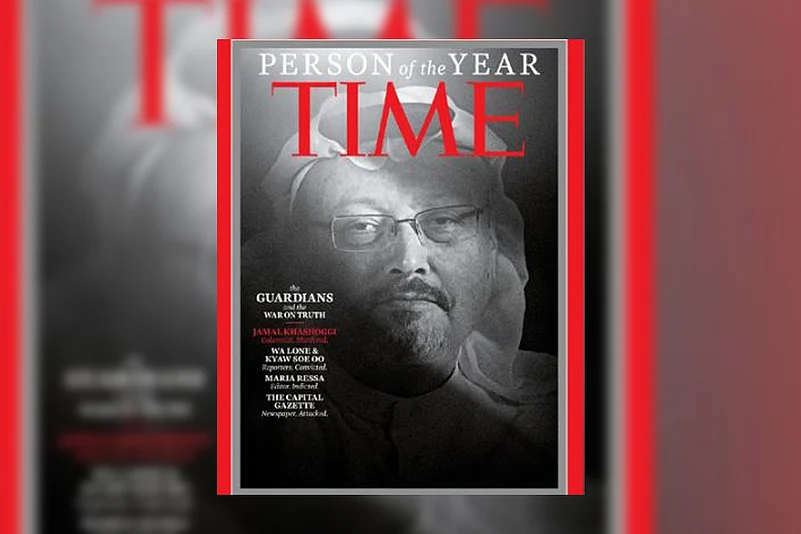

Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, who was murdered at the Gulf Kingdom's consulate in Istanbul in October, and three other journalists were named TIME's Person of the Year, an honour that recognises them for "taking great risks in pursuit of greater truths" and "for speaking up and for speaking out."

Time Magazine Tuesday said this year it is recognising four journalists and one news organisation who have paid a terrible price to seize the challenge of this moment: Khashoggi, Philippine journalist Maria Ressa, two young Reuters reporters Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo - currently imprisoned in Myanmar - and the Capital Gazette in Annapolis, Maryland, where five journalists were gunned down.

Advertisement

"For taking great risks in pursuit of greater truths, for the imperfect but essential quest for facts, for speaking up and for speaking out, the Guardians — Jamal Khashoggi, the Capital Gazette, Maria Ressa, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo — are TIME's Person of the Year," the magazine said Tuesday.

"They are representative of a broader fight by countless others around the world - as of December 10, at least 52 journalists have been murdered in 2018 - who risk all to tell the story of our time," Time said.

On Khashoggi, the magazine said that the Saudi journalist "dared to disagree with his country's government. He told the world the truth about its brutality toward those who would speak out. And he was murdered for it."

Advertisement

"Khashoggi had fled his homeland last year even though he actually supported much of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s agenda in Saudi Arabia. What irked the kingdom and marked the journalist for death was Khashoggi’s insistence on coming to that conclusion on his own, tempering it with troubling facts and trusting the public to think for itself," Time said.

Ressa, founder and editor of a Philippine news site, Rappler, has faced a barrage of government lawsuits aimed at the site, and violent hate messages on social media - at one point, 90 of them an hour.

Rappler has chronicled the violent drug war and extrajudicial killings of President Rodrigo Duterte that have left some 12,000 people dead, according to a January estimate from Human Rights Watch. The Duterte government refuses to accredit a Rappler journalist to cover it, and in November charged the site with tax fraud, allegations that could send Ressa to prison for up to 10 years.

In Annapolis, U., staff of the Capital, a newspaper published by Capital Gazette Communications, which traces its history of telling readers about the events in Maryland to before the American Revolution, press on without the five colleagues gunned down in their newsroom on June 28.

"Still intact, indeed strengthened after the mass shooting, are the bonds of trust and community that for national news outlets have been eroded on strikingly partisan lines, never more than this year," it said.

The two Reuters reporters remained separated from their wives and children, serving a sentence for defying the ethnic divisions that rend that country. "For documenting the deaths of 10 minority Rohingya Muslims, Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone got seven years. The killers they exposed were sentenced to 10," Time said.

Advertisement

"Efforts to undermine factual truth, and those who honestly seek it out, call into doubt the functioning of democracy. Freedom of speech, after all, was purposefully placed first in the Bill of Rights.

"In 2018, journalists took note of what people said, and of what people did. When those two things differed, they took note of that too. The year brought no great change in what they do or how they do it. What changed was how much it matters," Time said.

PTI