Translator's Note

Daisy Rockwell

When the great Hindi author and satirist Shrilal Shukla passed away in October of 2011, I was approached by the editor of outlookindia.com to write a short piece about his work. I agreed, but said I might need a week. It’s now been nearly 140 weeks and I’m only now writing a few very tentative and preliminary thoughts on Shukla ji. I could give all sorts of excuses, of child care, of other deadlines and pressing concerns, but the truth of the matter is that I had not read much of Shukla––nothing more than his celebrated novel Raag Darbari––so I thought I would dip my toes in and read a bit more before I wrote something suitably knowledgable in his memory. I ordered some books, other novels, satirical essays, short stories, and began to read. And I continued to read, and kept on reading. In fact, to this day, I’m still reading Shukla on a regular basis, but I must admit I still haven’t quite gotten to the point that I feel I have a real grasp of who he was as a writer. This has less to do with my own perfectionism, or even my own dull wits (I hope), and more to do with the tremendous range of his work. Raag Darbari is something of an epic, a portrait of village India that with its vast sweep and intricate details completely overturns the utopian Gandhian ideal of village life on its head. If the heart of India lies in her villages, then her heart is very disturbing indeed, Shukla wishes us to know.

Advertisement

I went on to read other novels, expecting more of the same trenchant critique. Instead, I found a noir-ish novel set in Delhi with a female protagonist (there are virtually no women in Raag Darbari), Simaaen Tuuttii Hain; an incredibly depressing novel about an alcoholic sitar player and government servant in search of a house (Makaan); and a youthful novel of progressive idealism, (Sunii Ghaatii kaa Suraj). I started reading the short stories then, and the satirical essays. Here we find Shukla at his most trenchantly critical and humorous. I found his stories always somehow timely and fresh. A tale of a writer on retreat at a forest guest house who becomes the unwilling drinking buddy of a misogynistic forest ranger; a group of men (presumably government bureaucrats, like Shukla himself) goes hunting and accidentally shoots a young woman fleeing from her wedding day; a satirist writing a witty piece about improving attendance at one’s death procession is appalled to see an elderly man get hit by a car in front of his house.

Advertisement

In all of these, the boundary between fiction writing and essay writing is unclear. In the fictional pieces, the protagonist or narrator is often an older man, a bureaucrat or writer, just like the author himself; in his satirical essays, there are sometimes narrators or even characters that are clearly meant to be fictional. The lines are blurred, and the subjects always feel fresh and contemporary no matter when they were written. I chose this bit of satire to share on Outlook because of that feel of contemporary relevance. Shukla, or someone like him, interviews a defeated leader just after the election. The leader is clearly an R.K. Laxman-style Congress politician who has lost sight of the goals of national service. No matter where one might stand on the recent election results in India, this small essay will make you smile, or even laugh out loud, because it contains a kernel of truth. This is what makes Shrilal Shukla such an extraordinary critic of society whose relevance will stay with us for a long time to come.

***

When I arrived at his bungalow, he lay on the verandah like a piece of furniture. I stood in the field of Waterloo after the battle.

The front lawn was a scene of devastation. There were a couple of jeeps covered in dust; discarded tyres and old car parts lay scattered about. Four sets of loudspeakers and some old tattered durrees lay beneath a shed. Several bamboo poles and lathis lay about to one side, willy-nilly. There were four or five sacks under the shed as well; I couldn’t tell if they contained knives or bottles of liquor.

Advertisement

A bundle of posters rolled back and forth in the breeze, and sheets of voter rolls flapped about.

I told him I was a journalist. “I’ve already lost and left my post,” he said. “There’s nothing I can give you now.”

“You could give me an interview,” I said.

To encourage him, I added, “You’re like Napoleon. You’ve been defeated, but you’re not dead. Even if there’s nothing else you can do in this state, you can still give an interview. Look at your other elderly colleagues. What else have they given the country for several years besides interviews?”

He agreed. “Wait two minutes,” he said.“Let me get my senses in order.”

Advertisement

He was eighty-two by now, and up to now I’d been yelling into his ear. He pressed the buzzer and had his servant bring a few items. He fitted false teeth into his mouth, put on his glasses, and stuffed an earphone into his ear. As soon as he was done, he began to look just like he did in cartoons. After this, he lay on his easy chair in a pose that lay somewhere between sitting up and lying down, living and dying.

“I was very sorry to hear of your defeat,” I said.

“Several people have already said this to me,” he said, “even those who voted against me.”

Advertisement

“That’s no surprise,” I said. “Actually the public is in a sorry state. They’d be sorry whether you won or lost. What are your plans for the future?” I asked.

“Giving interviews—as you yourself already noted,” he responded.

“I understand,” I said. “But a few days ago they said in the papers that you were going to become a sanyasi and retire from politics.”

“They said wrong. Actually what I said was that sanyasis should also take up politics.”

His responses were quite sharp. It seemed that his mind was not a separate part of his body; it didn’t have to be brought in from somewhere else like his false teeth, and fitted in.

Advertisement

“So you’ll continue to take an active part in politics?” I asked

“If I’d won it would be a different matter,” he responded. “But now what do I have left but active politics?”

“You’ve been an active politician for half a century,” I asked, “you don’t get bored?”

“This is what we call service to the nation,” he said in a serious tone, and turned his face away.

“Don’t you think some room should be made now in politics for the new generation?”

He lifted his head with some effort and stared at the ceiling for a little while. Then he said, “But where is the new generation? I don’t see it anywhere.”

Advertisement

This response threw me. I repeated myself, “So in your opinion, there aren’t any young men at all?”

He was perhaps annoyed at my insistence on this question. “There may well be!” he retorted sharply. “They may well be, somewhere, but I don’t know them.”

In the same vein, I asked again, “And in your opinion there aren’t any people in the public that could…”

He said, interrupting me, “The public! There’s probably a public somewhere too! But I don’t know it.”

I fell silent, with a view to calming him down. After a bit, when he seemed calmer, I asked, “What was the reason for your defeat in the election? To what extent do you consider it a defeat of your policies?”

Advertisement

He thought for a little while. Then he said, “Look, it can’t be a defeat of my policies, because I didn’t have any policies.”

“But that’s off the record,” he added quickly.

“It’s actually more attractive to say that my policies were defeated than to say that I was defeated,” he explained. “That removes the stain of defeat.”

“So then what other reason could there be? Casteism?”

“I have no problems with casteism. I’ve won many times with the help of casteism.” He shook his head. “The real reason for my defeat is Saturn and Rahu. Policies, philosophy, the public mood—these are all just excuses. Actually I was defeated by my planets. I knew it would happen beforehand. Seven astrologers warned me that Saturn and Rahu were transiting through my twelfth house, the house of loss, and to make matters worse, Mars had them both in its sights.”

Advertisement

He stopped for a moment and then asked, “Do you believe in astrology? This is the boon given to us by our rishis. Astrological science!”

I ignored the question, and said, “Even though you’d been warned by the astrologers, you continued to fight the election?”

“There was no way to save myself from it!” he said. “Again, it’s all the rotation of the planets! Jupiter was in its exaltation in my fourth house with a benevolent eye on the tenth. In such a situation, of course I had to fight the election.”

I realized he was now about to go over each planet, but the one planet he wouldn’t set foot on was the one known as earth. I closed my notebook, thanked him, and stood up. He was still talking about astrology.

Advertisement

I interrupted him to say my final piece, “Society today is in a sorry state. They need a message of asha, of hope, from you.”

Perhaps he hadn’t quite heard what I said. He blinked and said with some agitation, “Asha? Do you know her? Where’s she living these days?”

Message received. Now there was no need to push me out.

Originally published as "Ek Haare Hue Netaa kaa Interview" in the collection Yahan se Vahan in 1969. The translation is published with permission from the author's estate.

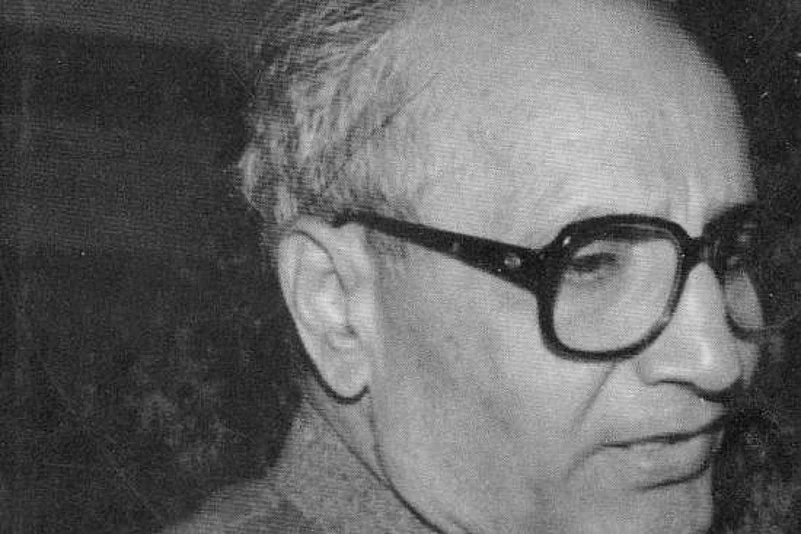

Shrilal Shukla (1925 - 2011) was among the most celebrated Hindi authors of the post-Independence era. Shukla was known for his satire and unstinting critiques of Indian life after Independence. He worked as a Provincial Civil Services (PCS) officer for the state government of Uttar Pradesh, and later became a member of the IAS. He wrote over 25 books, including the famous Raag Darbari, a satirical novel of village India with an epic sweep.

Advertisement

Daisy Rockwell is a translator, painter, and writer who lives in Vermont, USA. She has a PhD in South Asian literature and has written widely on Hindi and Urdu literature, including her book Upendranath Ashk: A Critical Biography, Katha, 2004. Rockwell has translated a collection of Ashk's short stories, Hats and Doctors, Penguin, 2013, and her translation of Ashk's novel Falling Walls is forthcoming from Penguin India in 2015. She is also the author of a novel, Taste, Foxhead Books, 2014.