In March, the Center told the Supreme Court that it was open to the suggestion of conducting NEET, a single window entrance test for admissions for MBBS and BDS courses, in the Urdu language from the next academic year. This has rekindled the debate on the present state and the future of Urdu language.

Every language affords its speakers the opportunity to experience the world through a distinct lens. While Hindi speakers perceive their surroundings through a vocabulary comprising Hindi words, English speakers discern worldly bustle through the English language. Every language, thus, grants a glimpse of a unique reality peculiar to that language. Increasingly, however, the Urdu language is nowhere within the eye’s line, which makes one ask: What happened to the Urdu language and the corresponding reality it afforded?

Advertisement

In pre-independence India, Urdu was the language of cosmopolitanism and distinction. Jawaharlal Nehru, one of the most revered leaders of the country, had once said, “Urdu is the language of the towns and Hindi is the language of the villages. Hindi is of course also spoken in towns but Urdu is almost entirely an urban language”. Urdu was, thus, a language of upward mobility in the period preceding independence.

However, India after independence witnessed a pronounced decline of the language. Urdu Bazaar—a major market in the walled city of Delhi—that has physically lived through the changes in the Urdu language in pre and post independence India, seemed like a good place to delve into the reasons for the decline of the Urdu language.

Advertisement

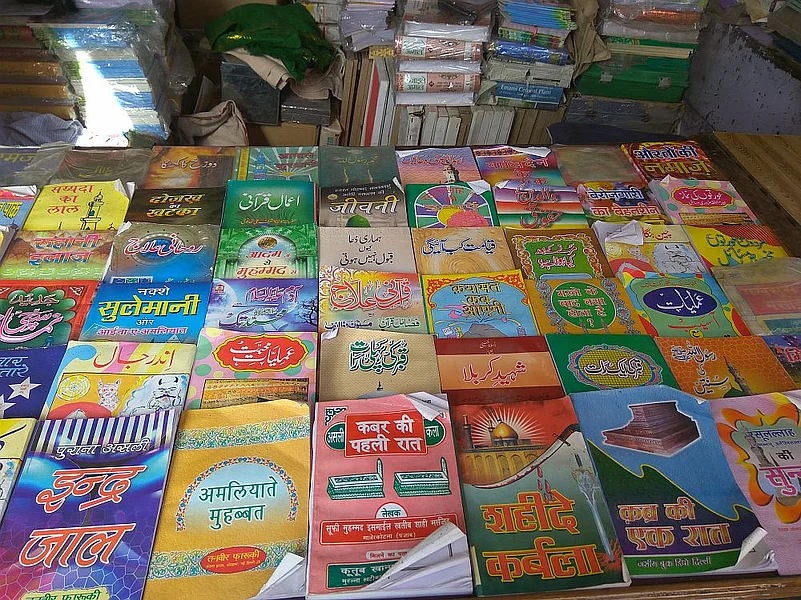

The market, displaying a selection of Urdu, Persian and Arabic books, connects the canal in the middle of Chandni Chowk to Jama Masjid. The original market was destroyed in the aftermath of the 1857 War of Independence but its name and remnants still survive in Old Delhi, where an entire lane is replete with shops that sell rare treasures in the three languages. Most shopkeepers in the market have owned their shops for generations, with some even saying that their ownership goes so far back that they do not remember the date of establishment anymore.

When asked what he thought the reason for the decline of Urdu was, a shopkeeper from the market, said: “I think the language of elite interaction has now shifted to English. And the language of the Hindus has shifted to Hindi. In the midst of it, Urdu has gotten lost”.

Another shopkeeper, sitting behind his counter on Urdu Bazaar, expressed a different opinion from that of the first. “I do not think Urdu has declined. We are speaking in the Urdu language right now”, he said. “Contemporary Hindi, after all, contains a large amount of Urdu. And if it is the Urdu script you are talking about, it is taught to all Musalmaans in madrasas. Urdu is still alive and breathing,” he said with confidence.

Well known writer and literary historian Rakhshanda Jalil expresses a similar opinion. “Urdu catches us unawares in [many] guises”, she says. “For instance, when agitations both north and south of the Vindhyas—be they university teachers or factory workers—declare ‘Inquilab Zindabad!’ (‘Long Live the Revolution’), they are simply echoing the cry of Hasrat Mohani, the maverick Urdu poet who wrote sweetly lyrical ghazals in the chastest meter”.

Advertisement

Indeed, the Urdu language does catch us unawares. Consider the last Bollywood song you heard and most probably, it will have the word ‘ishq’ or ‘mohabbat’ in it. We have imbibed Urdu vocabulary as part of our daily language and in the process, Urdu has become a part of our culture without us even being aware of it.

But as I looked at the line of empty shops that filled the street of Urdu Bazaar, I could not be as confident about the fate of Urdu as Rakshanda Jalil and the shopkeeper seemed to be. Aside from the shopkeepers themselves and at times, another friend or two, the bookshops seemed starkly empty. No customers lurked nearby. The only activity on the street was at the slaughter houses and restaurants. Why this lack of interest in the language?

Advertisement

According to veteran historian Irfan Habib, the disappearance of Urdu from the contemporary scene was triggered when the language was linked to the Muslim religion in post-independence India. “Obviously I can see why Urdu is linked to Islam since the script is derived from other Islamic languages, i.e., Persian and Arabic. But that is no reason to dismiss everything within the language as religious. For instance, how can Urdu poetry ever be religious? In fact, Urdu shayari would, at most times, contradict the Islamic religion and what it preaches” says Habib solemnly.

He goes on to detail how earlier, a mixture of Hindi and Urdu was allowed for, that mixture being the Hindustani language. “But now, this intermingling between Hindi and Urdu is strictly policed,” he says. “It is frowned upon in Hindi medium schools, so much so that if you use an Urdu word in an examination, you are liable to be penalised for it. Increasingly, there is an emphasis on the Sanskritic origins of Hindi; anything other than a pure, Sanskritized Hindi is looked down upon” says Habib in exasperation.

Advertisement

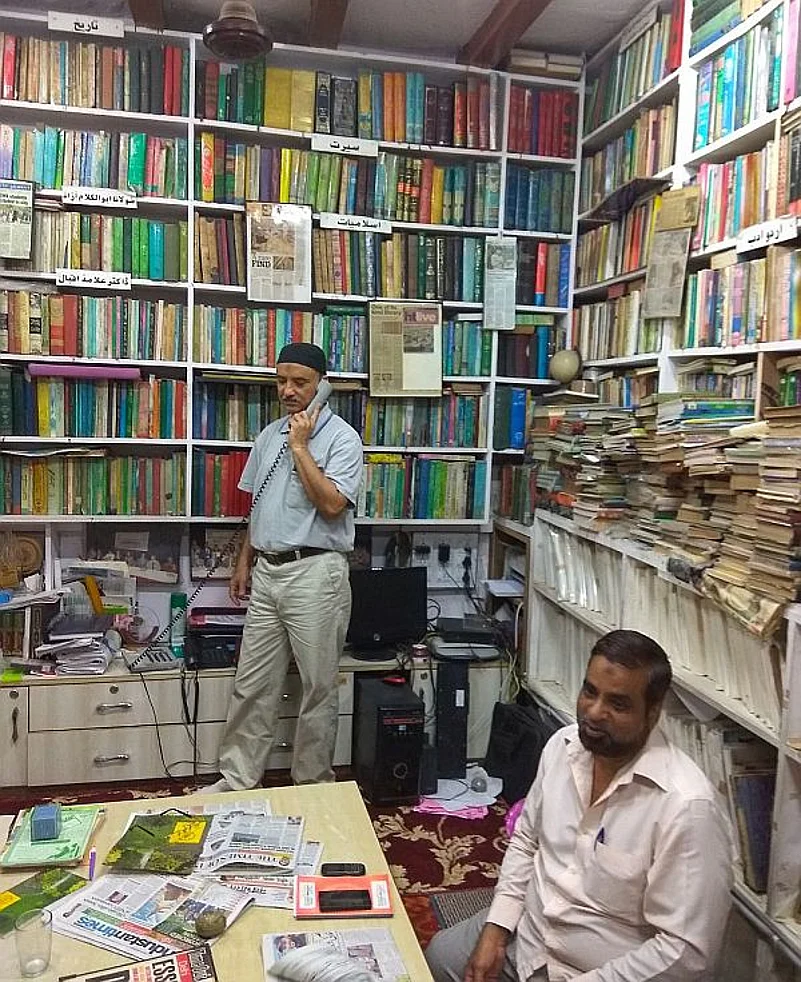

Further along the lane of Urdu Bazaar, turning right from the Peepul tree took me to Chooriwalla, home to another unique Urdu initiative. The Hazrat Shah Waliullah Library is a community effort to create a space that preserves rare books in Urdu, Persian and Arabic. Muhammed Naem, the co-founder of the NGO that runs this library explained how the NGO, in addition to preserving Urdu language and literature, also works towards sponsoring the studies of students from poor socio-economic backgrounds. The yearly budget for Muhammed Naem’s endeavour is 6-7 lakh rupees, a sum that is paid entirely out of the NGO’s own pockets since they do not accept external funds.

Advertisement

“All we ask the government for is space” said Mr. Naem in a low voice. “Kavita Sharma from India International Center had come here, and she sent a letter to the Ministry of Culture because some of these books are very rare. They need to be preserved”. He went on to explain that three times the number of books stacked in their library were currently stored in two other places. Because of lack of safe space to store these books, a lot of them fall prey to termites and rot. “I have been fighting for space to store these books for the past 13 years. But they have not helped us until now. Kapil Sibal Sahab has come here, his wife has come here. All the MLA’s and Councillors have come here. Sibal Sahab even told us that he will give us space, but he will just stay an MP for 15 years and then leave”.

Advertisement

On the suggestion that he ought to approach the Urdu Academy—a government initiative to promote, propagate and develop Urdu language and literature in Delhi—Mr. Naem was far from pleased. “You should see the state of books at the Urdu Academy. It’s despicable. They have stored books in sacks. They are in a very bad state” he said angrily. He went on to state that the Lieutenant Governor had recently come to their library and told them that their books were probably too much for them to handle and, hence, it would be best to give them to the government. But Mr. Naem, replying in the negative, asserted that the government was having a hard time managing the books they had at the Urdu Academy itself. Why should they give the government additional books?

Advertisement

Though Urdu is one of the official languages of Delhi, it’s place in the bureaucratic hierarchy seems almost negligible. This is exemplified by the deplorable state of Urdu medium schools in the Walled City. “Urdu medium schools are being closed right, left and center” said Mr. Naem, wiping his forehead with his handkerchief. “Just recently, there were three schools at the backside of Jama Masjid: SKV no.1, SKV no. 2 and Panama Building. One school had approximately 1300-1400 students, the second had 300-350 students and the third had approximately 150 students. Out of these, two are Urdu medium schools. The Government is now planning to merge all three schools. How are students who have studied in different mediums suddenly supposed to merge?”

Advertisement

Another major problem with Urdu medium schools in the capital is a consistent shortage of teachers. In a 2014 Delhi government affidavit, the Supreme Court was informed stated that since most universities in the country do not have Urdu at the graduate level in any discipline, this has led to a mass unavailability of Urdu trained graduate teachers. This lack of teachers, in turn, impacts the quality of education at Urdu medium schools and colleges and hence, perpetuates a vicious cycle culminating in the gradual degradation of the language.

“And what is the point of Urdu medium schools anyway?” asks Mr. Quraishi, the caretaker of Hazrat Shah Waliullah library. “When these students from Urdu medium pass out, they cannot compete with the other mediums. They do not get admission in colleges. They are unable to get placements anywhere. Instead of espousing a deplorable situation like this, why not close all Urdu medium schools? Make them English medium with Urdu as a compulsory language. That would be more lucrative,” says Mr Quraishi in finality.

Advertisement

Irfan Habib expressed a similar opinion. “Why will people learn Urdu if they are receiving no practical benefit from learning the language? Now days, even the students who do speak Urdu are unable to write in Urdu. They write in the Devanagari script instead. At least this is what I have observed in most students at Aligarh Muslim University (AMU)”.

“The loss of the Urdu script means loss of the language; and loss of the language means a massive loss of collective Hindustani culture”, says Habib.

Making my way out of the library, I looked at the boards above each shop, restaurant and building in the lanes of Old Delhi. Most had a board in Hindi, followed by a board in Urdu. When was the last time you noticed an Urdu billboard?