A murder of crows circles around the denuded branches of a tree against a background of the grey sky, portrayed in spare strokes. The sketch, titled Crows, was made by Amitava Kumar in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 2019. The professor of English at Vassar College had been preparing to rush to class, when the crows, uncommon in those parts, had appeared out of nowhere and started wheeling and cawing outside the window of his house. He decided he could not go to campus without attempting a sketch. As a draughtsman, such moments are gold and he can’t resist translating them on paper. “I work quickly and try to catch a feeling or mood that keeps that particular moment alive,” Kumar tells me when we meet in Delhi.

Advertisement

Crows is among a clutch of drawings and paintings tucked between the pages of The Blue Book: A Writer’s Journal (HarperCollins India), Kumar’s ‘panoramic portrait’ in watercolours and words of how he experienced the pandemic. The accompanying text narrates the story of how the sketch came into being. It also includes a short commentary on the importance of having specific knowledge (of birds and trees, for instance) in order to write well. William Maxwell wrote: “After forty years, what I came to care about most was not style, but the breath of life.” When people ask Kumar about his favourite pieces of writing advice, he remembers this, always. In Crows, he was not bothered about style. He just wanted to catch “life on the wing, as it were.”

Advertisement

For the past few years, Kumar has been painting watercolours: Tulips in bloom that he first saw in Srinagar, Kashmir, “where now death blossoms like flowers,” forsythia bush ablaze with colour in the morning light, and trees of his native city, Patna. He also uses gouache (“for its opacity”) and ink on newsprint: for his novel about the news, he wanted to make art that interacted with it. Drawings and writings occupied his imagination when he was working on his novel, A Time Outside Time (Aleph, 2021), which shows us what fiction can do in the post-truth era. “Like my novel, these drawings are a response to our present world—a world that bestows upon us love and loss, travel through diverse landscapes, deaths from a pandemic, fake news and, if we care to notice, visions of blazing beauty,” he writes in The Blue Book. In A Time Outside Time, he brings news to novel-writing and makes us feel it “fresh like blood on the bandage.” In today’s novel, he says, news should be like that.

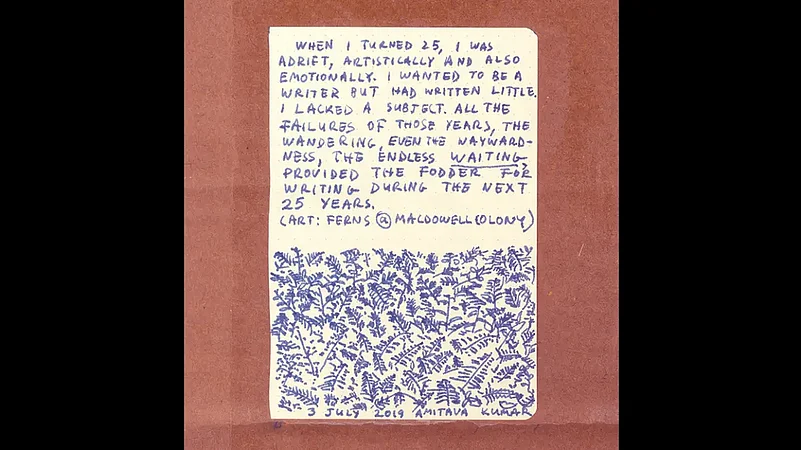

Prose borne out of a mishmash of influences has been Kumar’s preoccupation. Clippings, quotes, sketches and notebooks are vital elements of his process to gather material for his books. His 2017 novel, The Lovers, published in the US as Immigrant, Montana—a meditation on love beyond and across dividing lines—is a patchwork of story and reportage, anecdote and annotation, picture and text, fragment and essay. The diaries he has kept over the last two or three decades have helped him write all his books. The Blue Book is both a diary and a work strung together with diary entries. If you have nothing to write, observe the world and record its ways, he urges us in the book. “When we do that, we are recording our own history.”

Advertisement

The style of The Blue Book is a nod to John Berger, who has been central to Kumar’s creative endeavours as a writer and artist. He had discovered Berger’s political and sensual world as an undergraduate in Delhi. A Seventh Man (1975), in which Berger and Swiss photographer Jean Mohr reflect on what it means to be a migrant worker in Europe, inspired Kumar’s first genre-bending work, Passport Photo (2000), which combined poetry, cultural criticism and photography to meditate on the everydayness of the immigrant experience; it symbolised the quest to find new poetics and politics of diaspora championed by post-colonial theorists like Edward Said. “I am touched by Berger’s attentive eye and his unaffected ease; wavering outlines drawn with pen and texture added by rubbing a finger wet with spit,” writes Kumar, who discovered Bento’s Sketchbook (2011) at Michael Ondaatje’s Toronto home during a book tour a couple of years ago. Since then, he has been trying to draw like Berger, every day.

Advertisement

Besides his meditations on Spinoza, Bento’s Sketchbook features Berger’s drawings of irises (‘Irises are like prophecies: simultaneously astounding and calm” he tells us), plums, a bicycle, and a sketch of a 15th-century painting of a crucifixion. “How does the impulse to draw something begin?” Berger poses this question which he elaborates in the book through text and drawings, a style Kumar follows in The Blue Book. Writers and artists like Berger who work with text and images have been his favourites. He collaborated with Teju Cole on an ekphrastic project in which the latter’s photographs intersect and interact with the works of other artists, including Susan Sontag, whose works traversed diverse disciplines. Bento’s Sketchbook revealed Berger’s keen sensibility and new ways of seeing. The Blue Book, shot through with remarkable empathy, goads us to engage with the world around us in a meaningful manner. To see better. To write better.

Advertisement

A collage of the personal and the political as Kiran Desai has called it, The Blue Book marks Kumar’s turn to the visual. It is his personal register of observations, textured with his memory of people, places and things. If his asides and anecdotes take us to the moments he has experienced, his paintings seem to say, “I was here, I saw this.” With it, he joins the pantheon of poets and writers who also painted: Derek Walcott, Elizabeth Bishop, Victor Hugo, Clarice Lispector, Herman Hesse, Federico Garcia Lorca, and, closer to home, Rabindranath Tagore. If his journals are a vehicle to the creation of a sense of selfhood, as it was for Sontag, his painting is a form of keeping a diary, as it was for Picasso.

Advertisement

The question Kumar, 59, asks himself more frequently these days is: how to be more of a human than a ‘gadget’? In early 2021, when seated at his desk one morning, he asked himself how would he like to greet the future? “In the days that are left to me, who is it that I want to be?” he recollects in The Blue Book. When he reads, say a story by Alice Munro, Anton Chekhov, Ismat Chughtai or Vinod Kumar Shukla, he enters a “rarer state of mind” in which he pays attention to the inner workings of the world. It’s when he reads, with a sense of focus and empathy that he feels as if “my humanity has been restored”. Bringing the same level of commitment to the craft of writing impels him to conclude: “I am a writer; so, every day I write. The days I am given are only for writing.” Drawing and painting make him feel in touch with the world around him.

Advertisement

Kumar arrived at drawing and painting decades ago, when he tried his hand at watercolours as a schoolboy in Patna. However, he found the results unsatisfactory. A few years ago, he started with his son’s box of watercolours. During the lockdown, when his kids—son Rahul and daughter Ila—were at home, he thought he should design something to engage them. He urged them to write, even if it was just a paragraph, and draw every day. As he started to draw, the engagement grew. He began thinking about interacting with the news, which led him to draw and paint on newspapers.

Advertisement

Elizabeth Bishop, who also attended to Vassar College, has influenced its current professor. Kumar finds her paintings of Brazil, displayed at the college gallery, tremendously fascinating. Although Walcott’s watercolours look ‘a little improvised,’ they seem to him full of life. Kumar says he likes the fact that your art could be lacking, but because it’s lacking, it’s alive. Picasso’s works appeal to him for their realism and for their sheer brilliance of imagination. He is drawn to the rigour and routine of Japanese-American conceptual artist On Kawara, who produced about 3,000 canvases that can be distinguished from each other only by their unique dates.

Advertisement

There is a little story behind the title of The Blue Book, which juxtaposes the gloom of the pandemic with the vibrant colours of foliage. In the Patna school Kumar studied in, the report cards would be called ‘The Blue Book’: “Since I was not a good student, I was scared of it. I am taking some agency back by making a different kind of blue book, which doesn’t show the poor percentages.” The Blue Book and A Time Outside Time take forward Kumar’s thesis that literature arises from artifice and that ordinary life can be transformed into art. If purists find fault with his artworks, he has a counterpoint: The priority for him is not to make it perfect, but to attempt to capture what Maxwell called “a breath of life.” In these paintings, he wanted to create an interaction between language as words on the page and language as images. A space between words and image “where the reader’s imagination can dance”.

Advertisement

Living in the US, Kumar has stayed connected with India. Most of his works draw on this connection. Some of his paintings depict the disturbing news of lynchings and plight of migrants during the lockdown that reached him: “The world comes to us in the form of bad news.” A montage shows a migrant family stranded by the roadside as, in another image, petals drop from the sky (at government orders to honour medical workers).

Does Kumar see his divided life feeding into his fiction and non-fiction? “One cannot know for certain. Of course, different circumstances produce different work. The real question to ask here is that if I hadn’t become a writer, would I have produced this art? I think the answer is no,” he says. Being a writer then is congruent with his practice as an amateur artist, and a compulsive diarist. Like a writer who keeps a diary and, therefore, has more than what he or she has in their published books, he has more paintings other than those are part of The Blue Book. Should we look forward to his art exhibition next? Not quite. For he would rather do a book: “I’m a books guy who is trying to change the look of the book.”

Advertisement

“We who draw do so not only to make something observed visible to others, but also to accompany something invisible to its incalculable destination,” writes Berger in Bento’s Sketchbook. Perhaps Kumar’s own aim is similar. He wants to freeze his observations on canvas and paper, from the fleeting moments. “All good writing must turn its face to the world,” Kumar writes in his style manual Writing Badly is Easy (2019). A writer, forever searching for resonances across diverse landscapes, must always have an eye on the world he/she inhabits. As Kumar does. His greatest wish is to be someone who pays attention. VS Naipaul taught him to avoid the abstract and always go for the concrete. Over the years, he has found his own mantra: ‘Write every day, and walk every day.’ His routine includes a modest goal of writing 150 words daily and mindful walking for 10 minutes. He asks his students to follow the same regime. “Imagine, when you walk, that flowers are blooming under your feet,” he tells them.

Advertisement

In his conscentious notes in The Blue Book, he remembers the protests over CAA and NRC, as well as the 2020 Delhi riots. We should remember, he writes, what was done to our fellow human beings and fight for justice on behalf of those so grievously wronged. The central conceit of art is that it should move readers/viewers and leave them altered and changed. While Kumar has not fully bought into that worldview, he does want to remember. All he wants to achieve through his words and works of art is that they are able to keep alive a memory.