BRUSSELS: The proposed French law banning the Islamic headscarf and other "conspicuous" religioussymbols in schools and public administrations has brought to the surface the uncomfortable issue of the roleof minorities in European societies. Not all of France's neighbors share the country's passionate commitmentto secularism and the republican ideal of a strict separation between church and state, arguments used by theFrench government to demand the headscarf ban. But many are equally afraid of the veil as a symbol of risingmilitancy among Muslim communities.

The anguished French debate over the Islamic veil and the "threat" it poses to Westerntraditions, including the principles of gender equality, looks set to be repeated in Belgium, Germany, Spainand the Netherlands.

Advertisement

Europe's political rhetoric over the sartorial choices of Muslim women is misplaced, however. Instead offretting over the veil (and, as was suggested recently by French Education Minister Luc Ferry, Islamic beardsas well as the bandanas that Muslim girls might wear to circumvent the ban), European politicians should betackling the real problems of discrimination, hostility and isolation facing almost all of the continent's12.5 million Muslims. It is this isolation that has encouraged some to embrace a more rigid interpretation ofIslam.

Painfully missing from Europeans' discussions on Islam is any recognition that Muslim immigrants are anintegral part of Europe, that Islam is part of Europe's historical heritage and its present. Muslim workers,mainly from Morocco, Turkey, Algeria, Tunisia, West Africa, and South Asia, continue to play a crucial role inEurope's economic development.

Advertisement

Unlike the urban professionals - doctors, engineers and IT experts - who make up a majority of Muslims inNorth America, Europe's Muslim immigrants are largely from poor, rural backgrounds and have come to thecontinent to labor in coal mines and steel mills. Some have climbed up the social ladder but a large majoritystill remains on the margins of society, ignored by politicians and business leaders and facing discriminationin housing, schools and labor markets. Instead of easing integration of Muslims into mainstream Europe, theFrench national assembly debate on the ban starting on February 3 risks deepening the divide.

Even more dangerously, it also threatens to aggravate post-September 11 Islamophobic sentiments in Europe.With regional and European Parliament elections set for this spring in most EU states, there are fears thatthe debate could further spur the popularity of Europe's unashamedly Islamophobic and xenophobic far-rightparties. In particular, Jean-Marie Le Pen's Front National in France is seeking to consolidate the gains itmade in the 2002 presidential election.

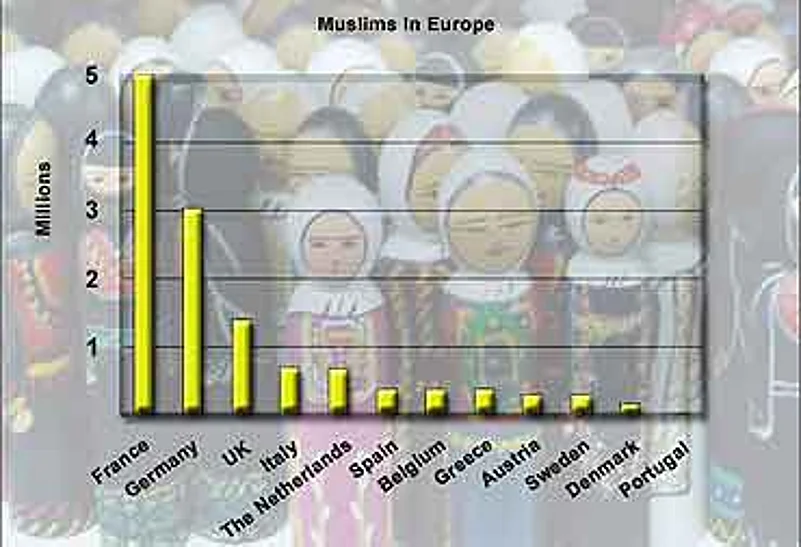

France may have the largest number of Muslims - about 5 million - but it is by no means the only Europeancountry facing the challenge of integrating its Muslims.(See chart) Demands for new Belgian legislation to banIslamic headscarves in the country's schools, courts and public administrations has triggered a majorpolitical row, splitting the small country of 10 million people, which includes an estimated 400,000 Muslims.

Belgian Foreign Minister Louis Michel warned recently of "the development of a sort ofpseudo-fundamentalist trend which could end up encouraging a miniature clash of civilizations inBelgium." Michel has also denounced the veil as a symbol of the submission of women.

Advertisement

Germany appears heading for an equally emotional confrontation. Berlin's highest court ruled last Septemberthat veils were allowed unless existing legislation said otherwise. But the states of Lower Saxony as well asBavaria and Baden-Wuerttemberg are working to introduce laws banning the headscarf for schoolteachers. Allthree states have said they are targeting the headscarf as a political symbol to avoid it from being equatedwith the Christian cross.

Channeling the debate into a more constructive discussion on integration remains a painful challenge. TheFrench discussion over the headscarf is a "false one," argues Betoule Fekkar-Lambiotte, aFrenchwoman of Algerian descent and a former member of the country's Council of the Muslim Cult, set up byPresident Jacques Chirac in spring 2002. "The real problem facing France is acceptance of Islam, of newpractices, of adapting to 21st-century realities," she says.

Advertisement

French politicians remain adamant that Muslims must play by the state's republican rules, disregardingIslam's mix of religion, state and society. But Muslims in France have difficulty identifying with theprinciples of "liberty, equality and fraternity" when the ideals are clearly not applied to them,argues Fekkar-Lambiotte.

Neither France nor its neighbors have done much to engage their Muslim minorities, allowing a more militantversion of Islam to gain favor among the most disaffected and younger members of the community. YoungerMuslims are now much readier to proclaim their Islamic identity than their parents and also more likely tofall under the sway of largely foreign-trained imams espousing the strict Islamic traditions of Saudi Arabiaand other Islamic nations which are far from the realities of life in Europe.

Advertisement

The veil is seen as the most visible symbol of this radicalization. It is also a question of women'srights, says Vincent de Coorebyter, director of Belgium's Centre for Socio-Political Research. "The veilis seen as a sign of discrimination," he says. Muslim women, especially those who wear headscarves, areviewed as victims of a repressive religion and culture. European feminists and politicians shrug offsuggestions that the veil can be a fashion statement, a legitimate expression of a new 'girl culture', or thatnot all women who opt for the veil are being forced to by their husbands, brothers, or fathers. In ironiccontrast to the effort to 'emancipate' Muslim women, young Muslim men continue to be the target of jobdiscrimination, French police prejudice, and public distrust.

Advertisement

Integration is a two-way street, however. While European governments have clearly failed to give Muslims astake in society, Muslim communities also need to do more to break their isolation. Largely disorganized anddivided, Europe's moderate Muslim majority has been unable to present its case effectively to Europeangovernments. As a result, the debate has been hijacked by a minority of radicals, says Fekkar-Lambiotte whoresigned from the French Muslim Council last year because she said it was being taken over by Islamists."What we need is a counterweight" to the militants, she insists.

Signs of changing government attitudes are emerging. Arguing that dialogue rather than confrontation isrequired, Belgium's minister for social integration Marie Arena has promised to hold a series of"inter-cultural" encounters to discuss the veil and other issues. After years of rejecting anysuggestions that Muslims need affirmative action programs to advance in society, France appears to be changingits stance and has even appointed its first Muslim, Aissa Dermouche, as prefect in Jura.

Advertisement

More is clearly needed, however. The French move to ban headscarves may be misguided, but it has finallysucceeded in spotlighting the many challenges facing governments and Muslims as they struggle to come to termswith Europe's new multi-cultural and multi-religious realities. But the sensible solutions necessary to allowharmonious co-existence will require a broadening of the current debate on the Islamic veil. Europe's Muslimsare not going anywhere: the continent is their home.

Shada Islam is a Brussels-based journalist specializing in EU trade policy and Europe'srelations with Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. This article appeared in YaleGlobalOnline, a publication of the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization, and is reprinted bypermission. Copyright © 2004 Yale Center for the Study of Globalization.