For the past 10 months, Kyiv-based graphic artist Olesya Drashkaba has been making regular entries in a grim notebook that she calls ‘War Notes’. She is keeping tabs so that she could have an exhibition of her collected wartime artworks “once the Ukrainians win the war”.

The artist is one of the millions of Ukrainians whose lives changed following the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. “I am a professional artist and curator so, from the very first day of the invasion, I had no other means of expressing my emotions and feelings but to paint and write my thoughts about what I saw around me during the course of the last few months,” Drashkaba tells Outlook in an email interaction.

Advertisement

Two months into the war, she and a few other artists decided to come together and start the Sun Seed Art project. Kateryna Melnyk, project manager at Sun Seed, tells Outlook that the principal goal of the project is to spread Ukrainian war posters and graphic art abroad in order to strengthen the Ukrainian artistic voice in the international community and inform public opinion about what is happening in Ukraine. “Each of the 14 member artists of the project has had distinct experiences of the war and each of them interprets the violence and injustice they see in different ways in their art,” says Melnyk.

Advertisement

While some posters use crude jokes and loud language, others are delicate and more narrative. Artist Andriy Yermolenko, for instance, has been working with war posters since 2014, and his works provide a laconic, documentarian reflection of many key events that have transpired in this war. Maksym Palenko’s works are often sarcastic, but deeply lyrical, when speaking of the Ukrainian military and culture. Symbolically, though, they represent the same idea. “All of them are talking about an incredibly powerful force rising up to accept this challenge of war,” Drashkaba, who has also been an art lecturer since 2010, tells Outlook.

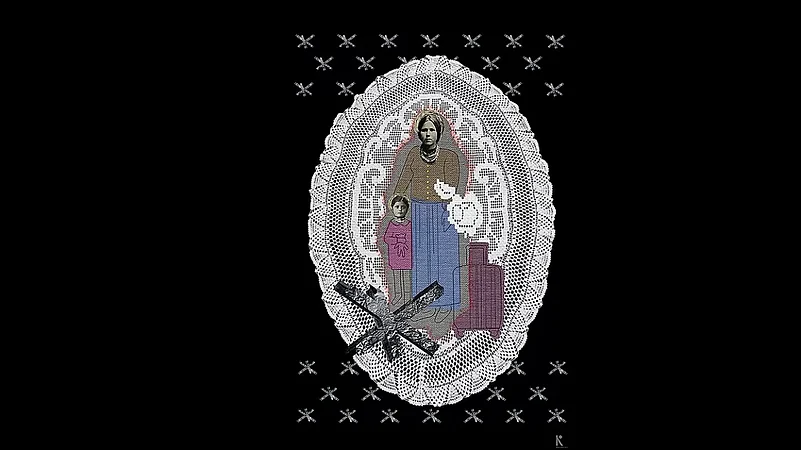

The works also reflect not only the current war but also the war that was fought a hundred years ago when Ukraine lost the War of Independence to the Soviet Union. Millions of Ukrainians were killed due to repression and state-induced famine. Since the Russian occupation this year, many artists and people working in the field of culture have actively reflected on the history and mythology of Ukraine, drawing parallels between historical events, works of art, tradition and folklore. Kateryna Lisova’s works, for instance, are the result of a collage of folk art and the modern realities of war.

Many of the artists also look at the feminist response to war. Svitlana Grib’s work delves into woman-centred images of this war: from a woman who is waiting for her bridegroom to a witch—a common image in Ukrainian folklore of the 20th century—who conjures victory over the enemy. In one of her artworks, Grib illustrates how war has changed the roles for women. From greeting guests with bread and salt, as is the custom in Ukraine, the poster depicts women greeting uninvited guests with hand-made weapons called ‘Molotov cocktails’.

Advertisement

Anastasiya Pustovarova’s image of Alyonushka, a popular figure in Russian fairy tales that symbolises feminine innocence and chastity in Ukraine, is seen carrying bombs instead of buckets of water. Drashkaba’s artworks are also replete with feminist imagery and often draw parallels between women’s bodies and the socio-political impact of territorial conflicts.

One of her posters depicts the body of a woman covered with tattoos showcasing the words from Ukrainian artist Stasik’s song, ‘Lullaby For The Enemy’. The artwork gives the message: “This is the land you’ve always wanted. Now you get yourself mixed with it.” It implies that those who came to kill will die on the land they came to conquer. There are ornaments on the body that have echoes of traditional Ukrainian ornaments, while resembling the human circulatory system. “A woman today in this war is the most vulnerable and at the same time the strongest figure. Thirty per cent of women serve in the Ukrainian Army. Women are also engaged in volunteering, providing medical aid and creating many humanitarian support projects,” Drashkaba says.

Advertisement

But even those not directly involved with the war effort are part of the war. Millions of women are waiting for their husbands, sons, brothers and friends fighting the war every day. “I really believe in the emotional power of a woman, both in the power of her support and in the power of her curse and rage. My painting shows an angry woman whose words are strong. She does not want revenge, she only wants justice and the guilty to be punished,” Drashkaba adds.

Advertisement

Kyiv-based activist and entrepreneur Natalya Popovych, co-founder of the project, co-founder of Resilient Ukraine and founder of One Philosophy, says that Russia’s purpose in what she calls a “centuries-long war” is not just to take over Ukrainian territory but to break Ukrainian resilience and impose cultural hegemony by destroying the national Ukrainian identity and statehood. However, the activist claims that Ukrainian art is the ‘nation’s vaccine’ against the Russian brutality.

In 1937, the 20th anniversary of the October Revolution of 1917, noted Ukrainian playwright Mykola Kulish, who is widely regarded as the father of the Soviet–Ukrainian drama, was murdered in a mass execution of political prisoners in Sandarmokh by Soviet forces along with 289 other Ukrainian writers, academics, artists and intellectuals. Kulish’s work had satirised the political and social impact of the Soviet policy of Ukrainisation and strived to demythologise the Bolshevik uprising.

Advertisement

Eighty-five years later, musician Yuriy Kerpatenko, who incidentally worked at a theatre named after Kulish, was shot dead inside his home in Kherson by Russian troops. The chief conductor of the Kherson Music and Drama Theatre had allegedly refused to perform at a Russian-sponsored ‘holiday concert’ held to celebrate the victories of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Though his death evoked fear, it has brought out a new zeal among artists. Oksana Lyniv, award-winning Ukrainian music conductor and founder of the Youth Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine, tells Outlook in an email that Kerpatenko’s death was a reminder that accepting the occupation was not an option. “Kerpatenko’s killing was one of the many tragic deaths of Ukrainian musicians and artists this year. This for me is the clearest evidence that we have no alternative but to liberate our land from the occupiers. There is no going back,” Lyniv categorically states. “Occupation means the dictatorship of the aggressor and as we already know, it brings only destruction and death. We have to fight for our freedom, freedom of self-expression, freedom of our culture,” she adds.

Advertisement

While many of the young musicians, part of the YSoU, have now become refugees, Lyniv has tried to do her part by promoting Ukrainian composers across the world during her concerts. “Ukrainian music is heard all over the world. This is our resistance and survival,” she adds. The defiance of artists like Kerpatenko and Lyniv reminds one of the Italian music virtuoso Arturo Toscanini, who was once beaten black and blue by the Blackshirts, a militant group of ‘volunteers’ working for the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, after he refused to perform the Giovinezza, the official anthem of the fascist party, at a concert in Bologna.

Advertisement

In Ukraine, Putin seems to have learned from the ghosts of despots past. This time, fewer Toscaninis are living to tell the tale. The PEN Foundation notes that at least 35 persons including historians, poets, graphic designers, ballet dancers, professors, scientists, tour guides, authors and other Ukrainians have been killed either at the frontline or in stealth, such as Kerpatenko. “No one is safe now in Ukraine, especially artists,” Drashkaba adds, as an ominous reminder.

The truculent artists, however, seem to be driven by the everyday bravery of ordinary Ukrainians who believe in the same vision of victory as they do. Seven weeks into the invasion, a group of over three dozen graphic novelists, artists, caricaturists and creators, including several Eisner Award winners, got together for a charity comic book titled Comics for Ukraine: Sunflower Seeds.

Advertisement

The title is perhaps an ode to the resilience of the Ukrainian people. On February 24, the day Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, an elderly woman reportedly approached Russian soldiers in Kherson. Handing them some sunflower seeds, she said, “You came to my land with weapons. At least put some seeds into your pockets so that the sunflowers will grow out of you later.”

These words have become a metaphor for the strength, defiance and hope for countless Ukrainians. By capturing these acts of resilience and resistance in their art, Ukrainian artists hope to convey the truth about the war in their homes to the whole world. “This is not a proxy war or a local conflict—it is a cynical attack on an independent country, attempts at the genocide of an entire people, and we are defending our land, our independence and freedom,” Drashkaba says with finality.

Advertisement

The artist, however, adds that it is not all anger and sorrow. Yes, the work she and thousands of Ukrainian artists are producing is resistance art. But a very important feature for Ukrainians in resistance is humour. “We joke a lot these days,” she says. Amid the sound of bombs falling, laughter, she claims, has a therapeutic effect.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Art & War")