Kashmir: Recent Developments AndU.S. Concerns

Report for Congress

June 21, 2002Updated on Sep 5

Amit Gupta

Consultant in South Asian AffairsForeign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division

Kaia Leather

Analyst in Foreign AffairsForeign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division

Congressional Research Service The Library of Congress, USA

Perennially high tensions between India and Pakistan over Kashmir have hindered attempts so far to achievea sustained peace process, despite occasional moments of optimism. U.S. concern for stability in South Asiaincreased considerably as a result of the racheting up of India-Pakistan nuclear and ballistic missilecapabilities, especially since their May 1998 nuclear tests. Almost exactly one year after these tests, Indiaand Pakistan appeared on the brink of launching their fourth war in the past half-century. A two monthskirmish which began in May 1999 near the town of Kargil along the Line of Control (LOC) in Kashmir marked theworst outbreak of fighting between India and Pakistan since the India-Pakistan war of 1971. Since Kargil,tensions over Kashmir have remained high. Following a December 13, 2001 terrorist attack on the Indianparliament by militants alleged by India to have been supported by Pakistan, a chain of events ensued thatplaced the nuclear weapons states at military loggerheads. India and Pakistan have levied sanctions againsteach other, mobilized their armies and positioned missile batteries along their borders prompting the UnitedStates to embark on an intensive diplomatic effort to calm emotions and de-escalate the warlike rhetoric andmaneuvering of these two South Asian adversaries.

Advertisement

Given these dangers, United States policy in the region is geared towards reducing tensions between Indiaand Pakistan, encouraging a constructive dialogue and confidence building measures between the two countries,and working to reduce terrorism in the region and worldwide. For further details of U.S. relations with Indiaand Pakistan, see CRS Issue Brief IB93097, India-U.S. Relations and CRS Issue Brief IB94041, Pakistan-U.S.Relations). This report will be updated as circumstances warrant.

In early June, the diplomatic efforts of Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage and Defense SecretaryDonald Rumsfeld helped cool tensions between India and Pakistan that had brought the two nations to the brinkof war. Deputy Secretary Armitage was able to persuade President Musharraf to halt infiltration and todismantle the training camps in Azad Kashmir. India, in return, pulled its naval deployment, that had beenclose to Pakistani waters, back to home port. Pakistani civil aircraft were given permission to overfly Indianairspace and India, reportedly, lowered the alert status of its troops on the border. Discussions withSecretary Rumsfeld focused on a range of issues but one of the main areas concentrated on was, how to monitorthe troublesome LOC between the two countries in Kashmir. The United States reportedly agreed to providesensors, satellite photos, and unmanned aircraft to carry out monitoring.

Advertisement

Tensions between the two countries, already at a high point following the December 13, 2001 attack on theIndian parliament, had been lowering until events in May 2002 drove both countries dangerously close to war.In particular, gunmen (believed to be from Lashkar-e-Taiba) staged an attack on civilians on a bus and in thefamily housing section of an army camp in the Kashmiri town of Kaluchak, killing 32, including 10 children.India has claimed that the three assailants, who were killed by Indian security forces, were from Pakistan.Although Pakistan condemned the attacks, Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee vowed to respond withappropriate action. The attack came as Assistant Secretary of State for South Asia, Christina Rocca, wasvisiting the region in an effort to defuse the five month-long standoff between the two nuclear-armed nations.

Although many analysts have argued that the retaliatory action would probably be a limited strike againstPakistani troops across the LOC in Kashmir, others have warned that Vajpayees Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)has a domestic political interest in allowing the conflict to escalate (to draw attention away from recentviolence in Gujarat in which more than 800 mostly Islamic Indian citizens have died). Many have also arguedthat Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf has done little to prevent infiltration of religious militants fromPakistan into Indian-controlled Kashmir since his speech in January. The issue was further complicated by thereports that India would strike against terrorist training camps in Pakistani Kashmir and PresidentMusharrafs declaration that Pakistan would not rule out the first use of nuclear weapons. By late May itseemed as if the two countries might be heading towards the worlds first nuclear exchange.

Advertisement

Events within Indian Kashmir added to the confusion surrounding the India- Pakistan tensions. In mid-May,Abdul Ghani Lone, a moderate separatist belonging to the All Parties Hurriyat Conference, was assassinatedwhile addressing a meeting. Lones son initially accused Pakistans InterServices Intelligence of planningthe assassination but then backed away from the claim. Lone had called for a nonviolent settlement of theKashmir dispute and some reports claimed that he was considering participating in the September 2002 electionsto the Kashmir assembly.

There were also reports of a split within the Hizbul Mujahedeen, the main Pakistan based insurgent groupfighting in Indian Kashmir. Following an editorial in a Kashmiri daily, reportedly written by a Hizbulcommander calling for a ceasefire, the Pakistan based leadership of the insurgent group first dismissed thereport as fabricated and then went on to expel three senior commanders including Abul Dar Majid, the overallKashmir commander of the group. Dar claimed that the Pakistan based commanders were out of touch with therealities on the ground. There were also reports that Dar was considering a run for office in the forthcomingKashmir elections. But the main focus of the international community remained on preventing a war in Kashmir.

Advertisement

Introduction

For the United States, the issue with Kashmir is how to prevent an all-out war between India and Pakistanwhile concurrently maintaining Indian and Pakistani cooperation in the anti-terror campaign and keepingbilateral relations with the two nations on an improving trend. The United States also is interested inpreventing the conflict from escalating into a nuclear exchange and ensuring that nuclear weapon relatedmaterial in South Asia not be obtained by terrorists or other organizations that would be contrary tononproliferation efforts. For the long-term, the United States seeks a permanent solution to the Kashmirproblem while at the same time attempting to avoid creating a sanctuary for extremist Islamic militants.

Advertisement

Current U.S. policy on the status of Kashmir is that it should be resolved through discussions betweenIndia and Pakistan while taking into account the wishes of the Kashmiri people.

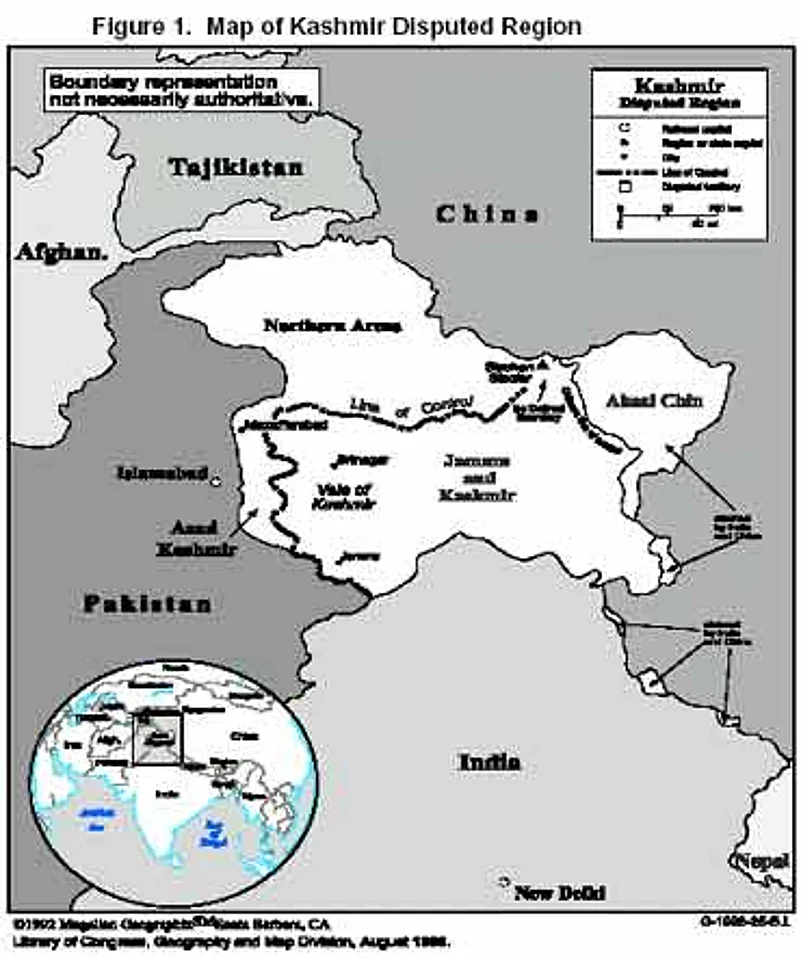

India-Pakistan rivalry dates from the 1947 partition of British India into mostly Muslim Pakistan andHindu-majority India. Claims by both successor nations to the former princely state of Kashmir have resultedin a half-century of bitter relations that has included three wars: in 1947-48, 1965, and 1971. AU.N.-brokered cease-fire in January 1949 left Kashmir divided by a military cease-fire line into the Indianstate of Jammu and Kashmir and Pakistan-controlled Azad (Free) Kashmir and the Northern Territories. Thecease-fire line was renamed the LOC under the 1972 Simla Agreement, which ended the third India-Pakistan war.In 1984, Indian troops occupied the Siachen Glacier area in the undemarcated area north of the LOC, whichsince then has been the scene of a costly, high-altitude military standoff between India and Pakistan. (Seemap.)

Advertisement

Meanwhile, India blames Pakistan for supporting a separatist movement in the Muslim-dominated KashmirValley that has claimed 30,000 lives since 1990. Pakistan maintains that it lends only moral and politicalbacking to the rebellion. Pakistan seeks international support for the carrying out of the 1948-49 U.N.resolutions that call for a plebiscite in Kashmir, by which the Kashmiri people would choose to join eitherIndia or Pakistan. India maintains that the U.N. resolutions have been superceded by various local electionsas well as the 1972 Simla Agreement, which calls for settlement of India-Pakistan differences throughbilateral negotiations. A number of the leading Kashmiri militant and political groups and their supportersfavor independence.

Advertisement

The economic and social development of both India and Pakistan and, in fact, the entire South Asiasubcontinent have been substantially held hostage by the half-century Kashmir dispute. The bitterness andsuspicion resulting from the continuing feud have led both countries to devote a comparatively largepercentage of their resources to defense, including conventional, nuclear, and ballistic missile weaponscapability. Although the Kashmir dispute is rooted in the colonial era, little progress toward resolution hasbeen made during five decades of independence. Any solution to the Kashmir issue must necessarily take intoconsideration the complex tangle of ethnic, linguistic, religious, and legal issues that surround the dispute.Above all, any settlement of the Kashmir dispute by India and Pakistan would appear to require a new level ofcommitment, political will, and leadership by the two South Asian adversaries. A major impediment to aresolution has been that many regard the Kashmir issue as inseparable from the self-definition of the twostates. Some have argued that for Pakistan, which since its inception aspired to be the homeland forMuslims in South Asia, the existence of a contiguous Muslim-majority state outside its purview underminesthe full realization of the state. For India, whose selfdefinition is as a secular nation that can accommodatea plurality of different groups, the existence of a Muslim-minority state that can live within its borders isoften considered essential to the nations credo of unity in diversity. The option of a Kashmir independentof both India and Pakistan has generally been outside the realm of consideration for the two South Asianadversary states.

Advertisement

U.S. and international concerns about stability in South Asia have increased considerably as a result ofrecent regional weapons developments. On May 11 and 13, 1998, India conducted a total of five unannouncedunderground nuclear tests, breaking a 24-year self-imposed moratorium on nuclear testing. Despite U.S. andworld efforts to dissuade it, Pakistan followed suit, claiming five tests on May 28, 1998, and an additionaltest on May 30. Responding to these nuclear tests, President Clinton imposed economic and military sanctionson India and Pakistan, as mandated by section 102 of the Arms Export Control Act. The tests created a globalstorm of criticism, as well as a serious setback for decades of U.S. nuclear nonproliferation efforts in SouthAsia.1 On April 11, 1999, India tested its intermediate-range Agni IImissile, firing it a reported distance of 1,250 miles. A few days later, Pakistan countered by test-firing itsGhauri II and Shaheen missiles, which have a reported range of 1,250 miles and 375 miles respectively. Eithercountry has the capability of targeting the major cities of the other. India tested the Agni II again inJanuary 2001 and tested a short range variant of the missile in January 2002. The United States has worked toencourage India and Pakistan to: (1) halt further nuclear testing and sign the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT);(2) halt fissile material production and cooperate in the Fissile Material Control Treaty (FMCT) negotiations;(3) refrain from deploying or testing missiles; (4) maintain and formalize restraints on sharing sensitivegoods and technologies with other countries; and (5) reduce bilateral tensions, including over Kashmir. U.S.officials have continued to urge India to resume dialogue with Pakistan, while pressing Pakistan to improvethe climate for talks.

Advertisement

The confrontation between India and Pakistan along the LOC in Kashmir in May-July 1999 was the worstoutbreak of fighting since the 1971 war. The conflict related to Indian attempts to dislodge some 700Pakistan-supported fighters occupying fortified positions along an 80-mile stretch of mountain ridgesoverlooking a key supply route on the Indian side of the LOC near Kargil. According to Indian sources, theintruders were mainly Pakistan and ethnic Afghan forces who crossed the border in early spring to seize highaltitude positions usually occupied by Indian troops in the summer. Pakistan claimed the forces were Kashmirimujahadeen, or Muslim freedom fighters. Although India used air and artillery barrages against the fortifiedpositions, these were often ineffective, and two Indian jets and a helicopter were downed early in theconflict. Much of the fighting came down to Indian infantry assaults on mountain peaks under near-Arcticconditions. Mounting casualties created domestic political and military pressure on the Indian government toorder strikes across the LOC to cut the supply lines of the infiltrators. Such suggestions althoughresisted by New Delhi fueled international concern over the danger of a widening war and the possible useof nuclear weapons.

Advertisement

By early June 1999, the United States and the other Group of Eight (G-8) countries had expressed concernover the destabilization of the LOC and urged India and Pakistan to seek a bilateral resolution of the tensesituation. In what was widely viewed as a major diplomatic victory for India, the Clinton Administration andmost international opinion refused to accept that such a largescale, well-supplied offensive could have beenplanned or executed without Pakistans support. India further claimed evidence that many of the fightersactually were Pakistan army enlisted men and officers. Then-Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif flew toWashington to confer with President Clinton on July 4. It was reported, in May 2002, that during this meetingPresident Clinton presented Sharif with evidence that (without Sharifs knowledge) the Pakistani militaryhad deployed nuclear-armed missiles to the border with India, a further indication of just how far theconflict had progressed.2 Following the meeting, the two leadersissued a joint statement in which they agreed that concrete steps will be taken for the restoration of theLOC, in accordance with the Simla Agreement. They further agreed that the dialogue begun in Lahore inFebruary provides the best forum for resolving all issues dividing India and Pakistan, including Kashmir.3Following Sharifs return to Islamabad, Indian and Pakistan military commanders met to discuss themodalities for disengagement of forces and the withdrawal of the infiltrators, which was largely completed byJuly 18.

Advertisement

Tensions between India and Pakistan remained extremely high following the Kargil conflict. In August 1999,Pakistan accused India of shooting down a naval aircraft over Pakistani territory, killing 16. India counteredthat it was shot down over Indian territory. The October 1999 military coup in Pakistan further souredbilateral relations because of Indias perception of Pakistan army involvement in the Kargil fighting. Indiaaccused Pakistan of being behind the December 1999 hijacking of an Indian Airlines plane on a flight betweenKathmandu and New Delhi. The plane was flown to Kandahar, Afghanistan, where it remained until the crisisended, on December 31, with the release of the passengers and crew in return for the release of three Muslimmilitants being held in Indian jails.

Advertisement

Throughout 2000, cross-border firing and shelling continued at high levels. India accused Pakistan ofsending a flood of militants into Kashmir and increasingly targeting isolated police posts and civilians.Pakistan also accused India of crossborder raids by Indian soldiers. According to Indian government sources,more than 5,000 militants, security forces, and civilians were killed in Jammu and Kashmir state in 1999-2000.The United States strongly urged India and Pakistan to create the proper climate for peace, respect the LOC,reject violence, and return to the Lahore peace process. The waning days of 2000 saw a reduction of tensionsas India announced in November that it was halting its military operations in Kashmir during the Muslim holymonth of Ramadan. In December, the Pakistan government announced that its forces deployed along the LOC inKashmir would observe maximum restraint and that some of its troops would be pulled back from the LOC. Indianarmy officials noted that clashes between Indian and Pakistani forces along the LOC had virtually stoppedsince the cease-fire began and that there had been a definite reduction of infiltration of militants fromPakistan.

Advertisement

In February 2001, Prime Minister Vajpayee extended the cease-fire for three months. The All PartiesHurriyat (Freedom) Conference (APHC) an alliance of 22 political and religious separatist groups in Indiacautiously welcomed the ceasefire offer if it represents a sincere step towards resolution of the Kashmirproblem. APHC leaders also sought permission from New Delhi to visit Pakistan in order to discuss theKashmir situation with Pakistani leaders and supporters of the Kashmiri separatist movement. Kashmirs mainmilitant groups, however, rejected the ceasefire as a fraud and continued to carry out attacks on militarypersonnel and government installations. As security forces conducted counter-operations, deaths of Kashmiricivilians, militants, and Indian security forces continued to rise. On May 23, 2001, the Indian governmentannounced that it was ending its 6-month unilateral cease-fire in Kashmir but that Prime Minister Atal BihariVajpayee would invite Pakistan military ruler General (now President) Pervez Musharraf for talks to pick upthe threads again...so that we can put in place a stable structure of cooperation and address all outstandingissues, including Jammu and Kashmir.

Advertisement

On July 14-16, 2001, Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee held talks with Pakistan President PervezMusharraf in Agra, India. Although widely anticipated as a possible breakthrough in India-Pakistan relations,the July summit failed to produce a joint communique, reportedly as a result of pressure by hardliners on bothsides. Major stumbling blocks were Indias refusal to acknowledge the centrality of Kashmir to futuretalks and Pakistans objection to references to cross-border terrorism.

The standoff between India and Pakistan over Kashmir has taken a new tone since the terrorist attacks onSeptember 11. Analysts in Washington have argued that two militant groups linked to al-Qaeda Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Muhammad have staged attacks in Kashmir and Delhi in order to provoke a majorstandoff between India and Pakistan and divert Pakistani military attention away from assisting U.S. effortsin the war on terrorism. On December 13, 2001, militants reportedly from these two groups attacked the Indianparliament building in Delhi, killing 14 and provoking the largest military buildup between India and Pakistanto date. After intense U.S. diplomatic pressure, Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf made a bold speech onJanuary 12, 2002 in which he promised to crack down on Islamic extremists. For five months, India adopted await-and-see attitude with troops mobilized along the border.

Advertisement

During the ensuing few months, efforts were made to allow both sides to withdraw their troops from thestandoff. Top Kashmiri leaders from both India and Pakistan met in Dubai on April 30, 2002. The thrust of thetalks reportedly centered on creating a congenial and peaceful atmosphere in order that India and Pakistancould negotiate and allow the Kashmiris to present their case. Sardar Abdul Qayyum Khan, the chairman of theNational Kashmir Committee of Pakistan, and Abdul Ghani Lone and Mirwaiz Omar Farooq, leaders of the AllParties Hurriyat Conference, attended the meeting.

The pro-Pakistan Kashmiri insurgent group Hizbul Mujahideen said it was willing to lay down arms if NewDelhi begins a genuine process of settlement and peace in Kashmir. In May 2002, in an article in theEnglish daily, Greater Kashmir, Deputy Supreme Commander of Hizbul Mujahideen, Moin-ul-Islam, stated,Once India takes an initiative with good intentions, she will find us ten steps ahead of her one step. Wewill at once give up guns and observe real ceasefire so that [a] solutionfinding path receives headway.4(Subsequently, the authenticity of this offer was reportedly rejected by official Hizbul sources.) Hizbulshead, Syed Salahuddin, went on to expel its chief operations commander, Abdul Majid Dar, and two of hisfollowers. Dar was the Hizbul leader who had offered a cease fire in 2000 that had held out hope for peacefulnegotiations in the valley. Some reports suggested that Dar was considering running for office in theSeptember elections to the Kashmir assembly. The fact that Dar and other Kashmiri separatists are evenconsidering an election run suggests that there is growing exhaustion with waging a brutal insurgency that hastaken its toll on both the Indian army and the insurgents. Participating in the electoral process may be oneway to attain some of the goals that the insurgent groups have been seeking.

Advertisement

The move to seek other avenues may also be coming from the concern that Pakistan, as shown by its policyreversal towards the Taliban, might reduce support to the Kashmiri mujahedeen. In that case having analternative makes tactical sense. Some analysts also argue that infiltration will become more difficult asIndia gets better surveillance equipment from the United Statesparticularly sensors and systems for bordermanagement. In fact, some Indian sources believe that intelligence and technology sharing between the UnitedStates and India may be the best way to monitor infiltration along the LOC.5It has been reported that U.S., Russian, and Indian satellites are now monitoring both militant camps as wellas troop movements along the border.

Advertisement

The military standoff between the two countries has raised the fear of a nuclear war, and both domestic andinternational factors have made it difficult for either side to back down. The scope for miscalculation alsopersists. President Musharraf faces domestic pressure from the main stream political parties that he alienatedby his decision to hold a referendum in April 2002. He also faces criticism from hardliners within themilitary who first opposed the decision to stop supporting the Taliban and are now against compromising withIndia.

The world community has not supported Pakistan to the extent it may have expected in the current conflict.The leaders of several western countries have called upon Pakistan to halt cross border infiltration bymilitant Kashmiris. Western leaders have also been concerned because the Pakistani government has not declareda no first use policy on nuclear weapons. Pakistans reluctance to do so comes from it conventionalweapons inferiority vis a vis India. The international community is concerned, however, that nuclear weaponscould be used as the first, and not the last, resort in a major conflict. Initial utterances by Pakistaniofficials on the lack of a no first use policy alarmed the international community. British Foreign SecretaryJack Straw said that such a policy could not be tolerated, which led President Musharraf to subsequently saythat a nuclear war would be unthinkable and should not be allowed to happen.

Advertisement

At the domestic level, President Musharraf is facing criticism about his April 30th referendum that wasboycotted by the major political parties in the country. Jihadi groups within the country are angry with thepresident for attempting to halt infiltration into Kashmir and for removing support for the Taliban.6Groups within the military, so called Islamic hardliners, also reportedly are angry with Musharraf forbecoming a lackey of the West and for giving up both of Pakistans Jihadi strategiesin Afghanistanand Kashmir.

Successive Pakistani governments have viewed reclaiming Kashmir as vital to the countrys nationalinterest and identity. Making concessions on Kashmir, without a quid pro quo about the disputed status of thestate, would be seen as bowing to Indian and international pressure. In discussions with India, however,Pakistan will be under pressure to take a different approach from the past one of using the support ofmilitants and the declaration that Kashmir is the core issue in India-Pakistan relations.

Advertisement

President Musharraf stated that the only way to solve the Kashmir problem is, through flexibility fromstated positions on both sides. Pakistani observers view this as significant since the militaryestablishment has traditionally been very rigid on its irredentist stand on Kashmir.7Such flexibility, it has been argued, will be required to lower tensions between the two countries and helpinitiate a series of confidence building measures between them.

On the Indian side domestic constraints come from the Indian perception of national identity, the concernwith national unity, and, more immediately, from the declining political fortunes of the Bharatiya JanataParty (BJP). Indias belief is that Kashmir represents an integral part of its secular identity, and thatlosing Kashmir would suggest that the Indian state cannot function as a multi-ethnic, multi-religious entity.Less articulated is the fear that if one ethnic grouping breaks away from India, others might follow suit.India has faced separatist movements in both the North- East and the South. Finally, the BJP has facedwidespread criticism at home and abroad for its poor handling of the sectarian violence in Gujarat that led tothe deaths of over 800 people.

Advertisement

At the international level, the Indian government is attempting a delicate diplomatic strategy of askingthe international community to put pressure on Pakistan while simultaneously keeping other nations frominternationalizing what New Delhi views as a bilateral dispute with Islamabad. The constraints on both theIndians and the Pakistanis help explain what attempts may work in managing the relationship between the tworivals and in helping contain the situation in Kashmir.

On the Indian side there was some discussion of waging a preemptive limited war in Kashmir. The goal was towipe out the militant training camps in Azad Kashmir without provoking a broad conflict with Pakistan. Thereported plan was that the Indian Air Force would launch precision strikes on the camps in the same way as theUnited States Air Force had on al-Qaeda locations in Afghanistan. This was to be followed by an attack byIndian special forces on these sites. Heavy casualties were expected.

Advertisement

The plan rested on the assumption that Pakistan was willing to limit the conflict and would not use nuclearweapons. The latter view came from the belief that Pakistans nuclear weapons had been secured by the UnitedStates and, therefore, would not be used in a conflict.8 Implementingthe plan would have been difficult. India lacks the precision guided munition arsenal to carry out suchstrikes on 60-70 camps in Azad Kashmir. It would also run into fierce opposition on the Pakistani side of theborder. More difficult to contain, however, would have been the outbreak of conflict in other border areas.Worse, if Indian reports are to be believed, Pakistan may have tactical nuclear weapons and, if deployed inKashmir, a military commander would have no incentive to exercise restraint if his positions were beingoverrun by Indian forces.

Advertisement

In May-June 2002, the efforts of Deputy Secretary of State Armitage and Defense Secretary Rumsfeld helpedreduce tensions in the region. India has agreed to allow overflights by commercial aircraft if Pakistanreciprocates. The Indian government has recalled the five naval vessels that were patrolling close toPakistani waters and is likely to name a new ambassador to Pakistan. President Musharraf has adopted a waitand see approach and says he will be satisfied when India reduces its force levels along the border.

Maintaining long-term stability and security in the area, however, requires that both countries worktogether, but at the moment their agendas diverge. The Indian government has repeated its earlier offer ofjoint patrols of the border. The Indian logic is that the militaries of both countries know the border welland they can collaborate effectively to halt infiltration. Pakistan, while not rejecting the proposal out ofhand, has expressed doubts about its feasibility. It has argued that given the current state of tension anddistrust between the two armed forces it would be difficult to operationalize such patrolling. The otherproblem is that by agreeing to joint patrols Pakistani officials fear that this would be a de factoendorsement of the LOC as the international boundary between the two countries. Pakistan reportedly wouldprefer to have an international force monitoring the LOC, since such force would be easier to implement and itwould help internationalize the Kashmir issue.

Advertisement

India is unlikely, at least officially, to welcome a multinational force because that it is committed bythe 1972 Simla Agreement to bilaterally resolve all disputes with Pakistan. It is also concerned that amultinational force would put pressure on India to resolve the Kashmir dispute to Pakistans advantage. Onereport has also suggested that India might allow U.S. special forces into Indian Kashmir ostensibly to huntfor al-Qaeda forces but actually to monitor the border.9 Other reportsindicate that the United States has agreed to give India sensors to monitor the border.

When coupled with the war on terror and U.S. relations with India and Pakistan, the Kashmir issue becomescomplicated and difficult to address through foreign and security policy. The anti-terror campaign and huntfor al-Qaeda in the region would be hampered considerably if the Kashmir conflict were to escalate to all-outwar. The threat that such a war would further escalate to include nuclear weapons also presents seriouschallenges to U.S. nonproliferation efforts. Defusing the current crisis and establishing some degree ofstability in Kashmir is, therefore, important to U.S. long-term interests.

Advertisement

Until the September 11 attacks on the U.S., however, in terms of U.S. global strategy, South Asia tended tobe of lower interest to the United States than the Middle East or East Asia. U.S. forces in Asia areconcentrated in South Korea and Japan with a focus on potential hot spots along the Korean Demilitarized Zoneand the Taiwan Straits. Pakistan became a front-line state for the United States only because of the campaignin Afghanistan. In the absence of the war on terrorism, there would be few strategic resources for the UnitedStates in the region, nor are there strong historical, cultural, or ethnic ties to it. Should the war onterror move away from South Asia, American interest in the region could wane. Furthermore, despite marketreforms by both India and Pakistan, the volume of U.S. trade with and investments in these countries remainsrelatively low. In other geopolitical contexts, however, such as U.S. relations with China, the focus on Indiaand Pakistan could intensify, depending on circumstances.

Advertisement

The ability of the U.S. government to generate the domestic political support necessary to intervene inSouth Asian affairs or for India and Pakistan to accede to U.S. influence tends to be greatest in crisissituations such as the one that currently exists. Over the longer term, however, the United States couldfind it difficult to maintain the type of long-term political and military commitment to South Asia that ithas maintained for other regions, such as East Asia or the Middle East. Currently, the policy options for theUnited States to deal with the Kashmir conflict seem to be to reduce tensions between India and Pakistan, toencourage an ongoing dialogue and confidence building measures between the two countries, and to work toreduce terrorism in the region and worldwide.

Advertisement

Since much of the current tension has arisen because of alleged incursions from Pakistan across the LOC, animportant step in reducing tensions might involve some type of monitoring of the LOC in Kashmir. A systemwould be required that would allow India to present proof of reported incursions but also enable Pakistan toreject any false claims of infiltrations. Airborne or satellite surveillance would be nonintrusive and couldhelp both countries make their cases. Another possibility would be to expand the United Nations presence inSouth Asia to include monitoring the LOC. Currently, India opposes an expanded UN role, as noted above.

Another source of tension is the short reaction time to a possible a nuclear attack by either country whether intentional or accidental. The concern is that neither side may have sufficient controls in place toprevent either an accidental launch or a nuclear strike by rogue forces. A reduction of nuclear tensionsrequires that both countries have the technology in place that will allow them to have better control overtheir nuclear weapons and mechanisms and facilities in place to prevent accidental launches or theft. In thepast, Western nuclear powers have been reluctant to provide these technologies because it made nuclear weaponssafer to deploy. Now that each side appears to be operationalizing its nuclear weapons, more cooperation maybecome necessary. Pakistan already has a nuclear command structure, while India is reportedly moving towardestablishing one.10

Advertisement

Encouraging an on-going dialogue and confidence building measures between the two countries would includeseveral specific projects, many of them non-military. For example, one could be discussions on easing travelrestrictions across the LOC, particularly for those with cross-border familial ties. A second would be thesharing of river waters. The Indus Waters Treaty guarantees Pakistan a share of river water flowing fromIndia. During the military standoff some analysts in India argued that the country should shut off the watersupply to Pakistan as a way of coercing it to halt cross-border terrorism. The time may have come to discussthe latter part of the Indus Waters Treaty that deals with the development of riparian resources. For the twocountries, harvesting river resources cooperatively could prove mutually beneficial. Pakistans water supplywould be further guaranteed, and India, like Pakistan, could benefit from developing resources in the heart ofits agricultural region.

Advertisement

With regard to the anti-terror campaign in the region, this is discussed in other CRS reports and issuebriefs.11 It is worth noting here, however, that in the solution tothe Kashmir conflict, a haven for Islamic extremists organizations not be created. As veteran South Asiaobserver Selig Harrison has argued, there is the real danger that an independent Kashmir, given the Jihadinature of some of the insurgent groups, could end up as another permanent sanctuary for Islamic extremistterrorist operations.12

1 See also CRS Report 98-570, India-Pakistan Nuclear Tests and U.S.Response and CRS Report RL30623, Nuclear Weapons and Ballistic Missile Proliferation in India andPakistan: Issues for Congress.

Advertisement

2 Sipress, Alan and Thomas E. Ricks, Report: India, Pakistan were nearnuclear war, The Washington Post, May 15, 2002.

3 Text: Clinton, Sharif joint statement on Kashmir conflict, USISWashington File, July 6, 1999.

4 Hizbul offers ceasefire, flaysHurriyat, The Indian Express, May 3, 2002.

5 C. Raja Mohan, Indias Focus on Sharing Intelligence with U.S., TheHindu (New Delhi), June 6, 2002.

6 Jason Burke, Betrayal ofConfused Jihadis, The Observer, June 9, 2002.

7 Imtiaz Alam, Success of anUnavoidable Retreat, The News International, June 10, 2002.

8 Ahmad Faruqui, India Losing the Initiative, Asia Times,June 5, 2002.

9 Siddharth Varadarajan, Rumsfeld hasSpecial Forces Offer for India, The Times of India, June 12, 2002.

Advertisement

10 See CRS Report RS21237, Indian and Pakistani Nuclear Weapons Status,by Sharon Squassoni.

11 See CRS Issue Brief IB94041, Pakistan-U.S. Relations, and CRSIssue Brief IB93097, India-U.S. Relations.

12 Selig S. Harrison, Indias Bottom Line, The Washington Post,June 11, 2002.