Amid the Centre’s attack on the judiciary, it is instructive to remember what Union Minister of Law and Justice Kiren Rijiju, spearheading the ongoing campaign, had said in the Lok Sabha a few months ago. Asserting that it is unfair to blame the judiciary for pending cases, he said on July 26, “Judges work hard ... there are judges who have settled hundreds of cases in a day ... they work from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m.” Rijiju emphasised that the reason for pendency is “something else”.

The next month, when Rajya Sabha MP Kapil Sibal expressed his displeasure over some recent Supreme Court judgments, Rijiju quickly reprimanded him, saying, “It is sad that prominent leaders and parties are criticising constitutional authorities and agencies. These agencies are absolutely autonomous.”

Advertisement

Two months down the line, however, the tone and tenor of the law minister changed. Making a volte-face, Rijiju linked the pending cases to the “procedure of the appointment of judges”. What began as criticism of the collegium system has now turned into an unsavoury diatribe, encompassing several issues ranging from vacations to bail petitions. Apparently, the government is now finding fault with the entire judicial system.

What triggered the reaction? Outlook spoke to several Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leaders, who hinted that it is part of a larger scheme, maybe an attempt to introduce a fresh version of the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) Act. A five-member Constitution Bench of the top court headed by Justice J.S. Khehar had on October 17, 2015 held the NJAC as “unconstitutional and void”. It is also surmised that another seed may lie in the long tenure of Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, who took oath as the Chief Justice of India (CJI) on November 9. During his two-year tenure, he will preside over the appointment of nearly 20 of the 33 Supreme Court judges and a large number of high court judges. The judges over whose appointment he would have the final say will decide the actions by the executive and the legislature for several years to come.

Advertisement

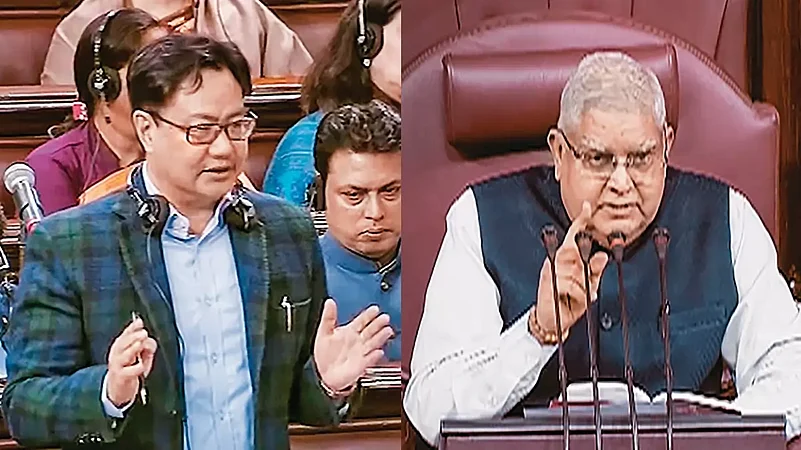

Such is the exasperation that no less than Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar entered the fray. Dhankhar told the Rajya Sabha in December that the Supreme Court’s move to scrap the NJAC Act was a “severe compromise of parliamentary sovereignty”. There was “no parallel to such a development in democratic history where a duly legitimised constitutional prescription has been judicially undone,” said Dhankhar.

Truth be told, the country’s vice president attacking the top court in the Rajya Sabha was unprecedented. As a senior advocate, Dhankhar had appeared before the same court on several instances. “Dhankhar was very composed and charming when he appeared before us. I was shocked to hear him speaking against us in such words,” a retired Supreme Court judge tells Outlook.

The judicial fraternity sees a larger design behind the government’s statements. Former Supreme Court judge Deepak Gupta finds it “a concerted and systematic attack by the government to undermine the judiciary”. Another former judge of the top court Justice Madan Lokur termed it “most unfortunate”. “What makes it worse is that it appears to be concerted,” Lokur tells Outlook.

Curiously, some Opposition leaders have also joined in. After Rijiju questioned the court vacations, Congress MP Vivek Tankha said, “It is the sentiment of the nation and everybody is feeling the need for reform… There is nothing wrong if the law minister makes the suggestion.”

Advertisement

But the CJI knows the authority he wields. Ignoring the comments, Chandrachud declared that there would be no vacation bench during the winter break. His fellow judges have not minced words either. Calling the Supreme Court the “most transparent institution”, a bench of justices M.R. Shah and C.T. Ravikumar recently said that the collegium system cannot be derailed because of the statements of “some busybody”. During another hearing, Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul almost told Attorney General R. Venkataramani to shut his mouth, saying, “I have ignored all press reports, but this has come from somebody high enough.”

Advertisement

Since the judgments of the Supreme Court and the high courts significantly impact democracy and the government’s functioning, it is perhaps natural for the executive to seek favourable judgments. Judges are also voters and follow certain beliefs and ideologies. They may face a dilemma while deciding cases that are not only about law, or its interpretation, but also about various aspects of life and democracy. “Judges also have their own biases. Judges should first identify their own biases. Why should we get into philosophies? If a judge is into the environment, they may give a judgment in an environmental case that stretches the boundary. That is where the tussle starts,” says Gupta.

Advertisement

But the nucleus of the present tussle seems to be the collegium system. For decades, the appointments were largely led by the executive. Indira Gandhi even superseded three senior most judges to bring in her own man. The Supreme Court devised the collegium system in the early 1990s and assumed the primacy over the appointment of judges.

In 2000, the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government appointed the Justice M.N. Venkatachaliah Commission to review the working of the Constitution. The commission recommended the setting up of a National Judicial Appointments Commission, consisting of the CJI and two senior most judges of the apex court, the Union law minister and an eminent public personality, to be chosen by the President of India in consultation with the CJI. In 2013, the UPA government brought a bill to establish a Judicial Appointments Commission. The next year, the NDA government introduced the NJAC Bill, which was unanimously passed by both the upper and the lower houses. However, the top court struck down the NJAC and upheld the collegium system in 2015.

Advertisement

Several judges admit that the collegium system has its deficiencies, but they also point out that the government’s accusation is unfair. “To say that the collegium system has led to the excessive dominance of the judiciary over the appointment of judges is a bit of a joke,” Lokur tells Outlook.

But the collegium faces another criticism related to its non-transparent proceedings. In 2021, the collegium’s decision to transfer the Madras High Court Chief Justice Sanjib Banerjee to the Meghalaya High Court had led to a controversy. Several lawyers of the Madras High Court wrote to the CJI and the collegium members expressing their displeasure over the transfer of a chief justice of a large high court to a fairly smaller one. It was the rerun of a similar situation in 2019 when Madras High Court Chief Justice Vijaya Kamlesh Tahilramani was transferred to the Meghalaya High Court. She sent a representation to the collegium headed by CJI Ranjan Gogoi and resigned in protest after the collegium refused to reconsider its decision.

Advertisement

Another point of friction between the executive and the judiciary relates to clearing files about the appointment of judges. Both sides have accused each other of delaying the appointment. On November 28, a bench headed by Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul warned the Union government against “frustrating the entire system” by delaying judicial appointments.

Consider the case of senior advocate Saurabh Kirpal, a member of the LGBT community, whose name was recommended by the collegium for the Delhi High Court in November 2021. The government has not cleared the file as yet. Sometimes, the Court digs in its heels. In 2018, the Supreme Court collegium recommended Uttarakhand Chief Justice K.M. Joseph, who had earlier quashed the Union government’s decision to impose President’s rule in the state, to be brought to the apex court. The Centre sent the file back with adverse remarks, but it had to concede after the top court held its ground.

Advertisement

Lokur rejects the government charge that the delay is caused by the Collegium, saying, “Consider how the government is playing with the appointment process. Appointments are delayed, recommendations are rejected, recommendations are shelved and so on. Would this be possible if the judiciary was dominating? The time has come to open up all the files of the government and the collegium to scrutiny. Let the truth be out.” It will spill the beans if these files are put in the public domain.

For instance, Justice Akil Kureshi, former chief justice of the Rajasthan High Court, was never recommended to the Supreme Court. The legal fraternity suspected that it was because he, as then Gujarat High Court judge, had remanded Amit Shah, the then state home minister, to police custody in the Sohrabuddin fake encounter case. In his farewell speech this March, Kureshi made his stand clear, saying, “Regarding changing my recommendation for chief justice of the Madhya Pradesh High Court to the Tripura High Court, it is stated that the government had some negative perceptions about me based on judicial opinions. As a judge of the constitutional court whose most primary duty is to protect the fundamental and human rights of the citizens, I consider it a certificate of independence.”

Advertisement

He was not alone. In February 2020, Justice S. Muralidhar of the Delhi High Court was transferred overnight to the Punjab and Haryana High Court, after he chastised the Delhi Police for not registering FIRs against BJP leaders who had allegedly made hate speeches that provoked riots in the city.

Apart from such stellar instances of judges holding their ground, several judges have also warmed up to the government. CJI P.N. Bhagwati is remembered for introducing the concepts of public interest litigations (PILs) and judicial activism. But he was also part of the bench that had, in the ADM Jabalpur case, held that a person’s right to not be unlawfully detained can be suspended during the Emergency. If the judgment greatly helped the then prime minister Indira Gandhi, it must be noted that Bhagwati had written a glowing letter to her after she led the Congress party to victory in the 1980 elections. “There should be some friction between the judiciary and the government. I am more wary when things go very smoothly, when it is too well-oiled. Things become different when personal interests come in—mera aadmi lagna chahiye (my man should be appointed),” says Gupta.

Advertisement

There are other reasons for friction as well, most notably PILs and bail petitions, the instances when courts question government policies, grant bail to government critics or entertain petitions unfavourale to the government of the day. Rijiju specifically named “frivolous PILs” and “bail applications” that “cause a lot of extra burden” to the apex court.

The tussle between the two wings is not new. Soon after the Republic was founded, the Nehru government stood against the judiciary, which had struck down several of the new laws related to reservations, zamindari abolition and so on. “It is impossible to hang up urgent social changes because the Constitution comes in the way,” Nehru wrote in apparent exasperation to chief ministers, underlining the need to introduce “a change in the Constitution”. With an aim to supersede the courts, he brought the first amendment that substantially altered the text of the Constitution just 15 months after the country had so proudly adopted it. “In fact, so far did they stray from the original that India’s pre-eminent legal historian Professor Upendra Baxi called it ‘the second constitution’ or ‘the Nehruvian constitution’,” writes Tripurdaman Singh in his book Sixteen Stormy Days.

Advertisement

However, the tussle has now reached difficult proportions. “The so-called confrontation between the executive and the judiciary is age old. Earlier it was generally polite, with some terrible exceptions. Today, it is generally impolite,” says Lokur.

Then, we are not in 1950 when the courts were summarily quashing government legislations. “What I find striking about these weekly executive attacks on the Supreme Court is that over the last seven-or-so years, the Court has given the State the easiest ride it could want. Not once has the Court actually struck down something in a high-stakes case,” tweeted constitutional scholar Gautam Bhatia. He listed several cases, such as Aadhaar, FCRA, PMLA, Article 370, electoral bonds, PM Cares Fund and demonetisation, among others, which were either “upheld, not heard, evaded or heard when it no longer mattered”.

Advertisement

Any attack on the court in bad faith erodes the trust in the judicial system, undermines the rule of law and leads to anarchy. If the government is seriously concerned about pending cases, the first step is to improve the infrastructure of the lower courts, the other is to evolve a judicial system that leads to stronger high courts, so that the SC does not remain the most coveted pedestal. Significantly, under Article 124, a Supreme Court judge is mandated to be appointed by the President of India after consulting the judges of the Supreme Court and high court. It reflects an era when high court judges towered high and were second to none. “At that time, there were several justices in high courts who never wanted to come to the Supreme Court. Who will consult a high court judge today, because they themselves are in a race to reach the Supreme Court,” says Gupta.

Advertisement

Perhaps, the bigger issue is inclusivity, bringing in diverse communities and caste groups, and also ensuring that the judiciary does not become a family enterprise. In November, National Lawyers Campaign for Judicial Transparency and Reforms filed a writ petition in the apex court contending that “the collegium system of appointment of judges has resulted in the denial of equal opportunity” to various eligible candidates. The petition noted that of the 33 judges in the Supreme Court, as many as 28 were either relatives or juniors of judges of the Supreme Court and high courts, or of senior advocates, the advocate general, the Lok Sabha speaker, governors and members of Parliament.

Advertisement

Unless the issue gets resolved, the highest court may continue to attract criticism. In his writings, former RSS Sarsanghchalak M.S. Golwalkar often eulogised the “institution of Panch Parmeshwar”, a traditional system to deliver justice at the local level. The comparison of a group of elderly people with God reflected the pedestal on which the Indian civilisation placed the justice delivery mechanism.

Gauge the crisis by the recent cover of the RSS-affiliated weekly Panchjanya has on the Supreme Court. The somewhat unfair essay criticises the top court on several grounds and compares the Court’s defence of the collegium system with “a woman accused of murdering her husband pleading mercy on the ground that she is a widow”.

Advertisement

Uncharitable words, that also pose a question to the Republic.

(This appeared in the print edition as "The Jarring Sound of Friction")