India's energy requirements already rank amongst the world's highest. India's economy has grown in fits and starts since an acute foreign exchange crisis in 1991 promoted the government to start unshackling the economy. India's real GDP grew by an average of 5.6 percent a year in the 1980s, and by 5.8 percent a year from 1991 to 2003. A growing population and rapid industrialization has prompted a sharp increase in India's energy needs. With plenty of domestic coal reserves, but not enough oil and gas reserves, India's policymakers are scrambling to bridge this energy shortfall.

Already ranking sixth in global petroleum demand, India meets 70 percent of its needs through crude oil imports. By 2010, India is projected to replace South Korea and emerge as the fourth-largest consumer of energy, after the United States, China, and Japan.

As a result, the Indian government is investing heavily to secure supplies from abroad. Last week, Oil & Natural Gas Corp. (ONGC), India's largest state-run oil explorer, won the right to develop Qatar's offshore Najwat Najem oil field with an initial investment of US$20 million. During Chavez's visit, India and Venezuela signed six agreements, mostly dealing with energy trade. While two Indian companies will take a 49 percent stake in a Venezuelan oil field, Venezuela's state-run oil company, will invest in one of India's refineries. In addition to Russia, Latin America, and the Middle East, Indian oil companies are looking to African countries – Chad, Niger, Ghana, and Congo in particular – for oil and gas fields. A recent a high-profile conference of oil-producing countries in New Delhi gave Indian officials a chance to scout for more opportunities worldwide.

Indian authorities have indicated that they are also not hesitant in seeking deals with pariah states. InSudan, India has invested US$750 million to pick up a 25 percent equity previously held by the Canadian Talisman Energy in the Greater Nile Oil Project. (The Canadian company was forced to quit Sudan after it came under pressure from human rights organizations on the charge of committing genocide in Darfur region.) Closer to home, India has reached an agreement with Myanmar's junta for the construction of a gas pipeline.

Advertisement

Forging alliances with oil-producing countries comes with its own risks, since these states are often in conflict with the United States over human rights or non-proliferation issues. Sudan, for instance, has been criticized for gross human rights violations in the Darfur region and may even come under UN Security Council sanctions. Myanmar's military rulers are under pressure from the international community for imprisoning and torturing activists demanding a return to civilian rule. US-Venezuelan relations are bitter over an alleged American plot to overthrow Chavez. Washington will probably tolerate India's alliances with these nations, as long they remain strictly trade-focused. Anything further will invite US displeasure and possibly strain relations between the two countries.

The thirst for energy has also pushed India to adopt a more pragmatic approach in its conduct of foreign policy with her close neighbors. While India and China are beginning to compete more fiercely for energy assets worldwide (most recently, India lost a bid for Angolan oil to China - see "Oil Fuels Beijing's New Power Game", there is also plenty of collaboration. For instance, China Gas Holdings has established an alliance with India's largest energy conglomerate. The two countries are collaborating in places like Sudan, Russia, and Iran to feed their respective energy requirements.

Advertisement

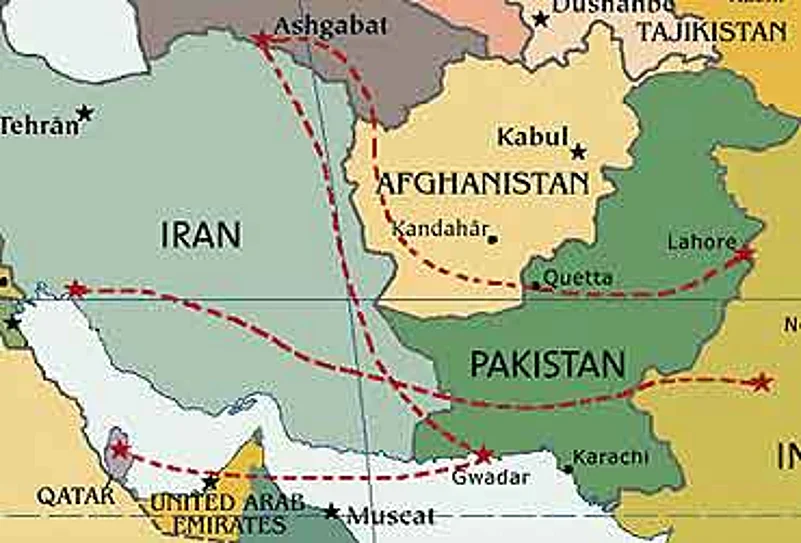

Also, after years of expressing reservations, policymakers in New Delhi have indicated their consideration of a proposal for a pipeline from Iran to India, via Pakistan. While Pakistani authorities have promised not to interfere in gas delivery to India and agreed to guarantee the security of the project, decades of mistrust and the threat of Pakistani extremists damaging the pipeline prompted the Indian side to go slowly. The gas pipeline could bind the two rivals in an economic relationship, which will be hard for either side to break. It could also accelerate the promising steps taken by both sides recently to solve their outstanding issues.

India's growing ties with Iran, however, raise a number of interesting questions, given India's good relations with Israel and the United States. By far, India's biggest success overseas has been in Iran where the Indian Oil Corp., a state-run company, reached a January 2005 agreement with the Iranian firm Petropars to develop a gas block in the gigantic South Pars gas field, home to the world's largest reserves. India is cooperating with President Mohammed Khatami's government to secure Persian Gulf sea lanes and formulate a common Central Asian strategy. India is also helping Iran to develop its Chahbahar port, as well as several infrastructure projects.

Indian policymakers tend to downplay military relations with Iran, but New Delhi's strategic relations with Tehran do have worrisome components for US policymakers: According to a recent report from the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) titled Iran's Developing Military Capabilities, Iran sought India's help in developing batteries for its submarines, which are more suitable for the warm waters of the Gulf than those supplied by Russia. Washington and Tel Aviv are concerned about Iran's power projection capability offered by the submarines. On the nuclear issue, India is very cautious to keep its distance from Iran for fear of upsetting foreign policy hawks in Washington, although it has claimed it has helped Tehran with generating nuclear energy. Israel is also keeping a cautious eye on this budding relationship and will probably remain quiet – as long as the connection does not become overtly military in nature.

The growing economic ties between and India and Iran are moving in the opposite direction from Washington's continuing effort to isolate the Tehran regime. India and the US have agreed to identify ways to cooperate in preventing the further spread of nuclear technology as part of their Next Steps in Strategic Partnership. But signing long-term deals with Iran would make it hard for India to oppose Iran if the matter came up to the UN for sanction.

Though India's increasing energy requirements will continue to push the country in a new direction – which often won't be welcomed in Washington – it obviously won't be the only factor. Washington has already expressed its displeasure at New Delhi's new-found friendship with the regime in Tehran. India's long-term strategic interest is better served by maintaining and improving upon its good relations with the United States, which will be a crucial source of capital and technology and a potential ally should relations with China turn sour. These requirements will force Indian diplomats to carefully craft these nascent oil alliances and resist from providing any support militarily.

Advertisement

Pramit Mitra is a Research Associate with the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C.This article appeared in YaleGlobal Online, a publication of the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization, and is reprinted by permission. Copyright © 2005 Yale Center for the Study of Globalization