The discourse on Asia's so-called rise is dominated by comparisons of China and India, countries whose vast populations and buoyant economies have captured the imagination of international investors, journalists and policy analysts. Indeed, the India-China comparison is a virtual industry, born aloft on a river of books and reports that rely on florid bestial analogies featuring casts of tigers, elephants, dragons and tortoises.

"Chindia"-scented rhetoric abounds with catchphrases that state the obvious, but whose import is less so. China has the hardware, India the software; India needs China's roads, China could do with India's political inclusiveness. Given how fundamentally different India and China are, though, these kinds of "lessons learned" (complete with PowerPoint presentations) are of limited value. An apple cannot become an orange simply because a McKinsey or Deloitte report asserts it would be beneficial for it to do so.

Advertisement

Two's Company

The more relevant comparison in Asia — and one with enormous implications for the global economy — is between India and its civilisational sibling, Indonesia. These two eclectic democracies have more in common than India and China, yet they are rarely hyphenated.

While China's per capita GDP in 2013, adjusted for purchasing-power parity, was $9,600, the equivalent for India was a mere $4,000, putting it much closer to Indonesia's $5,200. China's investment in fixed capital in 2013 accounted for 46 percent of its GDP, compared to only 30 percent in India, a figure that is again more comparable to Indonesia's 33 percent. China is the global leader of merchandise trade, boasting well over a 10 percent share of the world total, while India's share is only 1.6 percent and Indonesia's is 1.0 percent.

Advertisement

On parameters of human development ranging from sanitation to malnutrition, India and Indonesia are once again closer to each other than they are to China. For example, around 37 percent of children under the age of 5 in Indonesia and 39 percent in India are stunted (that is, shorter than the World Health Organization's reference population) from malnutrition and related factors, compared to less than 10 percent in China.

A list of the fundamental challenges confronting India today could just as well be Indonesia's. On the economic front, both nations need to boost manufacturing competitiveness to create the millions of jobs required to ensure their young and growing populations become a demographic dividend, rather than a Malthusian disaster. Both have governments that must attract foreign investment and fix creaky infrastructure, even as they assuage protectionist lobbies and battle entrenched corruption. Weak governance plagues both nations, as both Delhi and Jakarta continue to struggle to balance power between the center and provinces.

"Bhinekka Tinggal Ika" (multiple but one), the Indonesian national motto, is in essence identical to the Indian catchphrase of "unity in diversity," and they underscore the nations' comparable accomplishments in having managed to sustain national identities in societies fractured along ethnic and religious lines. Nonetheless, ensuring the rights of minorities remains a fraught undertaking for both countries.

China's problems are, for the main part, of a different nature. The country already boasts world-class infrastructure. It is an established manufacturing powerhouse and became the world's largest recipient of foreign direct investment in 2012. China's demographic problems look more like those of highly industrialised countries with their aging populations, low fertility rates and contracting labour forces.

Advertisement

With a single official language (India has 23), standardised written script, one major ethnic group, and political tendency (both past and present) toward imposing uniformity, China is also a more homogeneous nation in ethnic and religious terms than India or Indonesia. While China does not have a national motto, tianxia ("all under heaven") is a dictum long associated with the Middle Kingdom that stresses the complete political sovereignty of the Chinese emperor over all the land "divinely" ordained for him. It illuminates the strong centripetal tendency that has been, and still is, fundamental to the Chinese polity.

Unlike India or Indonesia, contemporary China is preoccupied with foreign policy issues and the pressing of territorial and maritime claims. Economically, it needs to move up the value chain from a manufacturing hub to a services leader and an innovation center. Politically, China's leaders are focused on "stability" — a euphemism for ensuring the Communist Party's monopoly on power.

Advertisement

Connections

An Indian's first reaction to China is often bewilderment. The language is wholly alien in sight and sound. The scale of the architecture seems outlandish. The highways are impossibly smooth, and the winter cold frighteningly desolate. Despite the fact that the days of everyone dressing in identical Mao suits are long over, there is an underlying uniformity to the physical and intellectual lives of the Chinese that is unfamiliar to Indians.

Every big Chinese city has identical glittering glass-and-chrome malls. Smaller towns use bathroom tiles as their construction material of choice. The heated political debates that are par for the course aboard Indian trains are absent; the pageantry of street demonstrations and strikes is missing. Calls to prayer and the ringing of temple bells are rarely part of the aural backdrop.

Advertisement

Indonesia, on the other hand, is immediately familiar to an Indian. Regular demonstrations, featuring protestors who range from workers clamouring for a higher minimum wage to religious hardliners demanding the cancellation of beauty pageants, cause massive gridlock on the roads. Little retail shops selling everything from candy to talcum powder shelter in the shade of the extravagant malls. The call of muezzins punctuates the day, while the smell of moist earth emanate from gardens.

Everywhere — embedded in the language, on street signs, in political commentary and on bus advertisements — are references to the Hindu epics of the Ramayana and Mahabharata. An enormous statue of Krishna leading Arjuna into battle dominates the roundabout in front of Monas, Jakarta's main nationalist monument. Even Indonesian Muslims are commonly named after Hindu gods and goddesses. Among the country's favorite forms of mass entertainment, particularly on the populous island of Java, is wayang kulit, shadow-puppet theatre that features tales from the Indian epics.

Advertisement

Consequently, it remains common in both countries to express values like courage, strength and honesty with allusions to characters from Hindu stories. Even relatively hard-line Islamic political parties like the Partai Keadilan Sejahtera (PKS) have been known to hold wayang performances to boost their electoral fortunes. At a party convention held in Jogjakarta in 2011, for example, the PKS staged scenes from the life of Bima (a Mahabharata hero) to claim the need for a Bhima-like entity (the PKS itself ) to fight corruption.

The explanation for this affinity (it was not wholesale but tempered and modified by indigenous culture) is that for centuries, Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms ruled over large parts of the Indonesian archipelago. And Hindu cultural norms continued to infuse indigenous mores, even after large-scale conversion to Islam in the 16th century.

Advertisement

Colonial rule — British in India's case and Dutch in Indonesia's — disrupted many of the direct links between Indian and Indonesian kingdoms. Long established trade routes along which textiles, spices and ideas had travelled for centuries were gradually taken over by European powers from the 17th century on.

India and Indonesia both gained their independence in the late 1940s, but the turn toward economic isolationism that characterised decolonisation in both only cemented the colonial disconnect. As a result, Indians and Indonesians today are generally unaware of their strong cultural ties. Yet, the India-Indonesia hyphenation is a reality that finds present-day resonance not only in value systems, but in language. A large percentage of the vocabulary of Bahasa Indonesia, a standardised form of Malay, derives from Indian languages, including Sanskrit, Tamil and Urdu.

Advertisement

Similarity in Diversity

China has long been a more territorially coherent entity than India or Indonesia. The geographical boundaries of China over the centuries have been mutable, but what we call "India" and "Indonesia" arguably did not even exist as political entities until the colonial period. Well into the second half of the 20th century, many Western commentators believed that post-colonial balkanisation was inevitable for both, given their eclectic mixes of languages, ethnicities and religions. India, the world's largest democracy, is a Hindu-majority country — but is home to almost as many Muslims as Pakistan, in addition to substantial numbers of Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Zoroastrians. Contemporary currency notes have the denomination written in 15 languages.

Advertisement

Indonesia's remarkable diversity is less widely understood. With 250 million citizens, it is the world's fourth-most-populous nation and third-largest democracy. Superimposed on the map of Europe, the Indonesian archipelago would span the distance from Ireland to the Caspian Sea. It is home to 719 languages, spoken by people from over 360 ethnic groups (although, unlike India, it does have a national language: Bahasa Indonesia).

Seven out of eight Indonesians self-identify as Muslims, implying that more Muslims live in Indonesia than in any other country. The state, however, also recognises five other religions: Hinduism, Buddhism, Protestantism, Catholicism and Confucianism.

India and Indonesia have grappled with secessionism on their peripheries for decades, but have nonetheless survived decolonisation almost intact. They have consequently defied the European concept of the ideal nation, in which a single religion, language and ethnicity is assumed to be the "natural" basis for a sustainable political state.

Advertisement

That India and Indonesia have not only endured but are among the fastest growing economies in the world today is a testament to the fact that it is possible to create a strong, common identity out of seemingly irreconcilable multiplicity. That they are able to calibrate such diversity within a democratic political system (Indonesia has been a democracy since the downfall of military dictator Suharto in 1998) is an achievement that sets them apart from China.

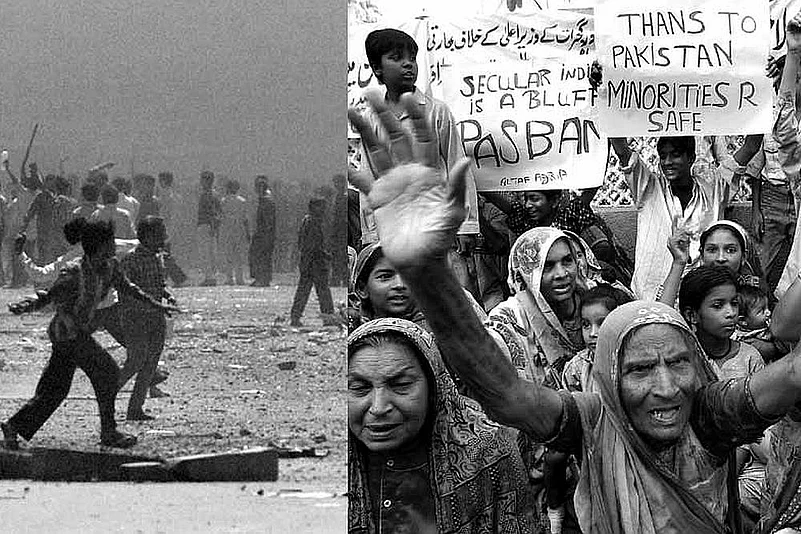

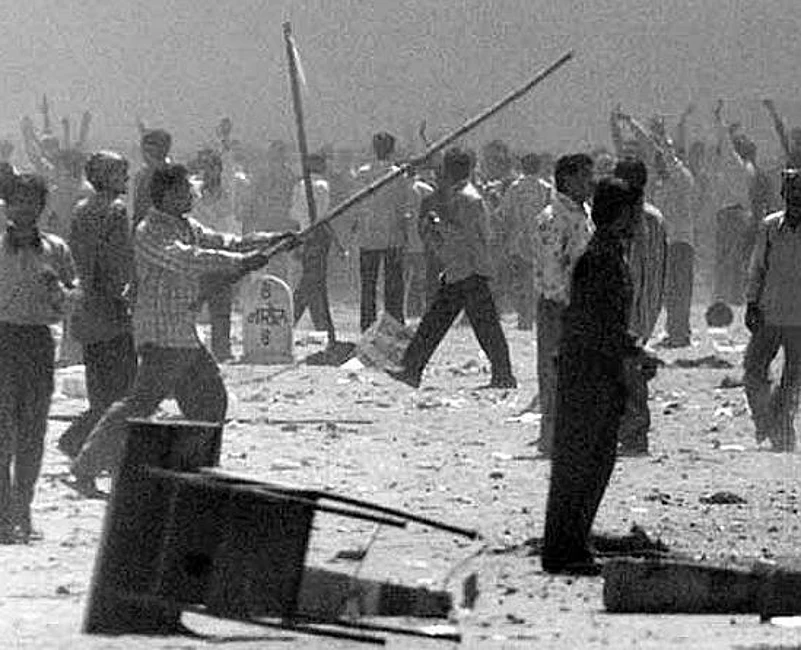

However, both countries face major challenges in ensuring that democracy does not turn into the tyranny of the majority. Narendra Modi (India's current prime minister), who is widely hailed as an economic reformer, also stands accused of doing little to stop the 2002 religious riots that took place under his watch as chief minister in the State of Gujarat. More than 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, were killed.

Advertisement

Modi denies that he was complicit and has been cleared by the courts; nonetheless, many civil-society groups continue to hold him culpable. Modi's political party is also closely affiliated with the right-wing Hindu organisation, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, whose objective is to establish India as a Hindu nation. Thus India's pluralism cannot be taken for granted.

Indonesia's new leader, Joko Widodo (popularly known as Jokowi), has stronger credentials among his country's minority communities. When he ran for governor of Jakarta in 2012, for example, he chose Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, a Christian of Chinese descent, as his running mate. Yet, minority Muslim groups, including Shia and Ahmadiyah, continue to protest discrimination at the hands of the majority Sunni Muslims. Christian groups have also complained about difficulties in acquiring permits to build churches.

Advertisement

India and Indonesia eschewed theocracy as the basis for nation-building. Nonetheless, unlike in secular Europe, religion has an active place in the public life of both. As a result, they constitute important experiments in developing a third way for countries in which religion remains a central part of the identity of most citizens, but where the more intolerant aspects of religion are held in check.

The preamble to India's constitution asserts that it is a secular state. However, neither the constitution nor its laws define the relationship between religion and state. Instead, secularism is understood as respect for all religions.

Advertisement

Indonesia's constitution leaves out the word secular altogether. The founding doc trine of Pancasila, which forms the basis for the constitution, professes a "belief in the divinity of the one God." But by leaving out any reference to a specific God (in the face of opposition from Islamists who had wanted a concrete mention of Allah), the Indonesian constitution also protects freedom of religious belief and practice.

As India and Indonesia feel their way forward into the new millennium, there is inevitably confusion about their founding ideas. Conceptually, both nations are works in progress, rather than polished accomplishments. But this only underscores how germane their experiences are for each other.

Religion remains a political force in each, even as development and fighting corruption have emerged as vote-winners. If the economic growth promised by the new governments in Delhi and Jakarta fails to materialise, it is possible that leaders, especially Modi, will fall back on stoking religious rivalries as a strategy aimed at the next elections. It is unclear, though, how voters would respond to such tactics.

Advertisement

This piece was written in collaboration with Tan Chin Hwee and was first published in the Milken Institute Review. Pallavi Aiyar is an author and journalist based in Jakarta. Chin Hwee Tan is a founding partner in Asia of Apollo Global Management.

The second part of this essay will appear on Sunday, August 2, 2015.