In the 70s and into the early 80s, Hindi cinema turned its camera not infrequently to the study of middle-class marriage. Thoughtful films like Arth and Masoom looked at the cost that men's infidelity extracts from their wives. Yash Chopra's Silsila did too, and along with Chopra's Kabhi Kabhie, considered the challenges of marriage undertaken out of a sense of duty. Aandhi and Abhimaan, each in its own way, shed light on the ways ambition can drive a wedge between partners.

Basu Bhattacharya was obsessed with the subject of marriage, and turned out three close studies of it in a decade. In these movies – Anubhav (1971), Avishkaar (1974), and Griha Pravesh (1979) – couples strain to build their homes, to maintain their connections; they remember happier times, and reach a kind of equilibrium, however unsteady it might be. Bhattacharya's own marriage reached no such accord. His wife, Rinki Bhattacharya, has spoken in harrowing detail about the emotional and physical abuse he inflicted on her. His trilogy barely touches on that terrible kind of marital discord; only Avishkaar, which Rinki Bhattacharya has said draws on events from their relationship, portrays any violence within the marriage at all. Armchair psychoanalysis is tempting – why did Bhattacharya's careful examination of troubled marriages mostly steer meticulously clear of self-examination?

Advertisement

But speculation is not analysis, and even without insight into the director's mind, the three films present interesting text. All of them examine the tight connections between what makes a successful partnership and what makes a loving home. The concepts of marriage and home become almost interchangeable in these films, rich metaphors for one another. And in each, the marriage is threatened both by the weakening of the home, and by the invasion of the world. Together, the films observe that to thrive, a relationship needs both a sound foundation in the home and a strong rampart to face the world.

Advertisement

Anubhav opens with an explicit statement of a thesis that runs through all three films: a house is not necessarily a home. Early on, Meeta (Tanuja) sits frustrated and idle while a troupe of servants prepare meals, scrub the kitchen, and dust the furniture. After a fretful morning keeping out of their way, Meeta almost impulsively lets them all go, except the most senior, Hari (A.K. Hangal), whom she keeps on when he complains that he has known no other home than this one. Meeta scoffs in reply that with all the servants around, the meticulous flat feels more like a luxury hotel than a home. Hari, understanding, resolves to address Meeta as "Bahu." And so Meeta begins to build herself a home by taking on her own domestic work.

The world intrudes when Meeta's husband Amar (Sanjeev Kumar) hires her old flame, Shashi (Dinesh Thakur), as his right-hand man. As Shashi spends more and more time in Meeta's carefully-managed home, Meeta becomes increasingly uncomfortable. Amar, in the dark about their prior connection, cannot comprehend Meeta's hostility toward the young man. In response, he becomes hostile to her, and Shashi begins to realize that he is a threat to the home Meeta is working so hard to create.

Avishkaar recounts one restless night in a very nearly broken home. During the long night both Amar (Rajesh Khanna) and Mansi (Sharmila Tagore) remember happier times, and many of these flashbacks take them outside their home. Inside, though, in their present, the atmosphere is poisoned. Amar and Mansi bicker and provoke each other. In scenes that become increasingly hard to watch, Mansi taunts Amar until he attacks and hits her. Outside their little house stands a sign, resembling a yellow traffic light, that reads "Amar Mansi ka ghar." It is both invitation and warning.

Advertisement

Over time, the corrosion within their home weakens Amar and Mansi's marriage against the intrusion of the world. The couple have married in defiance of Mansi's rageful and disapproving father (another detail from the Bhattarcharyas' life), and in this early stage, their relationship is strong enough to resist this toxic force. Later, though, Amar is tempted by a beautiful and cynical colleague with a taste for married men. On a date with her, Amar squirms uncomfortably, and cuts the date short to return to Mansi. But the flowers he brings home for her, Amar leaves on the doorstep before entering, beneath the traffic-light sign. Their threshold has become a barrier through which misery cannot escape and happiness cannot enter.

Advertisement

The third film in the series, Griha Pravesh, makes still more explicit the entanglement of marriage and home, from its title (referring to the rituals of taking occupancy of a new home) to its central couple's plan to find and buy the perfect home. This film's Amar and Mansi (Sanjeev Kumar and Sharmila Tagore) live for years in what seems to be a temporary address. Walls peel, furniture goes shabby, decoration remains sparse at best, while the couple fantasizes about their future home, always just around the corner. But that dream remains stalled, in perpetual limbo for one reason or another; there isn't enough money for a new flat, or they cannot find a suitable one. The film layers this metaphor thickly. Once Amar and Mansi's broker takes the couple to see an unfinished property, a flat in a high rise that does not even have exterior walls. The wind whips around them, underscoring the ephemerality of their dream-home, though the couple seems oblivious to the symbolism.

Advertisement

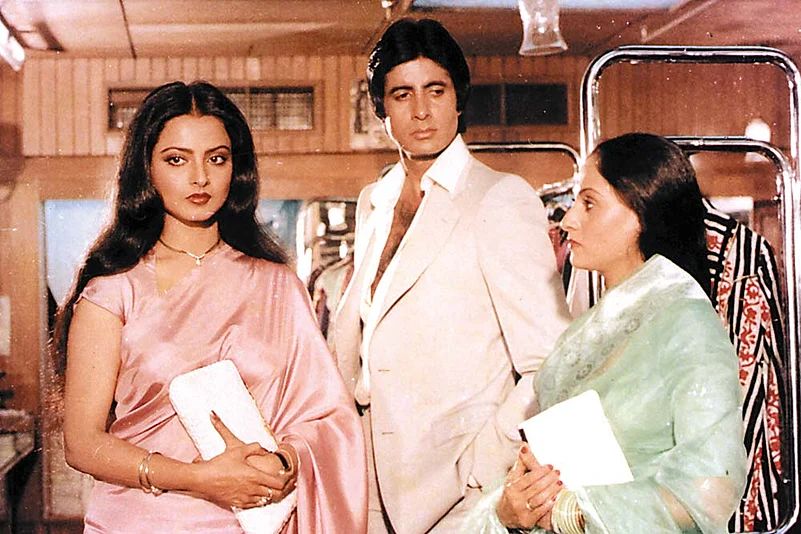

In the meantime, in the world, Amar begins an affair with a clerk from his office, Sapna (Sarika), who sets her sights on seducing Amar when he proves, at least for a time, to be the only man in the office unaffected by her tank tops. (She is a horrible character, who reinforces every misogynist justification for excluding women from the workplace with her penchant for literally inviting impropriety.) Sapna's name, of course, suggests that the rejuvenation Amar thinks she offers is just as much of a dream as that always postponed perfect home.

Learning of Sapna, Mansi demands to meet her rival. In preparation for the visit, Mansi cleans and paints their old, neglected home, hanging art on walls and adorning tables with pretty cloths and fresh flowers. The place is transformed, and now both Mansi, who has longed for more from her home, and Amar, who has craved more from his marriage, can read these signs. Bhattacharya himself may have failed to apply the message of his own films, but their meaning is clear: marriage and home are one and the same, and both require an investment of effort to flourish against the buffeting of the world.