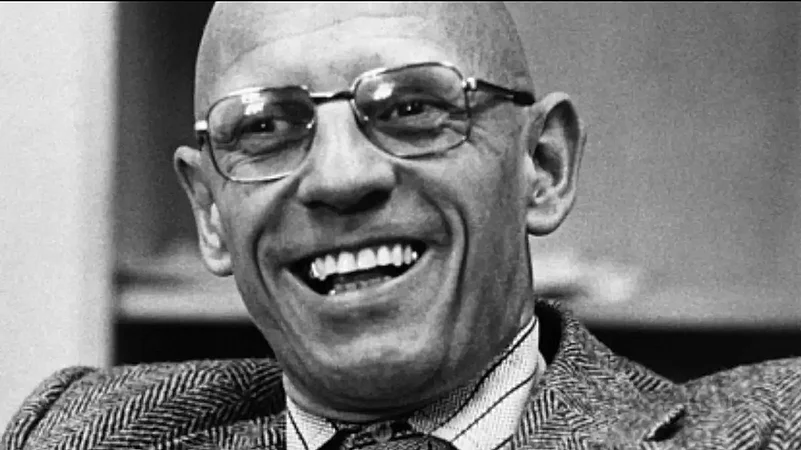

According to science, the evolution of the universe and human civilisation is the result of a clash of forces. Therefore, in each phase of human civilisation, discourse of power has been playing a pivotal role in the speech act. However, there are different expositions of power in different governments, nations and institutions of the world which are less similar and more antagonistic. Michel Foucault's (1926-1984) significance in modern times is also due to the fact that he illuminated the positive repercussions of power. In Foucault's view, the mood for power is not always inimical. Therefore, the disseminate of power is not a means of circumscribing man, nor does it force man to act against his desires.

Advertisement

The rudimentary premise of Foucault's philosophy is that power, like all other things, is characterised by fecundity. For Foucault, the statement, whether social or historical, literary or cultural, is a basic unit of dialogue. That is why he attaches great importance to the statement in his analytical process. Here, Foucault uses the statement in a very idiosyncratic sense, subtracting it from its traditional conception. Enounce (statement) is a source of interesting meaning for Foucault. Which makes speech, accent and speech acts revelatory. But this does not mean that 'statements' are glancingly pigeonholed by autonomous attributes of pronunciation, accent and speech functions. Rather, they form a kind of doctrinal circle that proves what is revealing and what is dross. These are principles by which words, accents and verbal actions are separated from the essence of meaning.

Advertisement

Foucault also elucidates "statements" as events that may or may not be based on these principles. He says that grammatically correct sentences can be inane while some grammatically incorrect sentences can have many meanings. Statements hinge on the discourse situation where they outcrop. Therefore, Foucault recognises dialogue as a large assemblage of statements. This dialogue is the main subject of his analysis. But he does not disaffirm the other factors of analysis.

Foucault not only exposes the hidden truth in the sentence but also seeks to trace its lost meaning. In this process, instead of a skin-deep meaning, the subordinate meanings of the dialogue become prominent, which are assumptive in their nature. Foucault also makes the applicative and coherent situation of existence a subject of study.

The search for the deeper meaning secluded within the dialogue leads Foucault to structural thought. But unlike run-of-the-mill structural thinkers, he does not base the genesis of dialogue on uniformity, but on the basis of differentiation. Therefore, Foucault is not convinced that any statement in the argumentative organisation can be examined beyond its practical application. This is where Foucault emerges as a historian. Because he seems to be in favour of analysing all kinds of statements in their historical context.

This organisational structure of Foucault's work, and its rational principles, give a unique identity to the basic unit (statement) of dialogue. While Foucault's ideological discourses have been well-received, some scholars, such as Jacques Derrida (1930-2004), Hayden White (1928-2018) and Noam Chomsky (1928-), have criticised him. Their main objection to Foucault is that while he rejects the values and philosophies of Enlightenment, he also secretly trusts them. Foucault has repeatedly stated that he is a strong espouser of human freedom. Therefore, his philosophy has always been propitious.

Advertisement

The literature of most of the developed languages of the world, in spite of its self-sufficiency, seems to be a captive of the political system which Foucault acknowledges as the source of power, which draws a clear line between ruler and subject. This means that literature in itself is not as self-sufficient as it seems. Whatever the disadvantages of skepticism, one of the major benefits is that it enables us to transform the darkness of our literary society into light. This couplet of the ancient Urdu Masnavi (narrative poem) ‘Kadam Rao Padma Rao’ (1421) can be seen as an example:

Advertisement

Sujaat aik nagin kujaat aik saanp

Asangat dethein khelte laap jhaanp

(A female snake of superior breed and a snake of inferior breed,

I saw two of them were hugging each other)

There is a strong sense of racial superiority and racial inferiority in relation to sujaat (superior race) and kujaat (inferior race). Similarly, there is a couplet of Daagh Dehlavi (1831-1905):

Tumne jadugar usey kiyon kah diya

Dehlavi hai Daagh bangali nahin

(Why did you address him as a magician?

Daagh is a resident of Delhi and not of Bengal)

Here, too, the regional superiority and inferiority complex of Delhi and Bengal prevails in terms of reality and magic, bound by fidelity.

From these examples, it follows that poets are more concerned with the power of their time than with the creative self.

Advertisement

(Views expressed are personal and may not necessarily reflect the views of Outlook Magazine)