JUST A FEW YARDS DOWN THE ROAD FROM THE ICONIC EDEN Gardens Stadium in Calcutta and not too far from the free-flowing Ganga is the Mohun Bagan football ground. Step inside the gates and into the members' area opposite the stadium and you are greeted by a large poster with a grainy picture of footballers posing with a trophy. It's the eleven that created history in 1911 by becoming the first Indian team to win the IFA Shield—the blue-ribbon event of the time—by defeating a British regimental team. That momentous event of 1911, ironically the same year the capital of British India was moved out to Delhi, capped nearly four decades of efforts at physical regeneration by Bengalis to shake off the "effeminate" tag bestowed by the British. This was contrasted with the "manly" Englishman as well as the so-called martial races such as the Punjabis, Marathas, and Pathans. The classification was backed up by pseudoscientific studies by colonial officials like Herbert Risley, who believed that Bengalis could be "recognized at a glance" and that climate and diet contributed in great measure to the Bengalis' poor physical condition.1

Advertisement

We began this book with an unflattering description of a Bengali by an English journalist. Such views were hardly uncommon among British officials, including such famous figures like Thomas Babington Macaulay, who, among other things, shaped the education policy in India. Among the many disparaging things Macaulay had to say about Bengalis (and indeed Indians in general), the one that stood out was "The physical organization of the Bengalis is feeble even to effeminacy... His pursuits are sedentary, his limbs delicate, his movements languid." 2 Even more priceless was a British journalist's characterization of a Bengali's physique. According to G. W. Steevens,

Advertisement

By his legs you shall know a Bengali... The Bengali's leg is either skin

and bones... or else it is very fat or globular, also turning at the knees,

with round thighs like a woman's. The Bengali's leg is the leg of a slave.3

These barbs were aimed particularly at the Bengali babu , whose rise as a class was predicated on the political economy of colonialism but who over time organized themselves to agitate against colonial rule. The relationship between the British and the Bengalis was a curious one: the Bengalis were, by virtue of being the first group in India to have sustained contact with the colonial rulers, the most "British" of the Indian subjects. Indeed, it was their similarity to the Bengalis—in some senses their mirror image—that may have made the British so wary of them.

Bengalis quickly took to heart these criticisms about physical inadequacy and started believing them. Thus the novelist Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay could say, without any doubt, that Bengalis always lacked "physical valour," even though he had no tangible evidence of that.4 In the late nineteenth century, however, the Bengalis began to react to the constant denigration with a concerted effort to raise their self-esteem in both mind and body. Chattopadhyay himself wrote novels like Ananda Math , which introduced the patriotic slogan "Vande Mataram," asserting the need for militant resistance against foreign rule. Along with these efforts, a physical culture movement took shape in the 1860s.

Advertisement

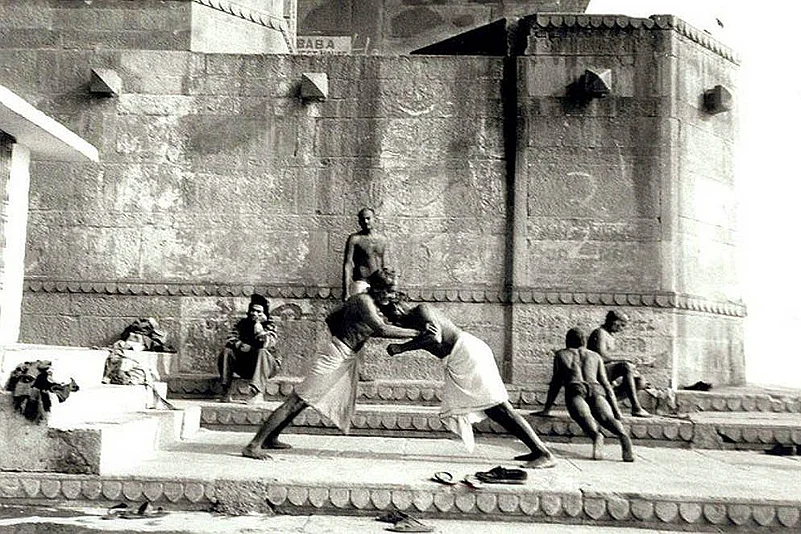

In 1866, another Bengali intellectual, Rajnarayan Basu, called for the revival of "national gymnastic exercises," 5 and a year later the Hindu Mela, which had its patrons the Tagore family, was launched. Particularly active in the Hindu Mela was Rabindranath Tagore's niece Sarala Debi. The festival had on its program wrestling, gymnastics, and other traditional sports, like stick fighting. It also aimed at breaking colonial stereotypes by pitting Bengalis against the so-called martial races. In 1878 the Sambad Prabhakar reported on a wrestling contest between a Bengali and a Punjabi in the Hindu Mela: "Even though the Bengali tried very hard to win, he finally failed, but this is not a matter of shame. Last year, the Bengali had defeated the Punjabi, this year he lost... that the Bengali has succeeded in wrestling with a Punjabi—this in itself is worthy of praise."6 One of the forces behind the Hindu Mela, Nabagopal Mitra, established an akhara , or gymnasium, in Calcutta7 and was active in recruiting physical education teachers to train the youth. The National Paper , the organ of the Hindu Mela instituted by the Tagores in 1865, talked of the need for Bengalis to train as soldiers in order to measure up to the Rajputs, Sikhs, and Marathas. As historian Sumit Sarkar pointed out, it was "natural for young Bengalis to seek psychological compensation in a cult of physical strength and a somewhat exaggerated faith in the efficacy of purely military methods."8

Advertisement

Some members of the colonial administration were keen, too, that the Bengalis improve their physical health. Sir George Campbell, lieutenant governor of Bengal in the 1870s, felt that that Bengalis were capable of great things if they set aside their "intellectual vanity"9 and their love for "literature, law and politics."10 He introduced physical fitness norms—walking and riding at a prescribed pace—for applicants to the Native Civil Service, emphasized sports in the educational institutions' curricula, and even handed out medals at a Calcutta akhara.11 At a slightly later phase, the YMCA, too, was active in this field. J. Henry Gray, who had been appointed in 1908 as the physical director of the YMCA in Calcutta, wrote that "a large number of the many varieties of physical education that are found in the world are bidding for a place of recognition or a place of prominence here."12

Advertisement

Presidency College, the oldest college in Calcutta, was a good example of the interest in physical culture sweeping Bengal. In 1879, the college started offering gymnastics classes. Nagendra Prasad Sarvadhikari, an undergraduate student at the college, along with a British professor, organized the Presidency College Corps to train students in shooting. An athletic, cricket, and football club followed, and shortly afterward, the college was granted a coveted plot of land in the Calcutta maidan. From 1897 onward, it became mandatory for first-year students to attend gymnastic classes.13 In fact, the college's football team won the Elliot Shield, the premier intercollegiate football tournament, five times between 1904 and 1908. Jitendrananth (Kanu) Roy, who represented Presidency, went on to play for Mohun Bagan.

Advertisement

Both the intellectual strand represented by Bankim Chandra and Sarala Debi and the actual physical culture movement were critical to the growth of the anti colonial revolutionary organizations in Bengal in the early twentieth century. One of the more famous such societies was the Anusilan Samity founded by Satischandra Basu in 1902 in Calcutta. An important part of the anusilan samities ' anti-British activities was physical culture and the practice of traditional sports. Yet another gymnasium was founded around the same time in Calcutta by a remarkable woman, Sarala Ghoshal, which provided training in sword and lathi (stick) play.14.

Advertisement

Such organizations flourished in the wake of the Swadeshi movement (1905–1911) and were directed against the partition of Bengal. Inspired by publications such as Bande Mataram, Yugantar, and Sandhya, scores of young Bengalis joined secret groups with the express intention of assassinating British officials and instigating armed insurrection against the colonial rulers. The anusilan movement soon spread beyond Calcutta to smaller towns. In 1906, Pulin Behari Das, an expert in lathi play, founded the formidable Dacca Anusilan Samity in East Bengal. Nirad Chaudhuri described a "physical-culture" club in his native East Bengal:

Advertisement

The greatest emphasis was placed on fencing with singlesticks... In this case the partners stood facing each other from the opposite ends of the lawn, their dhotis tucked high, the stick in their right hand, and the cane buckler in the left. They glared at each other and gave the traditional war cry of the Bengal dacoit and fighter—"hare re re re re-e-e-e-e-e-e-e-e!"15

During a later period, another prominent revolutionary formed the Simla Bayam Samity (Simla Physical Culture Club), home to several famous wrestlers, which continues to exist in north Calcutta. Swami Vivekananda, the great Hindu reformist leader, hailed from the Simla area and was said to have been tutored by Khetubabu, one of Calcutta's famous wrestlers. Vivekananda, who was an inspiration for the militant wing of Bengal's nationalist movement, was proficient in several sports: lathi play, fencing, boxing, gymnastics, swimming, and horse riding. He also once won the first prize in gymnastics in the Hindu Mela.16 But Vivekananda is perhaps best remembered for announcing: "You will be nearer to Heaven through football than through the study of the Gita," adding that one "will understand the Gita better with your biceps, your muscles, a little stronger." 17 Oddly, we have no record of Vivekananda playing football, but he was an avid cricketer, apparently even playing one match for the Town Club. 18 Unlike wrestling or body building,English team games like football and cricket provided Indians the rare opportunity to compete on a relatively level playing field and even beat the British.

Advertisement

- Mrinalini Sinha, Colonial Masculinity: The "Man ly Englishman" and the "E ffeminate Bengali" in the Late Nineteenth Ce ntury (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), 21.

- Thomas Macaulay, Critical and Historical Essays (London: Dent & Sons, 1961), 1:562.

- G. W. Steevens, In India (London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1899), 75.

- John Rosselli, "The Self-Image of Effeteness: Physical Education and Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Bengal," Past and Present 86 (February 1980): 123.

- Jogeshchandra Bagal, Hindu Melar Itibritta (Maitri, 1968), 102.

- Indira Chowdhury, The Frail Hero and Virile History: Gender and the Politics of Culture in Colonial Bengal (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1998), 22.

- Sumit Sarkar, The Swadeshi Movement in Bengal , 1903–1908 (New Delhi: People's Publishing House, 1973), 468.

- Ibid., 469.

- George Campbell, Memoirs of My Indian Career (London: Macmillan, 1893), 267.

- Ibid., 273.

- Rosselli, "The Self-Image of Effeteness," 138.

- George F. Andrews, Physical Education for Boys in the Secondary Schools of India (New York: 1934), v.

- Boria Majumdar and Kausik Bandyopadhyay, Goalless: The Story of a Unique Footballing Nation (New Delhi: Penguin, 2006), 14.

- Sarkar, The Swadeshi Movement in Bengal , 470.

- Nirad C. Chaudhuri, The Autobiography of an Unknown India (London: Macmillan, 1951), 246.