Self-Respect

Field,

fallow land,

hunger,

self-respect.

It stops there.

Everything stops there.

Recipe adapted from

G. Kalyana Rao’s Untouchable Spring (2010)

In September 2016, I arrived in Gwangju, South Korea, for a short art residency. One of the first conversations I had with our coordinator Saeha was about food. She was concerned about what I would eat for the next few months because I was Indian, and therefore, in her mind, didn’t touch beef—a staple in Korean cuisine. It had been just over two months since seven members of a Dalit family in Una, Gujarat, had been tied and beaten with sticks, rods and knives by gau rakshaks. The family had been skinning the carcass of a dead cow, a job that had been forced on them for generations because of their caste status. With the newly-enforced beef ban, however, self-appointed cow protectors could—and indeed, did—accuse Muslims, Christians and Dalits of killing cows, and openly attack them with impunity.

Advertisement

I assured Saeha that I wouldn’t have a problem eating Korean food. Her concern was put to rest, but I couldn’t stop thinking about her assumption. I kept going over what was happening in India. The video footage of the lynching played on a loop on every news channel, and then what followed—protests and rallies comprised of thousands, retaliation by police and upper caste communities, killings, suicides, pledges by Dalit people to give up caste-based jobs, and mass conversions to Buddhism.

Advertisement

My extended Buddhist family, for the most part, eats vegetarian food. Consuming chicken, mutton or seafood is occasionally acceptable, but any mention of beef or pork is a topic to be ignored. As a child, I assumed this was to do with our religion. As I grew up, my family history, my parents’ social work, and the reality of the caste system that we were engulfed in became more visible every day. It left me with more questions than answers, and when I began making art, I found myself constantly grappling with these questions in my practice.

ALSO READ: Beef In The Land Of Humans

Una, combined with Saeha’s question, pushed me to think about Dalit food practices more seriously. What is Dalit food? What makes food Dalit? What does it comprise? Is it only associated with meat-eating? What if a meat-eater stops eating meat? Do they stop being Dalit? Will a non-Dalit accept them as one of their own? What about eating vegetables, chapatis, rice and dal? Is the food Dalit or the person that eats it that makes it Dalit? Is everything I eat Dalit food? What about when I share food with my upper-caste friend? Is she now Dalit? Am I now not Dalit? Does she taste the meal we made together in the same way that I do?

Advertisement

ALSO READ: Food Apartheid: Non-vegetarians Not Allowed!

I spent a year reading everything that mentioned caste, food, literacy and power. Two texts in particular helped provide a grounding to my research: Anna He Apurnabrahma (2015) by Shahu Patole and Isn’t This Plate Indian? Dalit Histories and Memories of Food by the Gender Studies Class of 2009 at Pune University. Patole’s book, as far as I know, is the first published Dalit cookbook in the country. It is a record of a range of recipes common to the Mahar and Mang communities in Marathwada, and the writer combines them with his personal memories and lived experiences as a Dalit. His recipes make space for adjustments related to the availability of ingredients at hand, and are particularly sensitive to matters of hunger and necessity, backed with references to food practices in ancient Hindu texts. Isn’t This Plate Indian? brings together a range of case studies and recipes of Dalit people in Pune University, with an introduction that delves into questions of what ‘Indian’ food comprises, cookbooks and their socio-economic and caste contexts, the lack of a conventional Dalit cookbook, access to literacy and documentation, and—what has now become my particular area of interest—excerpts about food in Dalit literature.

Advertisement

ALSO READ: What Ignites Hatred In The Belly?

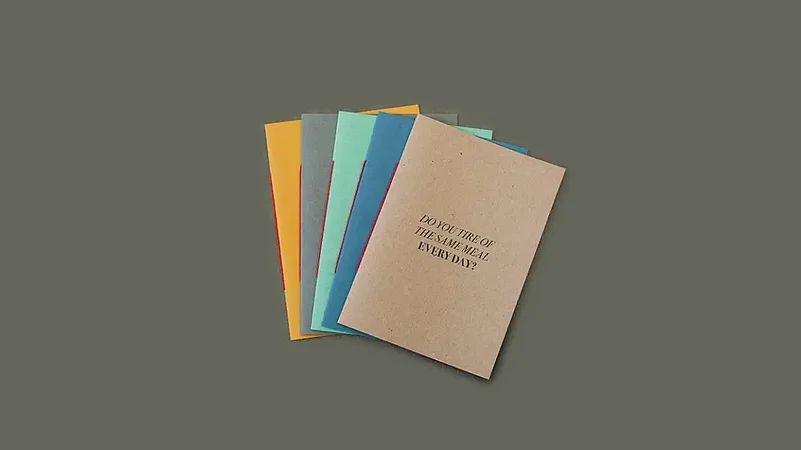

In 2017, I put together my first recipe booklet, Is Hunger Gnawing At Your Belly?. It was based on Laxman Gaikwad’s moving autobiography Uchalya (1987), borrowed from my parents. I underlined every mention of food and water in the book, noted them down, changed the perspective from first person to second, and broke the prose down to fragments that ultimately resembled something between recipe instructions and poems.

Advertisement

ALSO READ: Mid-Day Meal Scheme: We Need No Politics

Recess

Skip school during recess.

Look for beehives in the woods,

nests of pigeons.

If you come across an egg,

smear it with cow dung.

Boil it and eat it.

Always keep a catapult

and a match-box

in your school bag.

Kill pigeons and khaduls

with the catapult.

Roast them.

The next day,

Guruji might beat you

for skipping school.

Suffer it meekly.

Recipe adapted from Laxman Gaikwad’s Uchalya (1987)

Daya Pawar, Urmila Pawar, Bama, Sharankumar Limbale, Namdeo Nimgade, G. Kalayana Rao, Baby Kamble, Eknath Awad, Sujatha Gidla, Siddalingaiah, Laxman Mane and Laxman Gaikwad are some of the writers whose works have become the backbone of my research. I didn’t learn about caste at school. I learnt much of it at home with my family and through social interactions. But certain topics are still too painful to talk about with my loved ones. What if I open up an old wound? What if I don’t know how to fix it? What if I accidentally reveal what someone has chosen to hide?

Advertisement

Dalit writers, many of them the first generation to go to school, have painstakingly chosen to write their life stories, and in doing so, have been able to voice not just their own experiences, but also of those of millions of Dalits across the country, as well as those of our ancestors. Many of these memoirs are filled with writing about food, making the link between the stomach and oppression very clear. Experiences of hunger, begging, shame, guilt and eating leftovers weave into ones of feasting, joy, delicacies and happiness, revealing the complex and deep-rooted links between food and caste.

Advertisement

In drawing out these ‘recipes’ through writing, looking through family photos, and more recently, making ceramic installations that resemble food objects, I hope to keep learning and unlearning. I recognise the responsibility I have towards my community, and to myself, in treating these themes with care and dignity. It has never really been about the food or how delicious or exotic the cuisine is. These recipes are not meant to be followed, because they cannot be lifted out of their context. What they can do, I hope, is reveal to the reader just how deep the roots of caste go, such that even the simplest activity of drinking a glass of water or eating a plate of food is coloured by it.

Advertisement

(This appeared in the print edition as "Caste On A Platter")

(Views expressed are personal)

ALSO READ

Rajyashri Goody is an artist based in Amsterdam