India's monk-like Test batsman Cheteshwar Pujara told me the other day that he was one of the luckiest few among millions of young men to get to play for the country. He was making a valid point. A prodigiously talented batsman, irrespective of his lack of big scores of late, Pujara earned his India cap the hard way. He may have been a bit lucky as well. For, besides your talent, you need a little luck, too, to get into the Indian team.

There are also some players who feel that to have a godfather in Indian cricket is more important than being lucky. Former India leg-spinner Narendra Hirwani and middle-order batsman Pravin Amre had told me during separate interviews that they did not get too many opportunities simply because they did not have a godfather.

If you follow Indian cricket closely and are familiar with its chequered history, you will find it hard to disagree with what Pujara, Hirwani and Amre have said. The India cap has become "cheaper" in recent years, "and hence it has lost its value for some players", as Sunil Gavaskar once regretted, because almost every Tom, Dick and Harry finds himself in the Indian team, either for the Tests or the ODIs, or both, regardless of the quality of his cricket or the level of his skills. Some of them owe a sense of gratitude to their godfathers, who keep sprouting up in Indian cricket from time to time.

There is such a cut-throat competition for virtually every place in the Indian team that certain forces, including influential players, ensure that only an X or a Y cricketer gets in. There is also a big "jealousy" factor that keeps some players away from the Indian team despite their genuine potential. Several India players, who could have had longer careers, have told me, requesting anonymity, they were denied opportunities in the 1980s by a prominent player, who was monopolising in his discipline and did not want others to achieve success in that department and overshadow him a bit.

This is a dirty, vicious practice some established, influential players love to indulge in. Consequently they ruin several budding careers. We critics conveniently call it petty politics that is rampant in Indian cricket since time immemorial. Former Maharashtra player Abhijit Kale was not totally off the mark when, a few years ago, he had accused a certain set of selectors in no unambiguous terms of demanding money from him to get selected in the Indian team.

For all his greatness and all-round achievements, Vinoo Mankad was all but a gentleman cricketer. He was known for spitting expletives on and off the field, including at his teammates if they misfielded or dropped catches off his bowling. He was often accused of being "jealous" by some of his contemporaries.

Nyalchand Shah, a beautiful left-arm spinner in the classical mould who played only a solitary Test in the early 1950s, once told me an interesting but sad story about Mankad. "Whenever we used to play together for the West Zone, a jealous Mankad would tell the Mumbai players to misfield and drop catches off my bowling," said the former Saurashtra player. "Mankad obviously felt threatened by my talent."

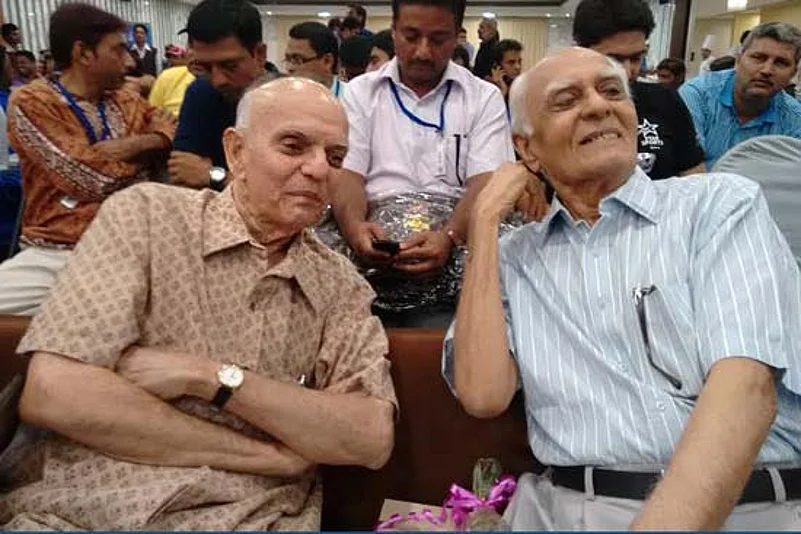

Just a few weeks ago, Deepak Shodhan (86), who scored a century on debut against Pakistan at Eden Gardens, Kolkata, in December 1952, but did not get to play more than three Tests in his career, also revealed how a "jealous" Mankad used to play "dirty politics" with the players he did not like for whatever reasons.

"I was batting at No. 8 on my Test debut and was trying my best to stem the rot after the early collapse of the Indian innings. I learnt later that a jealous Mankad had instructed a couple of lower-order batsmen to throw away their wickets in order to deprive me of my hundred," he told me recently during a freewheeling conversation while going down the memory lane. "But Ghulam Ahmed, who was the last man in, was a gem of a person. He reassured me that he would stay at the wicket, blocking one end, and ensure that I complete my century, which I eventually did by hitting two fours in a row."

Though Lala Amarnath was India's captain, it was Mankad who was calling the shots, Shodhan alleged. The octogenarian Shodhan continues to squarely blame Mankad for his brief Test career. He suspected that Mankad had developed a "strong dislike for Amdavadis" after he was sacked by an Ahmedabad businessman who, the story goes, had offered him employment in his firm.

The plight of Madhav Apte (82), another batsman with oodles of talent, was more or less similar. Bright future and a great career seemed to beckon this magnificent Mumbai player after he scored 64, 52, 64, 9, 0, 163 not out, 30, 30, 15 and 33 for an impressive aggregate of 460 runs at a healthy average of 51.11 in the five-Test series on the 1953 tour of the West Indies. (He had earlier played two Tests against Pakistan and made 82 runs in three innings while remaining unbeaten once.)

Apte was only a shade behind Polly Umrigar but far ahead of the more experienced Vijay Hazare, Vijay Manjrekar, Pankaj Roy and, of course, Mankad both in aggregate and average. But the bitter truth — actually one of the biggest mysteries of Indian cricket — is that he never played an official Test after the West Indies tour. And he was only 22.

A thorough gentleman who played cricket in the right spirits throughout his life, Apte took everything in his stride and never pointed a critical finger at anyone for his curtailed Test career. But he has revealed something truly shocking, more than sixty years after the West Indies tour, in his recently published autobiography, As Luck Would Have It.

"My sudden disappearance (exit) from Test cricket, especially after an impressive record, was never explained. Lala Amarnath chaired the selection committee. During the second Test in Bombay, curiously he approached me with a request to meet my father. He wanted cloth distributorship of the Kohinoor Mills for Delhi. He came home to meet my father. Bhausaheb (Apte Sr) was shrewd enough to put two and two together! He and me, both of us would never have liked to link my cricket career and business," Apte writes in the book.

"He politely declined Lala's distributorship proposal! Lala continued to be the chairman of selectors for a few years! I was never selected to play Test cricket again!"

I had a chance meeting with Apte during a sporting event, where he was the chief guest, in Ahmedabad in the first week of June. I could not help asking him if he harboured any ill will towards anybody. "I have not yet comprehended why I was dropped for no apparent and convincing reasons," he said. "But I have forgotten everything. All that is past now. And I have no negative feelings whatsoever for any particular individual."

There has not been much of a change in Indian cricket after all these years. You do not have to go too far in the past. A number of cricketers of the more recent vintage, who did not get many opportunities in spite of their potential and the resultant performances, may have startling tales to tell about the scurvy treatment meted out to them. But they will not come out in open and reveal all for fear of inviting the wrath of BCCI, which is looking after the retired and semi-retired (those players still playing first-class cricket with little or no chance of donning the national colours again) cricketers rather too well. However, the fact remains that they do feel being victimised in some way or the other.

Games Godfathers Play

A story or two of talented Indian cricketers, luck, jealousy, godfathers, petty politics and victimisation.

Advertisement

Games Godfathers Play

Games Godfathers Play

- Previous Story

Lucknow Super Giants Vs Chennai Super Kings, IPL 2024: Three Key Player Battles To Watch Out For

Lucknow Super Giants Vs Chennai Super Kings, IPL 2024: Three Key Player Battles To Watch Out For - Next Story