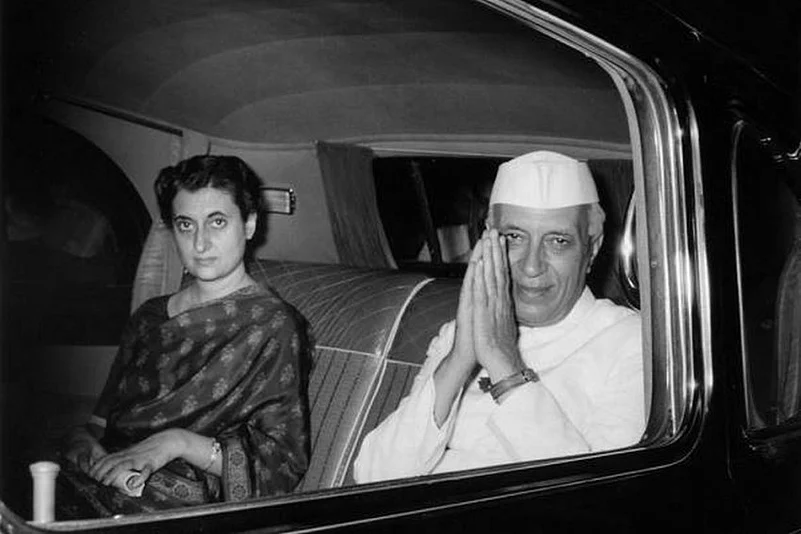

In 1955, Jawaharlal Nehru told Parliament that he had sent his daughter Indira to Pune and Shantiniketan to study so that she could understand different Indian cultures and learn various Indian languages.

The context: the Lok Sabha was discussing the linguistic reorganization of states, and even as he backed the principle, Nehru cautioned members against linguistic chauvinism and encouraged them to know a linguistic and culturally diverse India better. He also called for the protection of linguistic minorities, telling MPs that they represented not just their Lok Sabha constituencies but also India as a nation.

These were times when linguistic states were being demanded to give expression to people’s aspirations and also to facilitate administration in the local language.

Advertisement

Nehru agreed that usage of the local language was necessary for the development of an area. But he cautioned members of Parliament against linguistic chauvinism and using language in ways that divided society, offering them a lesson in nationalism from his personal life.

“This is in relation to my daughter... When she was a little girl I sent her to school, not in UP — as I wanted her to pick up India’s languages — but in Poona. I sent her to a Gujarati school in Poona because I wanted her to know the Marathi language and the Gujarati language,” Nehru told the House about the choices he made for his daughter Indira’s education. “I sent her subsequently to Shantiniketan because I wanted her to understand the Bengali background — not only the language but the cultural background.”

Advertisement

He then asked the members what they would do when states are bilingual or become bilingual over a period of time.

“There are invariably bilingual areas, and if they are not today bilingual areas, are you going to prevent people from going from one state to another?” India’s first Prime Minister sought to know. “Are you going to stop, contrary to the dictates of our Constitution, the movement of population, the movement of workers or of other people from one state to another?”

In this, Nehru addressed linguism, a tendency of mobilizing and othering on the basis of language, even as the linguistic reorganization of states was being seen as desirable both from the point of view of meeting popular demands and improving governance.

Nehru had seen linguism grow in the country during the days of the Hindi-Urdu controversy. After independence, too, there were demands for linguistic states as also a controversy over whether Hindi should replace English over time as the official language of the Union.

His words of caution aimed at not allowing attachment to language to become chauvinism, as also for appreciating different Indian languages.