its repressive apparatus—speaking only via the medium of pellets, bullets, teargas shells, curfews, Section 144, PAVA shells, PSA, nocturnal raids, illegal detentions.

Advertisement

Emerging against it was a collective discourse that carried for its young adherents the promise of a new Kashmir. Boys like Burhan were a home-grown marker of this new political culture, who gained popularity by connecting the present to a long history of armed resistance. His killing unleashed a sort of madness, of loss, of hatred. The more literate saw it as a frenzy of decolonisation.

The events of the year become an important tool also to evaluate India’s response, and the forms of abstract and real violence embedded therein. People of all age groups suffered—from children to octogenarians. Pellets found their target without discriminating, feeding the fires even more.

Advertisement

Mosques became the epicenter for political activities—they were more political than religious. Social and political mobilisation took place across the Valley, especially in the countryside. It was all decentralised: there was effectively minimal communication with the top leadership, which remained caged for the entire period. Local leaderships sprung up and took charge of events on a daily basis. To sustain the mass uprising, local Baitul Maals (treasuries) were set up, again from the mosques. The sustainability of it all also became a subject of analysis.

The immediate trigger for such a massive uprising could have been a land grab like that of 2008, or a fake encounter like that of Machil in 2010. But it was neither of the two. It was particularly striking that a militant’s killing would incite an uprising that had no precedents in entire Kashmiri history. It was a clear sign: for people, the means of political socialisation now necessarily included the militants. Counter-violence was seen as a necessary part of protests, given the sheer scale of military presence in the Valley.

Advertisement

Six months or so down, when a sense of “normalcy” was restored after many more killings, arrests, detentions, night raids and crackdowns, the State began formulating harsher approaches to deal with a dissentient population. The policies of the government reflected the clear-cut agenda of the inherent ideologies of its constituents.

The Indian State was realising the dream of its genesis—that of a Hindu confessional state, to quote Perry Anderson. For Kashmir, it meant fake diplomatic talks and disguised resolution offers would no longer be a part of the official Indian policy on Kashmir, if there exists one. Instead, ever so often, ‘tough’ words would make it to the headlines. (As in Gen Bipin Rawat’s statement honouring Major Tarun Gogoi for using a Kashmiri as a human shield.)

Advertisement

The denial of legitimate political rights was all along ‘normalised’ by the idea of that denial itself being just—a style of rationalising held aloft by false narrativisation in mainstream Indian media. The international media seldom turned their cameras towards Kashmir, which cast the Valley into deeper oblivion and seclusion on the global political map. The defactualisation of Kashmir was helped along by the deliberate ignorance of Indian people, who in a deeper sense are complicit and equally culpable for what the abstract ‘State’ does in their name. The role of solidarity-givers has been as good as nothing.

But 2016 changed that too. The appearance of Burhan Wani in leading newspapers of the world, borne on the shoulders of grieving, angry, bleeding masses of protesters, shattered the old opacity. A ham-handed internet ban had an effect opposite to intention: curiosity was piqued, and information travelled even faster in response. In a world without the internet and other things one now takes for granted, the old ways stepped into the breach. People went back to traditional modes of communication and a barter system of labour (in absence of outside labour).

Advertisement

By the end of 2016, around hundred new faces had signed on for the militancy, even as the State upped its offensive measures. Its forces had to operate on two dimensions—fight armed militants cordoned off in some house; and tackle youth, armed with stones, converging on the site. Its response was identical in both cases. Along with militants, every encounter would entail the death of protesters by what the army called “stray bullets”. Between people zeroing in on encounter sites to help militants escape and what the forces passed off as “collateral damage”, meanings blurred and categories bled into each other.

Advertisement

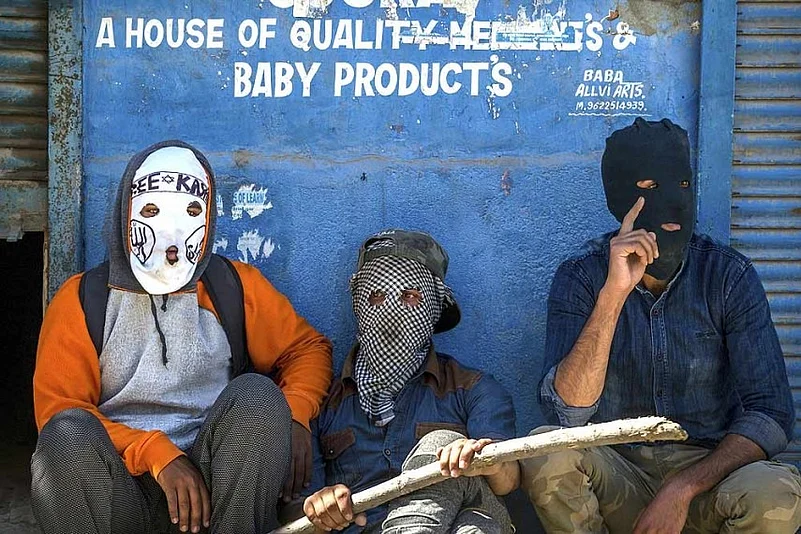

As every single inhabitant of the Valley came to be seen as enemy of the State, it actually bolstered the political logic of the agitation. In the long-term view, a welcome change for the azadi-parast. The whole thing had a self-fulfilling force. The youth marching to encounter sites were not only adding a layer of protection around the militants. They were applying a new, insurgent coating on themselves. Identifying with the figure of the militant, drawing inspiration from it, they were actualising the last thing the State would have wanted: unanimity between militants and the public.

The State too has been changing. Back in the day, when the Al-Fatah module was busted, the government accommodated almost all of them in different departments. In the ’90s, there were perks on offer if a militant surrendered or worked for the State. In the present wave of militancy, the primary objective is only to kill them. The new militants too are from a broken generation that seems beyond the old deal-making—they are those who have seen worldliness and deserted it.

Advertisement

Violence and counter-violence…people tend to locate themselves at a morally justifiable end of that binary. Indian public opinion has one view—but it comes from the other side of the iron curtain, or rather, a curtain of lead. In Kashmir, the brutalisation is so complete that counter-violence is seen as valid—a mode of resistance, a pursuit of a life of freedom and dignity, a defiance of its political powerlessness, a protest at its humiliation.

The violence/counter-violence binary also affords ambivalence. An off-duty armyman’s killing, a policeman’s lynching, the killings at Amarnath. Moments that give you pause, moments of doubt, reflection, internal debate, speculation. Civil society spoke out, even those who had lost their loved ones in the summer of 2010. Kashmir held on to its humanity. Which is why the broad movement of spirit is one. And why there happens to be disseminated fairly widely the sense of a ‘just war’.

Advertisement

(The writers are political science students at Kashmir University)