This excerpt is from Chapter X and is about the historic Northern Province elections that were held in Jaffna in September 2013 for the first time in decades and just 4 years after the end of the devastating civil war against the separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), during which more than 120,000 people were killed. The elections were contested by former Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa's then ruling coalition, but won resoundingly by the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), whose candidate Justice CV Wigneswaran was named Chief Minister. The author spoke to a vast cross-section of Sri Lankan Jaffna Tamils, first at the TNA's last election rally before the polls, in bustling markets, in a village rebuilt by the Sri Lankan army and finally, at a polling booth on election day. Some Tamils voted for Rajapaksa, many voted for the TNA. Everyone wanted a better future for Sri Lankan Tamils, but only within a united Sri Lanka. There was and is no talk of separatism in North and East Sri Lanka any more.

Gurunagar, a small maze of narrow alleys wore a festive atmosphere. There were yellow- and-orange buntings of the TNA everywhere. I wondered about the TNA’s party symbol—a house—which I had already seen fluttering all over Jaffna. What did it stand for?

A ‘homeland’, all over again?

Or did it mean that Tamil electoral politics—through these elections—had finally come home, so to speak, to roost? To a new maturity and willingness to tackle a feeling of alienation and deprivation over decades of both Tamil and Sinhalese chauvinism, through a democratic process? Towards the end of my trip, I was to get a mystical, but no less baffling explanation.

At the Kalai Arangam, the crowd was so large that the rally had been shifted outdoors. There were rows of people sitting on plastic chairs facing a skirted podium, many elderly people were in wheelchairs, patiently awaiting the arrival of the TNA brass. Those who couldn’t find a chair stood at the back. Some youngsters sat on the veranda wall of the community auditorium building, dangling their legs and testing the plastic whistles that they had slung around their necks. As many as 2,000 people had gathered there that evening.

Unlike most election rallies in India, this one started on the dot of time. Senior leaders, the distinguished, white-haired V. Sampandan and the tall, stately chief minister-designate C.V. Wigneswaran had arrived.

Sampandan lights a lamp and then the two leaders are smothered with garlands. Whistles and cheers greet the two men as they sit down with other senior leaders. A very shrill woman takes to the mike, and after introducing the leaders on stage, launches into a rapid-fire speech which goes entirely above my head. Suddenly, there is a two-minute silence. Even some wheelchair-ridden elderly struggle to stand up.

I am standing in the crowd behind the last row of chairs (though I was not surprised when several people offered me theirs) and I look questioningly at a couple who happen to be next to me, with whom I had earlier exchanged a few words in English. The husband translates the announcement as ‘for all those who died’. His wife goes a step further. She whispers into my ear: ‘For the LTTE, but they can’t say that loudly …’

Having spoken to Wigneswaran just some months ago, I don’t quite believe her but am surprised to see that the LTTE still seems on the minds of some people here. While the leaders speak, a gentle breeze blows from the sea and I can see children on swings in the playground nearby.

I drift away down a narrow Gurunagar lane, which is known as ‘widows’ colony’, as the lady at the rally had told me. An elderly grandmother is out strolling slowly with her small grandson. I ask her why she is not at the rally. ‘I don’t have to attend since I will vote for the TNA anyway,’ she says. ‘Rajapaksa has not done much for us war widows, but I have to vote for someone, I suppose. Peace is good, but much, much more needs to be done for us.’ Outside the Jaffna Teaching Hospital, the main street is bustling with activity, and finding a place to park has become almost as hard here as in Colombo. There are ticket-happy policemen all over the place, busy scribbling tickets at a cluster of motorbikes parked in the middle of the street on every available inch of a traffic island. At a pharmacy, I chat with a forty-year-old doctor. She is happy to talk, but does not want to be taped or named.

‘No matter what the TNA does, I think Rajapaksa’s alliance will win,’she says. ‘They have more money, more resources and lots of people working for them. But I will vote for the TNA. I believe they will work for us.’

But isn’t Justice Wigneswaran essentially a ‘Colombo man’? One disconnected to realities here in faraway Jaffna?

Advertisement

‘It is precisely because he is that, I will vote for him,’ she says, walking out of the shop slowly with me. ‘It is only someone with roots in Colombo who could persuade the Central government there to give us more. And as a Tamil himself, at least he will be able to understand our problems better than someone with absolutely no roots here,’ she says. Then she sighs and says something intriguing. ‘The war may be over, but complete peace is yet to return.’

I ask her to explain what she means. After all, there is development at breathtaking speed all around us.

Advertisement

‘Well, there are problems in the Wanni, for instance,’ she says vaguely, ‘I hear that there are lot of people still missing there. We want those questions answered.’

I walk down the shopping street, marvelling again at the baskets of sienna-coloured dried shrimp and gigantic katta, dangling from hooks on the rafters of small shops. I know that both are famed delicacies of Jaffna. Thennekoon, my driver, asks me almost apologetically, if it is okay for us to stop here on our last day to take some back to Colombo too. One shop owner, Selvaraja, is a jovial man, a fisherman himself, who insists on giving me a free sample when he hears I am from India.

Selvaraja is enthusiastic about the elections but is a Rajapaksa voter. ‘Come what may, I will vote the bulath kole (betel leaf),’ he says, referring to the symbol used by Rajapaksa’s coalition and using the Sinhala and not the Tamil word (vettal). I ask him why. ‘Business has picked up again, no?’ he says with a smile, handing over the busy counter to his assistant to step aside to talk to me. ‘Also, Rajapaksa is taking big action against your fishing boats …’ he trails off with a sheepish grin.

He is referring to the gigantic Indian trawlers that have been relentlessly out-fishing small Jaffna fishermen by illegally trawling in Sri Lankan waters. Still, I am surprised at his glee over the frequent arrests made by the Sri Lankan navy of Indian fishermen, who, are mostly from Tamil Nadu, the ‘blood brothers’ across the Palk Straits. An older man who has been buying fish, steps forward. ‘Excuse me, my name is Sivaraja,’ he says. The fifty-six-year-old engineer is keen to add an opinion, which I accept gratefully. ‘There were elections here in 1987, when your country under Rajiv Gandhi had first created this Northern Provincial Council,’ he says. ‘I had voted even then. But since then, indeed for the last forty years, we have seen only problems. This time, I will vote for the TNA and it is definitely going to win. And we hope that they will bring about some change to our mood—for the last half-century, we have had to deal with mindsets. Both the Sinhalese and we Tamils have a mindset that has not changed.’

So what is this mindset, could he elaborate? What has not changed and what has?

‘See, first of all, Amma, I want to assure you that there is absolutely no problem of living in a united Sri Lanka. Of course, we must be a united country,’ Sivaraja says, neatly spreading his handkerchief on a bench under a shady tree, as we sit down on it. ‘But since independence, the Colombo government has not divided resources equally. They have not given us our share. I will say this much, under Rajapaksa this has somewhat changed, for the last four years he has been investing a lot here. But before that, we neither got the funds nor did we get the jobs.’

I remark on the similarity between Sri Lanka and the rest of South Asia, that every country has at least one region that is neglected and underdeveloped.

‘I agree, all politicians are the same in all countries,’ he says. ‘Even all this development,’ he waves his hand around the bustling market, ‘ultimately, it comes from our tax money, not from their pockets. They get loans off our tax money for all this. So, this is something due to us anyway.’

But given the long civil war, surely no government—no matter how well meaning—could have come in here and started developing the Northern Province much earlier? To that extent, must not the Tamils of Sri Lanka too take some part of the blame?

‘Yes, certainly,’ Sivaraja concurs. ‘This may sound surprising to you, coming from outside. But none of us wanted this war. If you asked any of us during the war, whether we wanted it, you would have found most of us saying no. But that we wanted a “solution”, that is all we wanted. That is all we want. We are a minority, but they must start listening to us.’

‘Let People Say What They Want to:

We Will Vote for the Army’

For all its lagoons and backwaters, Jaffna is essentially a flat, fertile land. The hot noon sun is now beating down fiercely and yet, the green cover of Palali—which just four years ago was an apocalyptic landscape—has already grown enough to provide welcome shade to vehicles. After ten minutes of driving, the aide’s car turns onto a dirt track. It leads to a row of villages, scattered between fields and coconut groves.

Fortunately, the aide doesn’t seem to want to show me a ‘model house’ or ‘model family’. So I step tentatively into a side alley of my choice and he follows me. Most people are indoors in the afternoon. I spot a woman hanging out washing. She sees me and the aide and greets him. She readily agrees to chat with me, ushering us inside, but looks surprised when the aide indicates that he is going back to his car on the main road down the lane. ‘Please take your time, ma’am,’ he says to me and disappears.

I find myself half-wishing that he had stayed. He is a Sinhalese boy, but can speak excellent Tamil. I decide to brave it out with my tape recorder and my embarrassing language and follow the lady into a fenced-off compound.

There are two houses here. One is old and battered, with a thatched roof. It looks abandoned. Just behind it, is a newly painted cement house, with a wide, thatched veranda running around it. Here, an elderly lady is playing a game of ‘five stones’ with a small child. Near her, a white-haired man dozes on a pai (strawmat). Behind the house is a clearing, stretching towards some lush fields.

There is a robust breeze blowing from the sea. It is still and peaceful. The younger woman gives me a brilliant smile and introduces herself.

‘My name is Kanaga Swamy (name changed to protect the interviewee), I am thirty years old,’ she says. ‘My husband works as a coolie on a construction site. I too work. I am good at making snacks like muruku, so I make those and sell them in the town.’ I ask her how she feels, as a Tamil, living in such close proximity to the army.

Her face lights up. ‘The army? For us, this is the best place to live,’ she says. ‘Our baby (she points to the round-eyed little girl who is looking at me and my tape recorder with great curiosity) Alankrutha (name changed) would have died, if it were not for these people.’

Kanaga tells me that two years ago when Alankrutha was a year old, she had fallen sick. The family took the child to the Jaffna Teaching Hospital where they were told that the baby would need heart surgery. ‘We did not have the means,’ she said softly. ‘And were desperate and wondering what to do. Somebody must have told them but just a day later, one boy from the army came to our house—this old one here in front,’ she says, pointing to the more dilapidated structure. ‘He said the commander (I assume she meant Hathurasinghe) had heard of our problem through the other people and wanted to come home. They came with a doctor, who examined the child. The next thing we knew, we were in an aeroplane, being taken to Colombo. There in the big hospital, they operated her. Since then she is perfectly okay and has never had a problem. Even today, the officers come to visit frequently just to see how she is faring.’

Her fifty-nine-year-old mother Laxmi (name changed) prods her daughter from behind, indicating that she too wants to say something to me.

She points to the sleeping man. That is her brother, Ilaiyaraja (name changed). He is two years older than her. He had two sons, both of whom were forcibly taken away by the LTTE, she says. One was killed and they received the body. On the other, there has never been any news.

‘We are originally from Kandavaram in the Wanni,’ Laxmi continues. ‘There, we were very poor. We had no livelihood and didn’t know what would happen to us. Even I had two sons, older to Kanaga. One was killed in the fighting, and the other was shot trying to run away from the LTTE.’ Her voice has risen slightly, and it wakes the older man asleep on the mat.

While we are speaking, Ilaiyaraja takes a sip of water from a small earthen kooja nearby and shuffles up to us. He too seems anxious to add something. ‘The LTTE,’ he says forcibly, holding up forefinger to my tape recorder, almost as though he hopes it will record the finger underlining his anguish too, ‘was only involved in violence, absolutely nothing else. Our life in the Wanni was miserable. They kept taking our children away. There was no food, no power, absolutely nothing in our lives except blood. Blood, blood…’ as he picks himself up laboriously to disappear into the house, his voice trails off.

I try to ease the sombre mood by bringing up the elections. So whom are they going to vote for? The house, or the betel leaf? ‘The army, the commander,’ say mother and daughter almost at the same time, with a big smile and nod, when I confirm that they know that means they would be voting the betel leaf, the Rajapaksa coalition.

‘The army to us is everything. They have given us livelihoods. Even this new house,’ says Kanaga pointing to the cement structure on whose veranda we are sitting. ‘They give us food, they routinely come to see if we are okay. When we fled here, we had nothing, we built that older house over there. Over the years, it collapsed partly. Yet we continued to live in it. After Alankrutha’s surgery, the commander asked me what I could do, if I had any skills. I told him that I could make good snacks. So he found me a job too.’ But surely they know that most of their compatriots in Jaffna are going to be voting for the TNA? Why don’t they want to do so as well? After all, only Tamils could understand what other Tamils want?

Kanaga confirms that many TNA election campaigners have visited them here in these villages at Achuveli, near the Palali base. But she shakes her head vigorously.

‘See, Akka, I can tell you this. People do come to visit us, but they know very well that we get all our support from the army. It is the army that has taken care of our every need. They have given us cattle, goats, houses and even built proper toilets for us. That is why, you won’t find anybody in this entire area (where,I learn later from the aide, a total of 15,000 houses have been built so far by the army) who will not support the army. When these ‘veedu’ symbol people (TNA, whose symbol is a veedu, Tamil for house) come, we listen politely and say yes, yes. But they know and we know that we will only vote for the vettale (Tamil for betel leaf). We have spent our lives in fear. But being so close to the camp now, we don’t know what fear is.’

Are people like Kanaga ever threatened? By those who don’t want them to vote for the ruling party?

She shakes her head firmly. ‘No, nobody would dare to threaten us, given how close we are to the army. Initially, whenever we went to town, people who got to know we were from this area would give us some strange looks. But I think, over the years, they know well that if anybody has done anything for us poor people here, it is the army.’

A few houses down, I visit thirty-three-year-old Malini Kamaleswaran (name changed). She has four children but they are all at school right now, so she has time to chat. When I mention the TNA, she snorts loudly.

‘The house? They have never done anything for us. They are just bullies. They only come when there are elections. I don’t mind who hears your tape, Akka, but I will say this. The war is over. We want to live with these Sinhalese people together in peace. It is only because of the army that we have anything at all. See that shack over there? That is where we lived—first my parents and more recently my husband and I—for the past thirty years. It is the 500 Brigade that built a house for us. Why would we vote for anyone who has done nothing for us? Are we mad?’

While we are talking, a frail and elderly man in a sarong has limped up. He is Malini’s neighbour, sixty-five-year-old Kuppuswamy (name changed). Seeing that I was about to leave, he gestures that he too has something to say.

‘Amma, I have nobody, I am alone. I once had a brother. But you cannot imagine the kind of days we have seen, my brother and I. We used to go and sleep in the jungle after dinner, just for fear of being taken away by the LTTE,’ he says. ‘But life is cruel. One night in the jungle, a viper bit my brother and he died there. Since then, I have lived alone, in grief and fear. All this—my small house over there—was given to us by the army. I can only pray,’—and he puts together his weathered, trembling hands together—‘really pray, that Rajapaksa wins this election. We badly need this—samadhanam—peace to last.’

Polling Day, Clueless Police and Young Voters

By now, even Thennekoon was, as drivers always are, in the journalistic swing of things.

He was up well before I was, and had already taken a walk around the area near Asirvatham Lane where Green Grass is located. Whenever he returned from such outings, he came back with new local contacts, new friends. This time, and as I gulped down my breakfast, he informed me that voting was already going briskly at 7 a.m. when the first booth had opened and that he now knew where the best katta was to be had. So if I didn’t mind, we would halt there on the way out of Jaffna the next day.

We set out to cruise the town and stop at any polling booths with large crowds.

I did not need to go far.

At the Chundikuli junction, streaming into St John’s school, was a long line of voters. It was still quite early, the morning air was pleasant and filled with the fragrance of breakfast curry. Being a holiday, the voters too seemed relaxed and quite excited.

Advertisement

The sight filled me with a rush of hope for this new country: so many aspirations, so many dreams. But whenever I had that rush, it was always clouded over almost immediately by anxiety, an awareness of just how fragile those hopes had been in the past. I brushed my thoughts aside briskly, told myself not to be sentimental and strode towards the gate of the school.

The cops at the gate were clueless and very rude. They were the first—and last—impolite Sri Lankans I have ever met. They spoke no Tamil, no English, only Sinhala, which is fine, except that they were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

I showed them a plethora of passes and permits I had for covering the elections, and yet, they snapped at me and tried to shoo me away. I stood my ground, pointing very slowly at the Sinhalese letters on my press card, which pretty much said what all press cards say. That I am to be allowed to go wherever press is allowed.

Finally, they had to relent but insisted rather absurdly, that I leave my cellphone behind, though all voters were carrying them along and local photographers were going inside with much heavier and obviously professional equipment. I relented only because I am, after all, a foreigner and further, I was in an upbeat mood and wasn’t going to let a couple of silly “control freaks” get me down.

Of course, I had numbers in my cellphone and it would have taken a single call to an authority in the foreign ministry in Colombo to sort out the issue. But I didn’t do that, curious as I was to see just how ill-fitting southern police are in the north.

Inside, the polling booth was neat and orderly. All voters carried a national identity card, a passport or a driving licence. One polling officer told me that 300 people had already voted at that booth between 7 a.m. and 10 a.m.

Since the policemen were following me around and breathing down my neck as though I were the immediate heir to the last slain leader of the LTTE, I decided to not talk to voters here but on the main road, just outside the main gate to the school and annoyingly for the police, well within their sight.

The issue of whether control over the Jaffna police forces must be handed over to the provincial council or not, as the TNA was demanding and as envisaged by the 13th Amendment, is not something on which I have an inflexible position.

But one thing I will say: the sooner the ongoing training of local Tamil boys and girls for senior and junior positions in the Jaffna Police Force—no matter who administers it—is completed, the better.

Just outside the school, while the cops at the gate glared at me with impotent surliness, young documentary film-maker Murugan (name changed) born in 1988—just a few years after the war broke out in full force—had stopped for an ice cream with his dad. He chatted easily with me. ‘My entire life was spent in the war,’ he said. ‘Yet I say, there is no need for separation, but we want a political solution first and only then, all this development.’ He also handed me his card and, with eager business canny, told me to contact him first, if I ever needed any filming in the peninsula.

His father Kunanayagan (name changed) answered with the greater eloquence of a sixty-four-year-old. Both of them had voted for the TNA but Kunanayagan’s philosophical response said it all. And almost, but not quite, answered the question on my mind at the TNA election rally a day before, as to what the ‘house’ symbol of the TNA could possibly stand for.

‘We don’t mean that we don’t appreciate all this development,’ he said softly. ‘But, madam, we Tamils, after all, are still living in a rented house, no?’

Advertisement

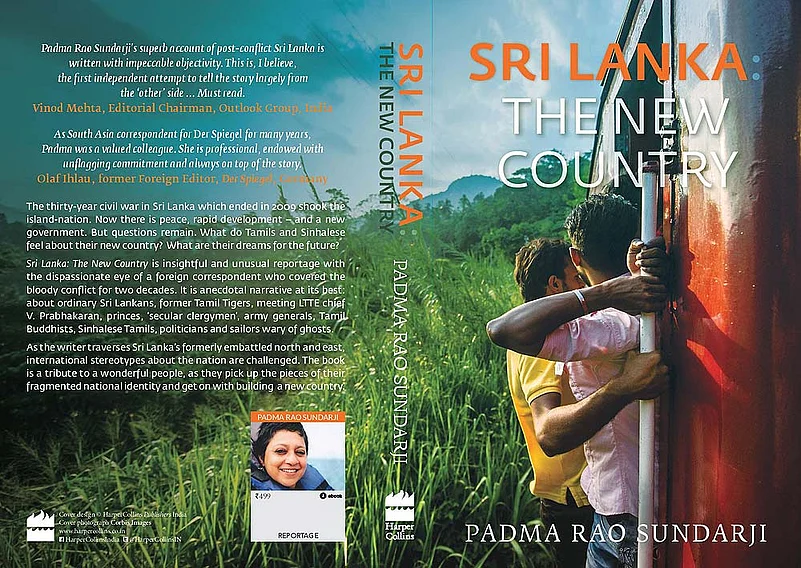

(The author is the former chief of South Asia bureau of German magazine Der Spiegel. In the mid-1990s and since the day Outlook launched, she was its New York correspondent. She dedicates this excerpt to the late Vinod Mehta, who read the manuscript of “Sri Lanka: The New Country” just before it went to print. His comment graces the back cover of the book).