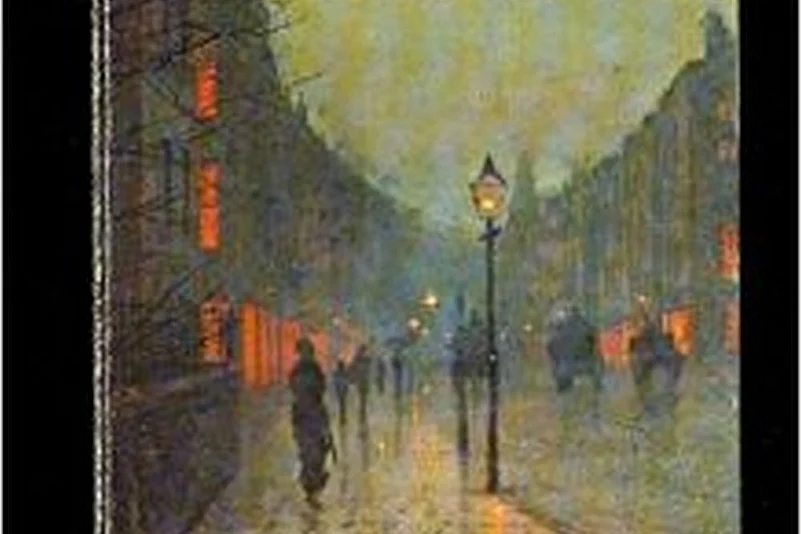

It is a painting of a wide avenue, ringed by mansions, by night. The hard glitter of a full moon beats down on the wide pavements shiny with recent rain. It’s winter; the bare bones of a few trees are testimony to that, as is the muffled shapes hurrying along homewards on a gelid evening. A few hansom cabs have just clattered along, leaving the viewer only a fleeting glimpse of their retreating lamps. In contrast, the embers of life emit a dull, reddish warmth from the houses flanking the road. In the foreground, a figure tentatively makes as if to open her umbrella—a few snowflakes might just have drifted down. Evidently, it’s a Victorian scene, and it sets the mind ablaze.

Advertisement

The painting, or a detail from it, stared back from the cover of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, imparting and emitting, as always, an air of doom-filled mystery. The more one read into Stevenson’s tale, braided in propriety and snarling menace, and the more one looked at the cover, questions flooded the mind. Where are our pedestrians going at this late hour? What dangers, if at all, could they face? What is afoot in those warmly glowing rooms lit by candle and wood? Are they drinking their post-prandial coffee, chatting amiably, or listening to someone on the piano, soaking in Schumann’s Romanticism? Or is there something more sinister happening in there—murderous plots being hatched in whispers, aided by lunacy, vermouth and opium?

Advertisement

The painting in question is View of Heath Street by Night (1882) by John Atkinson Grimshaw, and it hangs in Tate Britain in London. A successful Victorian artist of (perhaps unfairly) middling repute, Grimshaw was born and brought up in Northern England, and his pictures of the 1860s and 1870s—often in and around Leeds and Liverpool—show a growing fascination with maritime subjects like docks, harbours and seascapes. Gradually, with a growing sureness of technique, and in his chosen medium of oil, Grimshaw found his métier—his chosen locales, but lit by the moon. By the 1880s, Grimshaw’s individual romantic vision had led him to paint the pictures by which he is chiefly remembered—town views under the soft, unequally imparted light cast by the moon.

A typical Grimshaw scene is often a leafy, lonely lane skirted by a walled stretch, revealing a brooding mansion beyond, and all of it bathed in an ethereal light. He inevitably deepened the somberness by including a solitary human figure, thereby adding an element of ineffable, uneasy mystery. By 1882, Grimshaw was successful enough to have a studio in London (Heath Street is near Hampstead).

The painting in question reappeared on a book jacket (Father Brown Stories). But this is a darker-hued picture altogether—the moon doesn’t have its noonday dazzle, and the gathering gloom withdraws any glimmer of warmth and cheer from the smouldering windows of the other picture. The effect is grimmer; the few human shapes a confused huddle, one imagines they surely are fleeing an unseen danger.

Advertisement

Is this possibly the second version of the painting that is known to exist? If faithfully reproduced, what was behind Grimshaw’s intention in giving this canvas a further shade of pallor? View of Heath Street by Night can be seen in an innocuous, albeit Romantic, light. Or it can be a setting ripe for the vilest of Victorian crimes, a period crowned by the greatest criminological puzzle of modern times—the 1888 Whitechapel murders.